Reflections on the Jewish High Holidays 5774.

Reflections on the Jewish High Holidays 5774.

On the second day of Rosh Hashanah, I checked my “Good Letters” post of the day before, “Today’s Child Sacrifice,” to see how my numbers were looking.

(Yes, I check—obsessively. Thank you, kind readers, who share my posts with others, you whose approval I seek with every refresh. Practice opportunity: restraint.)

I found this: a new comment! I scrolled down.

From Concerned Citizen: “40 million children have been killed since Roe vs. Wade, but the author is silent about this type of child sacrifice. Why? Because all Jews are Obama-loving liberals, and they are glad the goy children are being killed.”

You probably didn’t get to see Concerned Citizen’s comment. I read it on my iPhone, in my driveway, early afternoon, just after returning from services where I delivered the d’var Torah, an expanded version of the very post on which this “concerned citizen” commented while I was at synagogue.

My first personal experience of anti-Semitism! But what if it isn’t, what if it isn’t anti-Semitic? My middle name: doubt. For a moment, I hesitated. Then I wrote to Greg Wolfe (“Good Letters” editor in chief). A few minutes later: vanished! Silenced! (Thank you, Greg.)

You probably don’t hear that silence, you who didn’t get to read the comment posted briefly, but I do.

Concerned Citizen, too, heard a silence, a silence in my essay that I didn’t hear. And, giving voice to the voiceless, Concerned Citizen roared, an ancient, malicious roar: Jews kill Christian children, Jews killed Christ.

They tumbled from the Ark.

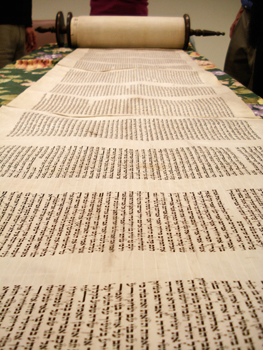

First, there was a muffled gasp. Then one or two congregants began to rise to their feet, as customarily we rise when the ark is open and stand while the Torah—weighing as much as a two-year-old, weighing as much as our martyrs throughout the ages, weighing more than God— is cradled in a congregant’s arms. In a moment, we were all on our feet. Stunned, silent, we watched the prayer leaders carefully, lovingly lift the Torahs and return them securely, we prayed, to the ark.

The Yom Kippur evening service had barely begun. A highlight for many, its opening act, the Kol Nidre, the prayer releasing us from all vows made from last Yom Kippur to this one, releasing us, as well, from all vows we will make between this Yom Kippur and the next one, had been beautifully chanted by my favorite of the guest cantors we’ve hired for the high holidays over the years I’ve belonged to Congregation Beth Israel.

As is our tradition, during each of the three repetitions of Kol Nidre, past presidents and the current president of the congregation received the honor of holding our Torahs. After the completion of Kol Nidre, the scrolls were returned to the ark, the white curtain drawn closed, the doors of the ark swung shut.

Just as we began to settle in for a long night of solemn prayer, they tumbled, two Torah scrolls, from the ark.

Shaken by what happened, I did not know how to pray.

Was this a sign, an omen, the falling of the Torahs? Falling on the holiest night of the year, the beginning of the holy day when, according to tradition, the fate of every Jew for the coming year is signed and sealed: who will thrive, who will suffer, who will live and who, “by high ordeal” or “common trial” ( as sings Leonard Cohen) will die.

Was it, this unfortunate accident, because of me, because of my sins? Will something bad happen, God forbid, to one of my children this year?

Helpless: if only I could rewind the last few minutes of the night, but I could no more magically reverse time and save the Torah scrolls, save us all from their falling, than I can protect my loved ones from suffering, from harm.

Helpless, and vulnerable to magical thinking.

Vulnerable: “Susceptible of receiving wounds or physical injury; open to attack or injury of a non-physical nature” (Oxford English Dictionary).

The editors of “Good Letters,” once alerted to the presence of the hateful comment in response to my Rosh Hashanah post, removed it. But they know as well as I that this particular manifestation of hatred, in the form of anti-Semitism, seems invincible. Every Jew, everywhere, at all times is vulnerable. Consequently, we are vigilant, acting prudently to defend and protect ourselves from those who wish us harm.

The Torah, too, everywhere and at all times, is vulnerable. And when I heard the wooden staves knocking open the doors of the ark, and when I heard the thud of the Torah scrolls striking the carpeted floor, my heart darkened and cracked, releasing its blue-black ink. If you were to have looked, you could have probably seen the stain just under my skin.

Cracked open, my heart was, and it hurt. I can’t speak for the other congregants. All I know is that I stood with them, the ark of my heart open to receive a fallen Torah, returned to its proper place. That’s vulnerability. As is living with the knowledge that even when it is returned, as it was that night, it might fall again.

Even when I promise, I vow, as I might have done that night, to carry it carefully, lovingly through to the closing of the heavenly gates, the final blast of the shofar signaling the end of Yom Kippur—through to, at last, the bagels and kugel and tea—even when I resolve to carry it even now, days later, I know it might be torn from its place by human hands or called to earth by laws of nature or tipped over by some finally unknowable force and I might be helpless to prevent it, helpless to do anything other than witness and adjust and renew my commitment to live by its spirit and words.

Richard Chess is the author of three books of poetry, Tekiah, Chair in the Desert, and Third Temple. Poems of his have appeared in Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of IMAGE, and Best Spiritual Writing 2005. He is the Roy Carroll Professor of Honors Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. He is also the director of UNC Asheville’s Center for Jewish Studies.