Guest Post

Jen Hinst-White

Continued from yesterday.

Rob goes to bed; I go to my desk and light white candles. Someone I know makes a yearly Lenten project of holding a poetry contest, soliciting translations of psalms from friends. The timing is good; I need a quiet task. Which psalm, then?

Years ago I memorized Psalm 25, and it’s become my favorite ground to walk in the book of Psalms. It’s the one I return to, a beggar’s song of waiting and yearning and aloneness.

Plus—it’s got tricks built in. In Hebrew, this psalm is an acrostic, with the first letter of each line spelling out the Hebrew alphabet. Why the acrostic? Maybe for easy recall when you have no presence of mind. Ache and longing made manageable by mnemonics.

To you, O Lord, I lift up my soul.

O my God, in you I trust;

do not let me be put to shame;

do not let my enemies exult over me.

Do not let those who wait for you be put to shame;

let them be ashamed who are wantonly treacherous.

Make me to know your ways, O Lord;

teach me your paths.

Lead me in your truth, and teach me,

for you are the God of my salvation;

for you I wait all day long.

I muddle around in this for a few hours:

At your hangar door I toss me: a paper plane.

Bring me in from the rain—take me ragged, and keep me

all clear of the suck of the great turbines

Collect me and read me, wee stormied scrap,

and scrap those still scrapping us windward,

O God—

Don’t forget. Fold aright, and write New on my wing—

make limp paper sing—here, then, the wait—

but love’s side-lying

Eight guides all your flights. Right? Remind me. Remind me.

Find me kindly. Not back in my writhing, wriggling loose of my binding—

forgive me, still wild—

God of the Polestar. Pilot Bridegroom. Pied Guider.

He gathers scorched ribbons for the tails of his kites.

If he finds paper squares, he folds cranes for his skies,

and so newsprint shares airspace with stars.

I get stuck at verse nine for an hour or so and I know there are no more words coming tonight, but I can’t leave the desk. I don’t want to go to bed because I don’t want to get up in the morning.

Around one-thirty, Rob comes downstairs looking for me. “I was worried,” he says. Then: “I feel like I’m going to throw up.” He goes and sits on the floor of the bathroom across the hall.

“Do you want me to stay with you?” I rub my face. I can hardly see.

“Get some sleep,” he says.

When I was twelve years old, I used to go once a week to the middle school guidance counselor’s office. Her office was the size of a large closet, and I liked it—cozy. Wood paneling, no windows, carpet like that of a cat’s scratching post. Nature posters. The counselor was plump and bronzy blond.

All my hours in that room have layered themselves into one blurry hour, as if time stopped whenever I walked through her door. I don’t remember anything I said, or she said. Except for one conversation. I remember I said: “I wish they would just decide yes or no.”

My parents couldn’t make up their minds about whether to stay together. When I was nine, they sat us down in their bedroom, my brother and me, and said they were getting divorced.

Then, some months later, they sat us down at a Chinese restaurant and said they were going to stay married, after all.

Then my father started taking a lot of business trips to California, and sometimes a woman would call.

Then my parents planned a family vacation for Easter break. We drove down the East Coast through Maryland, Virginia, Georgia. They held it together until Disney World, I think, and then an argument boiled over in the middle of a souvenir shop. My mother walked out, my father stood there; I froze, not knowing if I should stay with him or follow her.

“You’d rather they get divorced than keep you wondering anymore,” the counselor said.

“Yes,” I said.

I drive to work on my few hours’ sleep, feeling hollow. Am I a chrysalis or a catacomb? At six weeks, there should be a heartbeat.

I pray I will miscarry quickly.

Then I am quiet for a while, because my own prayer strikes me as strange. I’d choose death over possibility? Just to avoid the waiting?

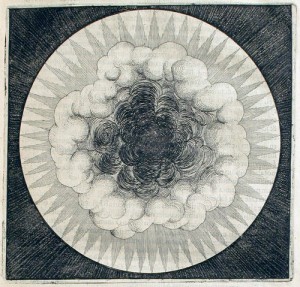

“Thin places” are geographical. They are spiritual doorways in physical space. But they have a chronological cousin: liminal spaces. Liminal spaces are waiting times, doorway times—thin places measured in days, not square miles. In an essay called “Grieving as Sacred Space,” written after 9/11, Richard Rohr describes them in this way:

“Limina” is the Latin word for threshold, the space betwixt and between. Liminal space, therefore, is a unique spiritual position where human beings hate to be but where the biblical God is always leading them…. It is no fun. Think of Israel in the desert, Joseph in the pit, Jonah in the belly, the three Marys tending the tomb.

If you are not trained in how to hold anxiety, how to live with ambiguity, how to entrust and wait—you will run—or more likely, you will “explain”…anything to flee from this terrible cloud of unknowing.

“I want to give you the benefit of the doubt,” the doctor said to me.

Jen Hinst-White recently finished her first novel, Inkliings, the story of an aspiring female tattooist in the early 1980s. Her writing has been published (or is forthcoming) in The Common, Big Fiction, Cactus Heart, HoldADoor.com and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Her website is jenhinstwhite.com.

This paraphrase of Psalm 25 was first published as the winning poem in the 2013 Works and Days Psalm Translation Contest (matthewlandrum.com). Grateful acknowledgment to Matthew Landrum for permission to republish it as part of this essay.