Guest Post

Note: This post and the one following it have been condensed from an address given by the author.

I’ve been charged today with the task of explaining in some coherent form “why books?”—that is, paper and ink between covers—rather than “books” in some digital format. This is a visceral issue for me and not just because my vocation is the selling of conventional books. It touches me at points of my development as a human being.

The very first book I remember reading is as a four-year-old who could not yet really read, narrating the story as best I could by looking at and interpreting the interspersed illustrations (wood-cut engraving style drawings). It was one of the small bookshelf of books my family owned called The Real Book about the Wild West, by Adolph Regli.

I remember hours lying on our green-carpeted living room floor with this book, in my initial stages of reading. There were of course hours more with this book after I really could read, absorbing the engrossing narratives and unconsciously developing a love for history.

At age seven, in second grade, I happened to check out from the school library George Washington, by the wonderful Norwegian husband and wife author/illustrator team of Edgar and Ingri d’Aulaire (their Abraham Lincoln won the Caldecott in 1939). The book’s combination of unforgettably vivid lithographed color illustrations and unabashed hero-worship and patriotism conveyed in a compelling narrative captivated me.

Fast-forward ten years: I was a high school junior, a cradle Orthodox Christian, caught up in the Jesus Movement of the early 1970s. I had a newfound enthusiasm for the faith, but few intellectual resources with which to undergird it. But I was a reader, and in a footnote I saw a reference to a book by C.S. Lewis called Mere Christianity.

I bought and read Mere Christianity—a cheap, mass-market paperback, green and white, the text of which I boldly underlined in blue ink. This book immeasurably formed my apprehension of the content and extent of Christian faith, excited my imagination, and expanded my comprehension of Christianity’s vastness and wisdom.

I went on to read a good portion of the Lewis corpus. It opened to me worlds of discovery not only in Christian apologetics, but in philosophy, mythology, literary criticism, and memoir. The foundations, as it turned out, of my bookstore.

A year later, I received a book by an Orthodox seminarian who’d been assigned for a summer to our local parish. He quickly became a mentor, and brought my Orthodox roots into closer connection with my Jesus Movement enthusiasms.

It was this book, For the Life of the World, by Alexander Schmemann (silver-covered with a lovely inscription on the title page from the giver), that interpreted all of salvation history through the lens of the liturgy. It laid down a template by which to worship, by which to comprehend worship, by which to aspire to a way of living as a fully human being.

One more way station, ten years later: I was married, working, but laid up for a few weeks with a slipped disc, contentedly lying in bed, enduring the pain with the prescribed Percodan. I read Dom Gregory Dix’s monumental The Shape of the Liturgy, learning that Schmemann’s For the Life of the World meditations converged with the actual history of the liturgy.

Dix’s reading of “every sentence of every Christian author extant from the period of Nicaea”—an astounding claim given the enormous number of books from the period—resulted in a book that permanently enriched my participation in the life of the Church.

I could go on. And I’m certain each of you has a comparable set of books and memories that have indelibly shaped your lives. But I hope you catch my meaning. Books—real, discrete objects—have been my own personal Bethels, “stones” that marked specific epiphanies for me. The object and the experience they mediated are inseparable.

Of course, there is also much to praise about physical books along more pedestrian lines, as marvelous technological objects in themselves. Listen to Robert Darnton, Renaissance scholar and director of the Harvard Library system, from his essay “E-Books and Old Books” in his The Case for Books:

Consider the book. It has extraordinary staying power. Ever since the invention of the codex sometime close to the birth of Christ, it has proven to be a marvelous machine—great for packaging information, convenient to thumb through, comfortable to curl up with, superb for storage, and remarkably resistant to damage. It does not need to be upgraded or downloaded, accessed or booted, plugged into circuits or extracted from webs. Its design makes it a delight to the eye. Its shape makes it a pleasure to hold in the hand. And its handiness has made it the basic tool of learning for thousands of years.

So now we turn from physical books to the digital world in which we have been immersed for the last twenty years or so. The blindingly rapid rise of the Internet is as momentous as Gutenberg’s press and the Industrial Revolution and all the electronic and communications revolutions that followed.

Nothing’s been the same since the Internet arrived: we do business, buy and sell, pay and receive, communicate, organize our schedules, and read differently now. It is changing in breathtaking ways the structure of our whole civilization.

Paleontologist Scott Sampson, in a short reflection in a collection called Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think? sums up the fundamental pro and con of the Internet as the Great Source for Information and the Great Distraction fostering compulsions to stay connected. On the pro side, we must give the Internet its due. It is marvelous and almost magical, multiplying many times the store of knowledge available to anyone in mere moments, facilitating communication beyond our wildest imaginations, and simplifying and accelerating hosts of previously tedious tasks.

Yes, the Internet is a wondrous tool, indeed. The problem is—as is the case with many new technologies—we forget the Net is a tool. Instead of using the tool, the tool begins to use us. We become unconscious of being used, as we are numbed by immersion in a new kind of technological miasma.

To be continued tomorrow.

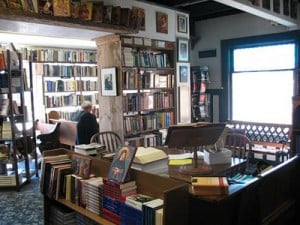

Warren Farha is a lifelong, contented resident of Wichita, Kansas, son of a Lebanese immigrant’s son and a Kansas farm girl. He grew up in his father’s business, until a pivotal moment in 1987 led him into a new vocation of bookstore owner. The bookstore in mind was interdisciplinary featuring classic, perennially important books in literature, theology, history, the arts, and children’s literature, one that also brought his native Orthodox faith into wider contemporary intellectual and cultural conversations. Eighth Day Books is now almost twenty-five years old. Warren shares this endeavor with his beloved wife Chris, three grown children, and a host of past and present friends.