As the smoke—black at first, but slowly giving way to white—escaped into the sky above the Sistine Chapel, I was driving somewhere between D.C. and Richmond. There would be a wait, the NPR commentators said, while the newly elected pontiff was taken into Saint Peter’s and prepared for his grand debut on the balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square, the Loggia of the Blessings.

As the smoke—black at first, but slowly giving way to white—escaped into the sky above the Sistine Chapel, I was driving somewhere between D.C. and Richmond. There would be a wait, the NPR commentators said, while the newly elected pontiff was taken into Saint Peter’s and prepared for his grand debut on the balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square, the Loggia of the Blessings.

So I waited—I had nothing better to do—and listened as they pattered on about what might be going on behind the grand façade of St. Peter’s: Would the new pontiff be African?—unlikely. Would he be American?—definitely not. Conservative?—of course.

No one anticipated, not the devout, and especially not the critics and cynics what the Church has earned for Herself: that this new pope would take the name Francis, and that his voice would sound so radical and new. It shouldn’t. He’s only speaking the Gospel, saying what other popes have said before him, but from his mouth and combined with his actions, it no longer seems like some distant ideal.

I’ve remained Catholic, though there is so much to be disappointed in and angry about, from sex scandals to liturgical music that’ll make your ears bleed, in large part because I want to be a part of the same church as St. Francis of Assisi. But I’ve long wondered if the average American parish would welcome the poor man from Assisi, or if my conception of him is pure bohemian romance.

I know I’m not alone in romanticizing Francis—even the angriest lapsed Catholic and the most secular of humanists will proudly host a Francis birdbath in his garden. Our new pope has wisely chosen the name of the last beloved emissary of the Catholic Church to the masses.

When we moved to Virginia, I was delighted to find that the Catholic church nearest us was named for St. Francis, though we soon began to refer to it as Our Lady of the Covered Dish, because of the regular potluck dinners and wine and cheese socials held after mass.

The parishioners were, for the most part, older and very generous. The parish gave a lot of money to charity and participated in service projects. Our priest, who we shared with three other rural parishes, also had an active prison ministry. Still, something didn’t feel right to me. Eventually I realized it was that I never laid eyes on the people we helped. They remained safely invisible.

We were coming from South Bend, where we went to First Friday masses at the Catholic Worker house, one of three places in the city that housed the homeless and indigent. After Mass we sat and talked with the “guests” over bowls of soup and slices of homemade bread. They held our infant daughter.

Something felt wrong at my new job too. I’d just published a book that dealt with issues of peace and justice, but I was teaching at a private women’s liberal arts college known for its equestrian facilities and finishing school past—it was an unwritten rule that all students own a strand of pearls. After teaching at Notre Dame—wealthy and immaculately manicured, yes, but a hub of social justice-minded Catholicism with a strong culture of student service—I was annoyed by the fear and suspicion of the Other on campus.

In our first weeks there a professor’s husband, wearing a bandana and dirty work pants on his way from the community garden, was stopped by campus safety on suspicion of being vagrant. When I encouraged my journalism class to write about injustices on campus, they were reluctant to stir up controversy or to print bad press about the college.

As someone who has always had, for better or worse, a lot of self-confidence, a can-do, no-quit attitude toward almost everything, and a healthy constitution, I have never backed down from a challenge. I remember my parents insisting that whatever it was that I chose to do (“garbage man” was my mom’s favorite example), I should strive to be the best at it that I could possibly be. I was determined to find a way to excel at my job, to combine these two aspects of my life, the tweedy writer-professor and the social-justice Catholic. I would crusade for what I knew was right and just.

But it was to be so much harder on my soul than I imagined. Over the six years I taught there, I began to lose my patience and my temper. I blamed the apathy I encountered in the classroom every day. But the problem wasn’t the students; it was me. I was crusading, but for some invisible set of values that was beginning to seem impossible and romantic even to me. There was no leading by example and no serving with joy in my heart, only contempt.

That is what I regret now, that when I think back, I know, especially in the end, that I couldn’t have appeared joyful to them. If I’d set out to emulate Francis, I failed in the most fundamental way.

As I drove through Virginia listening to the radio, I fought off the creeping cynicism that a new pope in Rome would make any difference in my life, but when the new Pope Francis finally came out on to the loggia that day, he was introduced by a fellow cardinal who announced to the thousands gathered in St. Peter’s Square and the millions listening around the world via the radio and internet that anyone hearing this broadcast would be blessed.

My heart broke open and I started to cry.

To be continued tomorrow.

David Griffith is the author of A Good War is Hard to Find: The Art of Violence in America (Soft Skull). He is the Director of Creative Writing at Interlochen Center for the Arts in Michigan where he lives with his wife, fellow Good Letters contributor Jessica Mesman Griffith, and children, Charlotte and Alexander. His essays and reviews have appeared in Image, Utne Reader, The Normal School and online at killingthebuddha.com. He blogs at Pyramid Scheme.

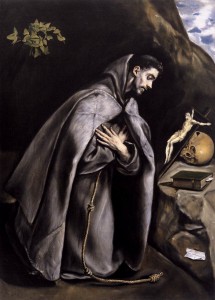

Art Pictured: St Francis Meditating by el Greco (c. 1595)