Continued from yesterday.

Continued from yesterday.

For most of the fall after we moved to Northern Michigan, I was sick with a bad respiratory infection that turned out to be bacterial bronchitis. The doctor sent me home with an antibiotic and a prescription for an SSRI—an antidepressant. She said she was concerned about the coming dark months and the cold of my first northern winter and my compromised immune system. The stress of the move, she said, could be why I can’t seem to get well. She’d looked over my family history.

So she prescribed the pills even though I didn’t tell her I was depressed, and I definitely didn’t mention that I’d been haunting the grounds of the old insane asylum brooding over my schizophrenic uncle. Or that I’d bought a pack of Venus disposable razors at Meijer the week before—because shaving my legs was the only sort of self-help plan I’d been able to launch that day—and now I couldn’t get that Bananarama song out of my head.

I didn’t tell her how much I hated the idea of that song being lodged deeply in my subconscious, not just because it’s so awful, but because it’s the sort of thing that would have tormented my uncle to the point of violence. We couldn’t turn on the radio in his presence. When it was really bad, he wasn’t allowed books either.

I didn’t want to take those little pink pills. I didn’t want to need them to get well. I wanted the cod liver oil and brisk walks and hot toddies and prayers to work. I reread Sara Zarr’s Prozac vs. Jesus and wondered why taking medication felt like a failure, like quitting—artistically and spiritually. I should be stronger. I should be able to pull myself out of this. I should pray more, write more, exercise more, take vitamins and think good thoughts.

And then I remember my uncle, who lost his young family—we never met his wife and are unsure but there might have been a baby too—and spent his days on the porch with no book. I opened the bottle.

I took the little pills every day and as the doctor promised, I got well. I don’t think I realized how sick I really was.

I sit here in the dead of the hardest winter Northern Michigan has endured in years, feeling pretty good, mostly free from obsessive thoughts and inane songs from my childhood. I sleep at night instead of tossing and turning, coughing, and dreaming of Virginia. I read Norse myths and walk in the snow and feel like a Viking.

I still cry easily—motherhood made me soft and no drug will erase that—but I feel, as my doctor described, the floor beneath my feet. If I sink a bit in the day something catches me before I tumble into the abyss. I can look at something beautiful without crying. I can put my uncle’s papers back in the cedar chest.

The mornings are easier now that I’m well. My kids are up early for school. I drop them off with time to spare and drive to the asylum to snowshoe. It’s a fair day, and I photograph the striking image of the terracotta colored spires against the bright blue sky. In the snow, it looks like a fairy tale.

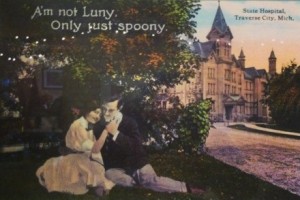

The Commons isn’t ashamed of its history as an asylum. And though I’m a little shocked, I’m glad all the same to find a reproduction of a vintage postcard in the hallway, a reminder of a different age: “I’m not loony, only just spoony,” reads the caption. The image is a young man holding his sweetheart on the lawn of Building 50.

But my favorite, discovered in a local history book, shows a guy with a giddy, panicked expression sneaking off the grounds with his suitcase, and the caption, “I’m now at liberty to write.”

Jessica Mesman Griffith‘s writing has appeared in many publications, including Image and Elle, and has been noted in Best American Essays. She is the author, with Amy Andrews, of the memoir Love and Salt, A Spiritual Friendship in Letters. She lives in Michigan with her husband and children.