This is a story that is more about what I don’t know than what I do.

This is a story that is more about what I don’t know than what I do.

On the Friday night after Thanksgiving, the third night of Chanukah, my neighbor Rose, next-door neighbor to St. Linda, died. Just three or four days before, her adult son who lived with her—retirement age himself—had called to tell us that his elderly mother, whom we had seen less and less in the last month or two, was in home hospice care and did not have long to live.

Could I come see her? I asked, for she had been a wonderful neighbor and I had loved her greatly.

His simple reply: She doesn’t want any visitors.

So instead, I kept calling to check in on her, the last time the night of Thanksgiving from my sister’s house, the high shimmer of candles at the edge of my eyes, straining to hear over the sound of wine-soaked merriment. She’s okay, he said. Please let me know if there is anything I can do, I replied.

He called Saturday morning to say that Rose had died. She was ninety-three years old.

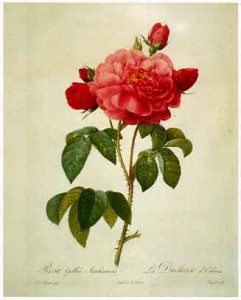

“Rose” was not her name, but my neighbor was greatly reticent and would not have wanted, I imagine, her real name to appear in print. The name Rose is the closest analogue I can think of to the delicate, flowery German name that she actually had.

Even now, I pull this name out of my mind periodically, say it to myself like a sweet in the mouth, and wish for a moment, however illogically, that we could have given it to my daughter. Perhaps, I now think, I can talk Anna Maria into using it for one of her dolls, or her own daughter someday—for the name, and the memory of “Rose” herself, who only had sons and grandsons, are too beautiful to be forever lost.

And yet so much is lost, so many pieces of her story that it was not granted for me—or most others, I’d wager—to know. She was German, she was Jewish, a heritage with its inescapable implications. A wall in her dining room was hung with black-and-white photographs of staid relatives with grave expressions, but she was not interested in talking about who they were, or where they were from.

Somehow, she had married her husband who worked for the State Department, gotten out of Europe, and come to the United States and settled down in 1947 in the red brick colonial house she lived in continuously until just weeks ago. She had a sister who lived in Paris, whom she knew she would never see again, and that was the only sibling she ever mentioned.

She lived modestly, but immaculately. Her kitchen, tiny and unrenovated, decorated in faded and dreary 40s colors, was cleaner than mine could ever hope to be. In the early years we lived here, she would walk out of the house on a summer afternoon in a crisp cotton skirt and sandals, her lips touched with bright red lipstick. In the afternoons, she would ritually nap on the chaise lounge on the sun-porch at the back of the house, her legs stretched out luxuriantly. (I learned the hard way to curb how I spoke to my children in the backyard, for we knew that she was always paying attention to what was going on around her.)

She woke every day around three o’clock in the morning, when my husband was typically getting ready for work, and I learned to mark the day by the appearance of her yellow living room light burning in the dark.

But she could also fix an imperious stare on you if she felt you were falling down on caring for your house or yard, and many times over the years she’d call—Just to let you know—that she thought our trees needed trimming because she was afraid a branch would fall and hit the power line.

I took over a bouquet of flowers to her on Rosh Hashanah once, which she loved, but exclaimed, “You know, I’m not very religious.” She complained once about having to go to the Bar Mitzvah in Baltimore of her Orthodox Jewish cousins, “who fought all the time.” But another time she also mentioned to me the quiet sharing of a new year’s honey cake with her son—simply and at home, the way she did everything.

When I was blowsily and unexpectedly pregnant at forty, she appeared one day at the door with a handmade baby blanket, with bright images from nursery rhymes carefully cross-stitched on the cotton. (She was eighty-nine then; think of those arthritic fingers!) After Anna Maria was born, she appeared at the door with a dish of rich, hot chicken salad that I ate over the sink in a nursing-starved mania. She later gave me the recipe, carefully printed in pencil on a lined notepad page.

Everything was immanent for her; she would not yield up her secrets. She would not “tell me about her life,” or let me record her memories, and I felt bad even asking. (“Writers are always trying to sell somebody out,” writes Joan Didion.)

She resolutely refused to join the great self-revelatory, confessional zeitgeist that marks our time, the first-person narrative avalanche of Facebook and StoryCorps right on down to my own blog posts on “Good Letters.”

The confessional impulse, despite its religious literary origins with Augustine, is today, I think, largely the effort of a secular society seeking to find its own godless religion: We all become our own religious texts.

Rose would not play that game. The canon was closed. Instead there was the sunlit morning, the goings-on of neighbors through the parted blinds, and the gift of her German plum tart that could only be made in the briefest summer season (the recipe for which I found, as part of the Lost Recipes series, on nothing less than NPR.)

L’Shana Tova. May it be sweet for you, now and always, Rose.

A native of Yazoo City, Mississippi, Caroline Langston is a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She is a widely published writer and essayist, a winner of the Pushcart Prize, and a commentator for NPR’s “All Things Considered.”