Consider the coffee table. It’s a venerable and eminently practical piece of furniture. Most of us have at least one. It’s a great place to put centerpieces, books, even literary journals. Some of us may put our coffee mugs on it from time to time.

Consider the coffee table. It’s a venerable and eminently practical piece of furniture. Most of us have at least one. It’s a great place to put centerpieces, books, even literary journals. Some of us may put our coffee mugs on it from time to time.

But have you ever noticed how often these days that coffee tables aren’t coffee tables? Walker Percy did. In Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Guide, Percy noted that a home and garden magazine had listed fifty ways to make coffee tables…out of something else. The examples cited included: a polished Cypress stump, a lobster trap, a large spool for telephone cable, and a stone morgue table, with the runnel for blood used as an ash tray.

To Percy, these alternative coffee tables were not merely examples of human ingenuity, but evidence that the modern self, over-stimulated but at the same time increasingly numb and inattentive, was prone to negating the ordinary objects in front of it. So the modern self finds itself needing to recover the meaning of a thing through increasingly outlandish means.

In short, according to Percy, we need a lobster pot to restore our perception of “coffee table.”

It isn’t necessary to pursue Percy’s fascinating analysis of the modern self to recognize that he’s also touching on a fundamental human problem: things that once meant something to us have a way of disappearing, losing their ability to signify what they are or what they represent.

The reasons for this are legion. Sometimes it’s just too much repetition, over-use, poor imitation. Sometimes the historical and cultural conditions that generated an object are no longer present, and thus it no longer speaks to us with the force and freshness it did to its contemporaries. Perhaps what the prior generation saw was only part of the truth and new circumstances push the artist to find another facet that needs to be seen and encountered.

When things become opaque, we need a form of newness to restore their translucency so that we can see once again the truth they point to. To be sure, this need for newness can become a fetish for novelty or innovation. As most artists or craftsmen or even engineers will tell you, the new, like happiness, is not something you pursue directly.

For example, an artist works at the nexus where past and present meet—tradition and the individual talent. That place—where the artist’s materials, what’s gone before, and the peculiar circumstances of the present all come together—is where something new can emerge. Not, perhaps, “original” (in the fetishized, romantic sense), but genuinely “new.”

As a young man working under the influence of Neo-Platonism, Michelangelo created the famous, highly-revered Pietà in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Michelangelo gave the figures of Christ and Mary an ideal beauty—the outward representing the inward. The equilateral triangle of this sculpture also radiates a sense of stability and serenity. Every polished section of the surface pays homage to perfection.

Decades later, Michelangelo would repudiate his earlier work, censuring its sensuality. Under the influence of the Counter-Reformation, his faith deepened and took on a more intense, expressive form.

His Deposition, sometimes known as the Florence Pietà, is vertical, not horizontal. Begun nearly half a century after the Vatican Pietà—the sheer weight of Christ’s dead body and his awkwardly jutting leg make for a more agitated, unstable effect. But at the same time, as Christ’s head rests momentarily against that of his mother, the grief and poignancy of the work are heightened.

Michelangelo took a hammer to the Florentine Pietà out of frustration with its apparent failure. So he would try again with a piece that he worked on until his death: the unfinished Rondanini Pietà. Here, too, we have a vertical sculpture, inherently unstable, but reduced again to the figures of Christ and Mary. Now Mary is behind her son, seeming to literally bear his weight. Their intimacy in death the mirror image of their intimacy in birth.

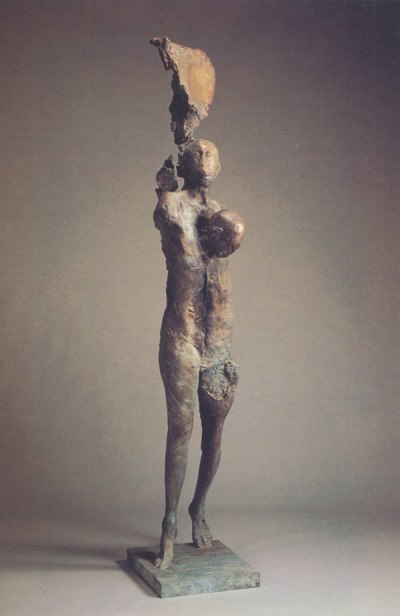

Now move forward 500 years. The Bay Area sculptor Stephen de Staebler, no stranger to suffering and loss, spent years pondering Michelangelo’s three pietas, sensing the movement from horizontal to vertical, from serenity to anguish, from formality to intimacy.

Now move forward 500 years. The Bay Area sculptor Stephen de Staebler, no stranger to suffering and loss, spent years pondering Michelangelo’s three pietas, sensing the movement from horizontal to vertical, from serenity to anguish, from formality to intimacy.

De Staebler was moved by Michelangelo to go one step further. In his bronze Pietà, Christ and Mary have merged: Christ’s head emerges from Mary’s breast—birth and death coming together. The legs don’t quite match; the stance feels unstable. Mary’s face is a primitive mask, the peasant woman who has endured much and lost much.

De Staebler was moved by Michelangelo to go one step further. In his bronze Pietà, Christ and Mary have merged: Christ’s head emerges from Mary’s breast—birth and death coming together. The legs don’t quite match; the stance feels unstable. Mary’s face is a primitive mask, the peasant woman who has endured much and lost much.

Each of these four pietàs possess a newness that renews our understanding of the Gospel story in all its richness.

Making it new is a discipline that each of us needs to practice, lest we become blind to the truth of the world. Artists help to do that for the stories and images that are in danger of losing their meaning.

Religion, like everything else, needs constant renewal, lest already elusive truths and experiences either disappear or harden into falsehood.

Nearly twenty-five years ago, Stephen De Staebler’s Pietà appeared on the cover of our second issue of Image. Since then, Image has dedicated itself to furthering this work of making it new in the realm where art, faith, and mystery meet.

It’s an inherently risky business, subject to failure. At times it may feel like something you want to take a hammer to. But the alternative is stagnation.

By definition, making it new is also an ongoing task—one that I hope you will share with us in the years to come.

Gregory Wolfe is the founder and editor of Image.

You can make your tax-deductible gift to our “Making It New” campaign here.