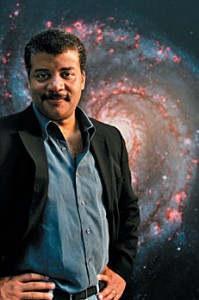

The nerd world felt a slight disturbance in the force a few weeks back, when the hottest new science popularizer, Neil deGrasse Tyson, argued that philosophy yields little value compared to science. The widely quoted statement that drew ire from philosophical types was Tyson’s observation, in response to someone’s admission to having been a philosophy major: “That can really mess you up.”

The nerd world felt a slight disturbance in the force a few weeks back, when the hottest new science popularizer, Neil deGrasse Tyson, argued that philosophy yields little value compared to science. The widely quoted statement that drew ire from philosophical types was Tyson’s observation, in response to someone’s admission to having been a philosophy major: “That can really mess you up.”

Anyone who has ever endured a philosophy class recognizes the truth in this claim, but it became a convenient placeholder for Tyson’s more objectionable comments, which amounted to an assertion that philosophy is navel-gazing sophistry which does not contribute to “our understanding of the natural world.”

“Practical men,” wrote John Maynard Keynes, “who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually slaves of some defunct economist.” This is doubly true of practical scientists, like the amiable Dr. Tyson, who are enslaved not to economists but to philosophers, even as they pronounce themselves independent of philosophical drudgery.

The amateur philosopher imprisoning Tyson and many of his colleagues is a centuries-dead Frenchman named Laplace, astronomer and mathematician by trade, who in his Philosophical Essay on Probabilities (he was not privy to Tyson’s cautions against philosophizing) expounded a notion that grips most science popularizers today, and a good many social planners as well. It is the notion that if we could capture all the data in the universe, we could understand the past and the present, and predict the future with certainty.

Knowledge equals data, in other words, and so what need have we when our analytical capacities progress by leaps and bounds, for the love of wisdom that is philosophy?

Leave aside the reality that delineating facts demand subjective judgment (the proper bounds of a statistical confidence interval, for example, were not handed down to Moses on tablets), alongside a few dozen other slippery matters that gave rise centuries ago to a branch of philosophy known as epistemology. Tyson may have no use for philosophy, but Albert Einstein observed that “science without epistemology is—insofar as it is thinkable at all—primitive and muddled.”

Leave aside as well the fatal flaw in Laplacean determinism, which is the annoying truth that even if we could know every scrap of atomic data about every human being alive today, we would still be unable to predict who will fall in love or hate or despair tomorrow, and to what truths and falsehoods these states of the heart will lead.

Statistical confidence intervals and the heart of man aside, Tyson has a point, which is that science gets things done. When’s the last time a philosopher cured a disease, or improved the quality of air conditioning, or developed a way to quintuple the number of television channels we can squeeze through a cable?

Scientists plumb the universe’s depths, guided by the exalted Scientific Method, which long ago displaced the Ten Commandments on the narrowing list of things every schoolchild is expected to know, and which looks something like this:

1) Ask a question

2) Gather observations

3) Define a hypothesis

4) Experiment

5) Analyze the results

Armed with this piercing light, man emerged from the darkness of medieval superstition to forge modern civilization, etc. There’s a lot of sophistication undergirding those five steps—things like parsimony, reproducibility, and so on—but they are the root of the scientific enterprise, and the reason Neil deGrasse Tyson believes we don’t need philosophy.

The only problem with this belief—even after we forgive Tyson’s ignorance of epistemology—is that the Scientific Method is a thoroughgoing lie.

I understand this is heresy, but in the spirit of inquiry, hear me out.

When you delve into the history of science, you don’t find a phalanx of impassive researchers asking questions, gathering data, and methodically testing hypotheses. You find visionaries—the scientists who make history, anyway—gripped by insights that precede their scientific tests. “Eureka,” Archimedes is said to have shouted, as he leaped from the bathtub where he first intuited a means of precisely measuring the volume of irregular objects. Eureka: I have found. His belief about reality preceded the proof.

Likewise did a PhD student named Louis de Broglie argue—with insufficient empirical data—that electron particles have physical waves. Albert Einstein, when Broglie’s skeptical thesis advisors wrote asking his opinion about the student’s theory, urged them to pass him, based on the elegance of his work. His theory felt right. A few years later the data emerged, and a couple of years after that, Broglie received the Nobel Prize in Physics.

“Only a tiny fraction of all knowable facts are of interest to scientists,” wrote scientist and philosopher Michael Polanyi. A scientist’s decision about what to explore—what drives him to the doorstep of the Scientific Method we were taught as children—is something altogether ignored by that method, but critical nonetheless to discovery: what Polanyi called “a sense of intellectual beauty.” Scientific discovery is, Polanyi believed, an emotional response to glimpses of an undiscovered reality. A scientist is very much like an artist in that regard.

Why does this matter? Because an ability to recognize intellectual beauty is cultivated. It is rooted in concepts like order, meaningfulness, transcendence. Our sense of beauty, in other words, shapes our capacity to make scientific discoveries. What happens to science when the shared sense of beauty and truth collapse? Polanyi would point to Nazi Germany and Communist Russia.

What’s more, just as philosophy governs science, science influences philosophy. If there is no transcendent beauty, if there is nothing but atoms and genes and a striving amongst them, then what’s wrong with euthanasia, and widespread sex changes, and pharmaceutical happiness? Tyson likely embraces them all. He probably can’t even imagine why someone wouldn’t.

And that is, fundamentally, the deeper problem with the pervasive ignorance and arrogance of modern scientists. Not that they seek to keep philosophy out of science, but that their denuded science impoverishes what we understand as wisdom.

This post was made possible through the support of a grant from The BioLogos Foundation’s Evolution and Christian Faith program. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of BioLogos.

Tony Woodlief lives outside Wichita, Kansas, and is the author of a spiritual memoir, Somewhere More Holy. His essays on faith and parenting have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, The London Times, and WORLD Magazine. His short stories, two of which have been nominated for Pushcart prizes, have been published in Image and Ruminate. His website is www.tonywoodlief.com.