When Marie-Henri Beyle visited Florence, that city named for its place among waters, he thought the art he came across might kill him. Visiting the Basilica Santa Croce in 1817, he wrote that he “was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart…the wellspring of life was dried up within me. I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.”

When Marie-Henri Beyle visited Florence, that city named for its place among waters, he thought the art he came across might kill him. Visiting the Basilica Santa Croce in 1817, he wrote that he “was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart…the wellspring of life was dried up within me. I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.”

When I first heard of what is now called Stendhal’s syndrome (Beyle’s penname was Stendhal), I was overcome myself, with envy. I was studying English literature and art history in college, but I had never been so undone by my subjects.

The summer after learning about Stendhal’s syndrome, I bought a collegiate Eurail pass, starting my travels in Italy. I went to Rome and Florence. I saw the Sistine Chapel, and I thought it was beautiful, but other than slight nausea from the summer heat and dehydration, I had no physical reaction. I considered my failure to experience this ecstasy a deficiency; a true art lover, surely, could have brought herself to such a place with the appropriate knowledge and awe.

I left my art history on the sun-soaked campus in North Carolina when I joined the Army. The art I carried with me was music, from one choir to the next in North Carolina, Bosnia, Korea, Texas, and finally Seattle.

Music transported me out of the southern heat, out of experiences that alternately stifled and exhilarated me. It gave me a living pulse of connection in the most remote places I was stationed. I plunged into it as a place I could be subsumed, bathed in beauty.

This sensory saturation was selfish, mostly, not dissimilar from the pleasure I took in the literature and art I studied in college. I used it for my own ends—I still do. I didn’t understand the risk of opening. Palpitations of the heart would be nothing.

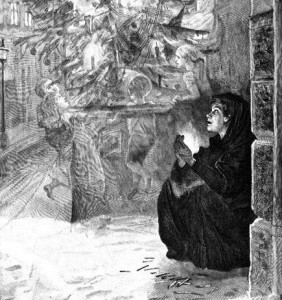

More than two decades after my failure in Italy, I sat in the north apse of Seattle’s St. James cathedral and sobbed listening to David Lang’s Little Match Girl. Stendhal syndrome relates to what is seen, not heard, but my tears came for the sounds curling into the cupola and the swirling torrent of words.

It wasn’t the music that did it, I thought. It was the words. It couldn’t have been the words—just a fairy tale! But then, no, the music. The woman next to me handed me the piece of fabric she had folded behind her own score. She averted her eyes. I wiped my eyes, my nose, my eyes. Again.

We were part of a choir singing a concert titled Passio, a setting of Hopkins poems by Britten and a Russian mass. Smaller ensembles performed additional selections, most notably Lang’s Pulitzer Prize winning piece. It’s a piece that defies categorization, a small mixed choir accompanied at intervals by only a few unusual percussion pieces: bells, a drum.

The piece alternates the telling of the devastating fairy tale by Hans Christian Anderson with paraphrased excerpts from the St. Matthew’s Passion choruses. I listened to it once at dress rehearsal, again at our first concert, and the second concert did me in.

Lang looked to juxtapose the suffering of Jesus with the suffering of a little girl, and perhaps that is the key to the universality of the piece. I listened and thought of that girl, and imagined my son as that girl, and knew, suddenly and with brutal clarity, that the little match girl was everywhere.

At the moment I listened she struck her matches against the walls of a mosque on the streets of Syria, of the Ukraine, of the Sudan, of the Congo, of Seattle. Our son’s babysitter, who used to work for CPS, told me when I came home from the concert she had once picked up a three-year-old girl in a four day old diaper, high on the meth she’d licked off her hands from surfaces in the apartment where a parent had abandoned her in California. They are everywhere, our babysitter said. You just don’t hear the stories.

The matches are flaming, and going out.

This is what so many years of art will do to you, so many years of music. It’s preparation to open your heart, even when you think it’s all been selfish. You sit in the dark church saying in horror, over and over, “Lord, have mercy,” because there is no way to forgive yourself (or the rest of us) for not heading out into the night right that very minute to find that girl and give her a coat and a hat and some shoes and a home before the last match burns out.

That failure to act—right then, right now—it is unforgivable.

When you open your heart to love, when you allow beauty into your life, you open yourself up to pain. If you stop here, there is no God.

Stendhal’s syndrome wasn’t named until 1979, when Italian psychologist Graziella Magherini put a name to an experience she had heard described by over one hundred visitors to the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. Since over a million people visit the museum each year, it seems unlikely that Stendhal’s syndrome is common even among the most ardent art aficionados. Still, the Telegraph reports that staff at the Santa Maria Nuova hospital are accustomed to dealing with dizziness from people admiring the David. It happens.

What does this syndrome lead to? Maybe to nothing more than needing a glass of water under the Mediterranean sun.

I recently heard about a group of nuns in Uganda who run an orphanage, school, and birthing center for women. They work seven days a week. One nun is awakened several times each night to deliver babies. For some it’s already too late; the babies will not survive. But every time she’s called, she gets up, scrubs in, and reaches toward life.

If you keep walking toward it and into that pain, the world gives you back this utterly senseless beauty, and in some dizzying way you can’t understand (you ask for water, perhaps) you know God is there, flaming in that ferocious beauty.

Sitting on that hard pew I blinked against the sting in my eyes. Light draped softly across the statue of Jesus. The unforgivable was forgiven. The last notes drifted away, mote-like.

I don’t know anything of lightning-strike conversions or swooning on the banks of the Arno. This gift of art, painted, carved, sung, is to my soul like water over stone, the way it shapes things gently, over years. It is preparation to love, to be shattered, to love again. It is preparation to see to this other side of sadness, this lux asterna.

Shannon Huffman Polson is the author of North of Hope: A Daughter’s Arctic Journey. Her essays and articles have appeared in a number of literary and commercial magazines including High Country News, Cirque Journal and Alaska and Seattle Magazines. She can be found writing or with her her family in Washington State or Alaska, and always at her website, Facebook, and Twitter.