July 4, 1984. I don’t remember the day, but surely jokes were made back then; the irony of America’s anniversary, celebrating liberty and self-reliance—falling within the year that symbolizes tyranny and oppression.

July 4, 1984. I don’t remember the day, but surely jokes were made back then; the irony of America’s anniversary, celebrating liberty and self-reliance—falling within the year that symbolizes tyranny and oppression.

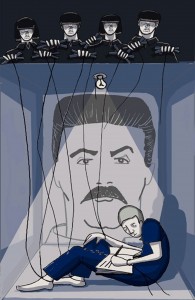

Few are unacquainted with Orwell’s masterwork, 1984, featuring an ever-present state, “Big Brother,” with an eponym that connotes good, wholesome things—family, protection, strength. In the novel, Big Brother ominously moves about life’s foreground, reminding civilians that the system is perpetually awake, watching out “for” them.

Ah, the ambiguity of that preposition. Big Brother takes Christ’s pledge—“I am with you always”—and perverts the meaning to anti-Christical heights.

Here, on the eve of the holiday, the classic has seen a 70% increase in sales (according to the Amazon tracker). The book’s phenomenal rise is easily attributable: the news of law enforcement domestic drones; the ubiquitousness of scanning devices; the secret harvesting of private phone records; the targeting and hacking of journalists; and the use of government agencies, such as the dreaded IRS, as a political screener, strong-arm supplier, and data monitor.

Amazing technologies such as PRISM enable these things to be, along with brave new tools like pre-crime surveillance cameras, biometric databases, and microchip tracking devices.

Of course, it’s a dangerous world now. These things will make us safer, they say. Besides, you can’t desire security and forego its means, we’re told. Even Orwell himself eschewed that kind of pacifist naiveté: “People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.” So it’s wise to remember that potential for misuse is no reason to abandon something entirely.

On the other hand, the potential for misuse is why the most powerful things are that much more dangerous. Strength spoils for deployment, and the greater transparency we have about its scope and motivation, the better.

But when you come to something as prevalent as surveillance, transparency is naturally at odds with efficacy. How can we explain our need for shadowing, thereby checking its misuse, without at the same time tipping our hand, making it useless?

The devil in these details is nuanced, lying at the very heart of man. A friend raised in a communist country explained her wariness of information gathering: “They do it on your behalf, for the common good. But it’s only a matter of time before they use it for something else—not common, not good.”

This is true of even the most benevolent state, and can become the means by which it grows hostile to freedom. It takes a supremely generous view of the sovereign to believe that all its registry-keepers are angels.

“And the power,” my friend continued, “comes by way of the distrust it fosters.” Planting doubt is one of Big Brother’s strongest, deftest tools. There’s a pervasive fear that anyone could be a spy. Big Brother doesn’t even need to be as big as you think he is, because your ignorance as to his true size silences you.

As a result, culture’s fabric weakens—bonds, ties, attachments, are considered irregular. You avoid implicating crowds and keep your mouth shut. Further, no group can stand because all individuals are too wary to form one; nobody inflects even a hint of disgust, let alone a cry of outrage, because such measures risk not only being rebuffed, but also reported—protest is stifled from the outset.

Even to raise these doubts is to risk being labeled a kook, a “black helicopters” guy, a tinfoil-hat- wearing paranoid. Better not to speak than to be misunderstood. How would it look?

And thus we surrender more and more, and begin to watch ourselves as much as we are watched. Our brother is our keeper, we his, and each his own most of all.

Maddeningly, those who do wish us harm seem to creep through the net anyway, despite everything—caught too late, if ever. Because when all are suspect, none stand out. In another time, the recent Boston bombers—who publically avowed their hatred on social media—would’ve been the ones cowering in their holes, not the people.

A black-hearted punk bleeding in a boat would not hold a city of millions hostage. But he did; he will again.

When it comes into its own, the course of state power seems ineluctable. Small things are easier to control, but somehow things just can’t stay small for long. Projects have to get done, so there must always be more people to do them. Then there must be machines to help, and all must be put into records, to keep track. An insurmountable number of machines and papers follow.

Consequently, in addition to the distrust Big Brother promotes, corroding civility, the bureaucracy he requires does more. It transforms those on either side of the cordon. Their responses become stock.

Behind the desk: “My hands are tied.” “We must follow procedures.” “Let me transfer you.” Thus, the person in the box becomes less flexible, less sympathetic, less human.

In front of the desk: “It’s not much to surrender.” “It’s easier this way.” “It’s not worth the hassle.” Thus, the person in the cage becomes less assertive, less dignified, less free.

The newly-empowered would nod at all this. They’d easily qualify it: “Don’t worry. I’m a good guy. Not like them. You can trust me.”

They even have their own set of apologists; the once-condemned measures are all right now, because a “better” set of people are involved. Columnist James Liliks says the excusers offer a heartfelt distinction: “But this ‘Big Brother’ is different,” they say. “He’s mine, and I love him.”

In Tolkein’s trilogy, Frodo, weary of carrying the all-powerful ring, wants to give it to the elf queen Galadriel, whom he knows to be good: “You’d put things to rights….You’d make some folks pay for their dirty work.”

“I would,” Galadriel says, as she rejects it. “That is how it would begin. But it would not stop with that, alas.”

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled, won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.