I accidentally read my way back to church in graduate school. I hadn’t been any kind of practicing Christian since early childhood, but I’d always been a reader, and in those three years, I read more widely and deeply than ever.

I accidentally read my way back to church in graduate school. I hadn’t been any kind of practicing Christian since early childhood, but I’d always been a reader, and in those three years, I read more widely and deeply than ever.

I was in training, an MFA candidate preparing to write the story of me: the coming of age of a Louisiana girl trapped in a fringe group of far-out Christians. It was going to be cool and detached and funny, of course. But something happened. Near the end of my reading list, in my last months of the program, I stopped thinking it was all so funny and started believing.

In my research I’d sought out books of theology and stories of conversion, but in the end, it wasn’t Augustine, Merton or Lewis who convinced me—at least, not in isolation. In classes I was studying film as literature, the New Journalists, short stories and memoirs and criticism, and for the first time in my life, poetry that wasn’t a Shakespearean sonnet.

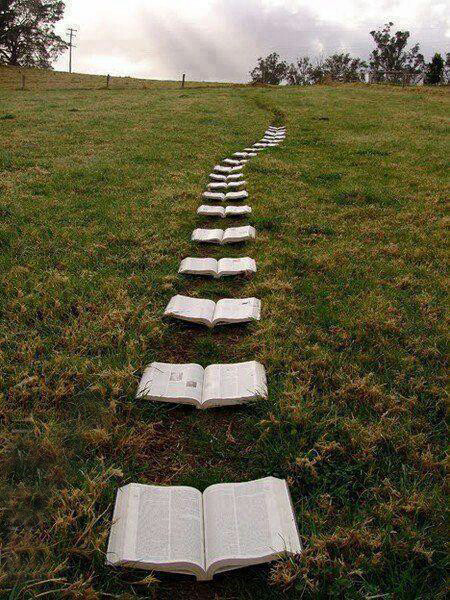

It wasn’t any one book but the collective impression of all that work that sent me back to the pews, convinced there was something vast and eternal governing all, and yet so near and small as to fit in my palm, in a book, in a wafer of bread.

Still, when I feel my faith in that outrageous claim faltering, I feel guilty that it’s reading that restores belief.

Reading is a form of prayer; I know. Divine reading, lectio divina, is a way of communion with God in scripture, the Living Word. But is it wrong that I’ve had more profound experiences of God’s presence reading Anna Karenina, Middlemarch, Kristin Lavransdatter, and my children’s copies of Frog and Toad?

When I feel darkness encroaching and belief seems like folly, I should reach for the Gospels, but without Tolkien and even Colm Toibin they seem like some distant history, and I feel even more removed.

In her memoir Booked: Literature in the Soul of Me, Karen Swallow Prior confesses that she too has worried that she “loved books more than God.”

A lifelong Baptist, she wonders if the fact that she is “more emotionally moved in reading literary works like Great Expectations than in reading dramatic passages in the Bible or in hearing a moving testimony from the pulpit” is “a mark of sin or, at the very least, some great flaw in my spiritual life.”

But the story of Prior’s reading life is a slow discovery that “God who spoke the world into existence with words is, in fact, the source and meaning of all words.” For her, “books were the backwoods path back to God, bramble-filled and broken, yes, but full of truth and wonder.”

Memoirs of reading—shelves of them by Pat Conroy, Anna Quindlen, Azar Nafisi, David Shields—often conclude that books assuage our essential human loneliness, though the may fail in the attempt. C.S. Lewis said we read to know we’re not alone.

But Prior’s claim is more extravagant. For her, reading is an act of conversion, turning her toward the eternal. She writes, “I’ve come to realize that my emotional responses to moving works of literature…are the only way I can bear to respond emotionally to God and his love: indirectly.”

She recalls the story of Moses asking God to see his glory. God answers that man shall not see him and live. In his mercy, he takes Moses to a cleft of a rock and covers him with his hand as his glory passes by. Prior writes: “Literature is like the cleft of a rock that God has taken me to, a place from which I can experience as much of the glory of God as I can endure.”

Prior has seen the back of God in surprising places—not just in John Donne, but in Judy Blume.

Booked opens with an essay on Milton’s Areopagitica, which in Prior’s rendering is as accessible as her chapter on E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web. With Milton, she argues for “promiscuous” reading—the indiscriminate mixing of ideas. There will be no book burning for her (or, as she recalls in an all too recognizable Christian coming-of-age moment, classic rock record burning), no censorship even for the youngest readers.

Prior is unafraid to write that she believes in “truth-with-a-capital-T,” but like Milton, she argues that the best way to expose falsehood is not by suppressing it, but by countering it.

“Truth is stronger than falsehood,” she writes. “Falsehood prevails through the suppression of countering ideas, but truth triumphs in a free and open exchange.”

By way of example, in a later chapter on the “Poetry of Doubt,” she writes, “witnessing the logic of doubt…enabled me to work out, inversely, the logic of my faith.” Sometimes, she proposes, the doubter sees more clearly the demands of faith than the lifelong believer. And the doubter knows intimately what the believer might never contemplate, to her peril: “the reality of existence without God, without faith in God.”

This is a risky book, and Prior writes about literature and faith not just with wit and warmth, but with real courage. In her honesty, she risks alienating Christians with her “promiscuity” and secular humanists with her Christianity.

“We who believe—who want to believe—are asked to believe much, caught as we feel between two ill-fitted worlds,” she writes. And it’s on that lonely ground that her voice is so desperately needed. I don’t know that she set out to be inspirational, but in being so honestly herself—an intellectual Christian who has felt uncomfortable both in church and in the academy—she is.

In one of the most moving chapters, on Hopkins’s poem “Pied Beauty,” she goes right to that uncomfortable tension at the heart of Christianity, joining the poet in praising God for the beauty of all things “counter, original, spare, strange,” for that which radiates only from imperfection and pain.

Recalling characters and events from her childhood, she writes: “Praise him, the poet asks—no, commands—for the awkward things: the fickle, the freckled, the big teeth, the three-legged dogs, the girls that act like boys, and those that are ‘Pretty Plus.’”

This is who drew me back to the Church: the God of the awkward and unseemly, of rocky clefts and backwoods paths; Flannery O’Connor’s Jesus, swinging limb to limb. God coming to me not just in The Word, but in words, in water, bread, and wine.

As Prior writes, “He met me where I was. In Books.”

Jessica Mesman Griffith‘s writing has appeared in many publications, including Image and Elle, and has been noted in Best American Essays. She is the author, with Amy Andrews, of the memoir Love and Salt, A Spiritual Friendship in Letters. She lives in Virginia with her husband and children.