Good Letters welcomes back former blogger Jessica Mesman Griffith, author of the new book Love and Salt: A Spiritual Friendship Shared in Letters.

Good Letters welcomes back former blogger Jessica Mesman Griffith, author of the new book Love and Salt: A Spiritual Friendship Shared in Letters.

“They appear more often now, both of them, and on every visit they seem more impatient with me and with the world,” begins Colm Toibin’s novella, The Testament of Mary. “There is something hungry and rough in them, a brutality boiling in their blood, which I have seen before and can smell as an animal that is being hunted can smell.”

Mary is describing the apostles who hound her as she hides from a vengeful world; they want her to confirm their Easter stories. But she could also be speaking of the angels—angels who brought her the news of her destiny carrying nails and a crown of thorns. It is this image of Mary the hunted that Toibin pursues from the Annunciation to her death.

I’ve never been a fan of Mary the mute, pious doll on the pedestal. It’s neither sinful nor shocking to imagine that the one who was so highly favored might have counted the cost of such honor, or wondered at her own fiat.

The Bible tells us little about Mary, but among the few details it gives us flat out is that she pondered things in her heart, that she wondered about what was happening to her and her son. Mary’s incomplete understanding of her own life story and the meaning of the cross–the engine that drives Toibin’s Testament–is right there in the Gospels.

Toibin’s Mary runs from the foot of the cross. Afterwards, she is so lost in her own despair, her sense of having lost everything and failed her child, that she dismisses the memories of her conception and pregnancy as merely strange and special, something every human mother, lost in the mysteries of her own body, feels. “It does not seem ordinary,” she says. Every pregnant woman has felt that favor, that power and wonder and blessedness.

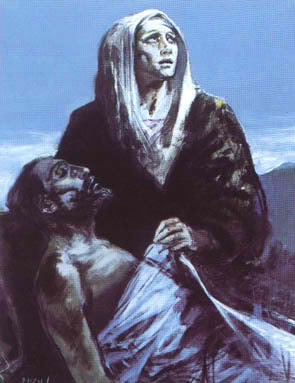

This is not the Queen of Heaven, but the poor in spirit, her suffering so great she is bereft even of the memory of faith. I recognized her at once.

Caryll Houselander, in The Reed of God, also imagined the mother of Christ as a human mother, not the Madonna of the Christmas card. Her Mary is both beautifully human and thoroughly Christian. Her greatest achievement is bringing Christ into the world, which Houselander manages to render—inspirationally—as perfectly ordinary. In this way, she argues, Mary is the only model of sainthood most of us can ever hope to emulate.

Every day, each of us has the same chance to bring Christ to the world through our simplest actions, through saying yes, through our care for our family, through our love for others.

But Houselander’s Mary, however relatable, is not really like us. Or at least, not like me. Her trust in God never wavers.

Toibin imagines Mary without Christianity, a mother who never understands why her son had to suffer. After she watches his torture, she doesn’t care to save her own soul, much less humanity’s. She’d throw away all eternal life for one more golden Sabbath day with her family, for a shy smile from her young son.

This Mary’s love for God and man is dangerously roped to her love of her own family. She is far from the apex of Christianity, or any kind of model for sainthood. She is me.

“It is simple,” she says. “If water can be changed into wine and the dead can be brought back, then I want time pushed back. I want to live again before my son’s death happened, or before he left home…I want to be able to imagine that what happened to him will not come, it will see us and decide—not now, not them. And we will be left in peace to grow old.”

These are the words of an afflicted soul. And yet they are still a prayer. They cry out for redemption. Give me back my life, Lord. How often have I whispered those words to the dark?

Toibin’s Testament is perversely beautiful, and so aware of the nasty truths of the human mother’s heart, that I found it irresistible. Even though he makes the apostles look like a bunch of thugs. Even though his miracle-working Jesus is vain and power-drunk (This Mary is embarrassed by her son’s behavior with his friends—what mother isn’t?). Even though his Mary is bitter and hungry for someone else’s catastrophe to eclipse her own suffering, comforted only by the fertility idol she keeps hidden in a trunk.

I could imagine, faced with the horrible death of those I love, feeling and doing all of these things. Even without such a tragedy, there are dark days and nights when I am, like Toibin’s Mary, without Christianity.

In the end, Mary is hunted only by her own guilt. She dreams of holding her son’s broken body, as the apostles say she did. She longs for death. And yet there is hope. We leave her walking toward her own dream of heaven, a time when all this might not have happened, a place where redemption means that her family was spared.