In our current Western culture, we think we have control of time. With our watches and clocks we regulate our lives: meetings set at a certain hour (see you at noon!), alarms wake us at the set minute, we schedule bedtimes and lunch breaks. In the U.S. we even change the time by one hour twice a year. What hubris.

In our current Western culture, we think we have control of time. With our watches and clocks we regulate our lives: meetings set at a certain hour (see you at noon!), alarms wake us at the set minute, we schedule bedtimes and lunch breaks. In the U.S. we even change the time by one hour twice a year. What hubris.

Not so in other cultures. Living in New Mexico years ago, I remember going to a Pueblo tribe’s festival. We Anglos arrived and waited impatiently as our precious time passed. When would the event get started? “When the time is right,” a woman of the tribe told us.

And the end of Ramadan for Muslims everywhere: it’s determined by a sighting of the new moon. I ask my Muslim friends who have invited me to share their breaking of the Ramadan fast “what time will it be?”…

Time’s flux. Though we Westerners try with all our might to pin it down, the effort is fruitless. Or, as the contemporary Mexican poet Javiar Sicilia puts it in “The Track in the Wilderness”:

time is not time

but the vast emptiness from which things flow.

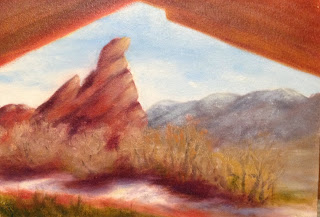

Sicilia’s poem, in the current issue of Image (#78), is a profound meditation on our perceptions of time. The poem begins with the speaker and a female companion walking down a beach along the “track of time,” toward a huge red rock that later in the poem becomes a cave and then the dark void from which issues “the resounding language of God.

we saw, under that red rock,

time stopping in the song of the sea and its recurring voice,

between the ruach of Yahweh and the hour of this now,

before the travelers’ breakfast,

the hollow words,

the yellow fog in the window

and the din of a thousand worlds ending;

before yes and no,

before a thousand I-love-you’s

and eating a bit of bread with our coffee,

in that gaping hollow in the void

under this red rock, you and I saw time stop.

The entire 240-line poem does, in its way, make time stop. And it does so by interweaving recurrent images: from this scene, from Dante, from T.S. Eliot, from the gospel episode of Jesus on the road to Emmaus.

But what can it mean to “stop time”? In the poem, it comes to mean, I’d say, an opening up of time into the eternal—by the discovery of the Risen Christ (called only “the third one”) walking along the beach with the speaker and his companion. Time as we ordinarily experience it, rushing onward toward only our deaths, is “stopped” when we notice that the “gaping hollow in the void” is God.

Reading Sicilia’s poem has led me to experiment with perceptions of time. Looking up at the sky through tree branches that were filled with green, then a few months later orange, then bare, then snow-covered, I consciously think: for me, this is a moment; but since God is in this moment, it is somehow eternal. Or, practicing deep yoga breaths, I think: this is the Holy Spirit breathing in me.

Or I ponder the wonderful passage from Simone Weil which Sicilia takes as his poem’s epigraph, a passage where she says that “what we call time” is God’s “waiting.” I remember her elaborating elsewhere: God waits in eternity for us to merely turn our eyes toward him.

Could I ever be so free of self, and so free of self-imposed scheduling, that I could truly turn my eyes toward God?

Each morning for twenty minutes I give it a try. I sit and pray to let all in me that’s not God drop away. And then within two minutes I’m daydreaming. Do I have enough potatoes to make that soup recipe for supper?

But maybe turning my eyes toward God won’t happen during that intentional effort each morning. Maybe it could happen if I give an instinctive “yes” to a request from someone I don’t like much, a request that will inconvenience me. That might be an emptying of self such as Sicilia’s poem evokes:

Impoverish yourself, Daughter of Man,

until you are emptiness,

for what is created then, to your astonishment,

is the empty space the god makes, retreating,

for what you see on Christmas Day

is the muteness of the god in his word;

what you see at Easter-time

is the empty space the god makes, renouncing,

and what you are not is the only thing you are

and where you are not, only there can life be.

This is not an easy, feel-good religious practice that Sicilia, with Weil, is envisioning. There’s no wiggle room in that “what you are not is the only thing you are.”

God is waiting for me to be what I (my treasured self-constructed self) am not. And this waiting is “what we call time.”

The phone rings. It’s a friend, asking to have lunch together on Thursday. I look at my calendar. “Oh dear, I don’t have time that day.”

“I” don’t “have time”? Time isn’t mine, so I never “have” it. God, in his waiting, cringes.