It’s a chicken-and-egg kind of question I get all the time, but I don’t think I am the only one who has faced it: Am I more religious because I am a Southerner (as most of my Yankee friends seem to think), or do I seem more Southern because I am religious—never mind the fact that I am a longtime, generally happy exile to the Northeast Corridor?

It’s a chicken-and-egg kind of question I get all the time, but I don’t think I am the only one who has faced it: Am I more religious because I am a Southerner (as most of my Yankee friends seem to think), or do I seem more Southern because I am religious—never mind the fact that I am a longtime, generally happy exile to the Northeast Corridor?

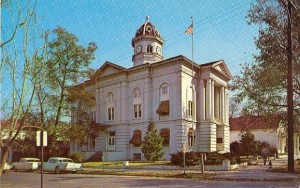

I’m sending this question out not only to some of the other Southerners who have proceeded through “Good Letters”—A.G. Harmon, Kelly Foster, Tony Woodlief (A.G., Kelly and I are from Mississippi, and Kelly and I are even from the same town)—but to all of you out there who might have some input on the matter.

For what so many of us Southerners—even those of us who are not, ahem, writers—seem to share is a great and abiding sense of mystery about the world. Perhaps this is due to the fact that, in the main, even now, most of us grew up around codes of manners and behavior that were commonly known, but rarely spoken of, and there was even less discussion about the realities of class and race that were all around us. And we could go off on long tangents about the various implications.

Whatever the reason, it is a characteristic of my life that the world has constantly seemed (and continues to seem) to be filled with portents about nearly everything, turns of circumstance that seem significant, as though a narrative arc cuts through my life as sharply as a ray of sun.

Two little anecdotes that a number of my fellow Yazooans—at least the Gen-X ones—may remember:

The Black Guy with His Head Under His Coat: Exactly like what he sounds like, the Black Guy with His Head Under His Coat was a young African-American man who walked up and down the residential streets of my hometown wearing an old suit coat, the lapels of which he held over his bent head, out from which cover he peered ominously as he walked.

How come y’all think he is the way he is? kids would ask each other. And I do not once, ever, recall this being expressed in a spirit of scorn. Rather, it was a worrisome sign—one that would seem to require some kind of repentance, or acclamation:

And I have seen the eternal Footman hold my coat and snicker,

And in short, I was afraid.

The Highway 49 Hooker: There is no evidence that the Highway 49 Hooker actually was one. She was a white woman in shorts, sunglasses, and giant black headphones who could be seen riding a bicycle at any time, day to night, on the highway from my hometown of Yazoo City to Jackson. What’s significant about this, for those of you who are used to thinking that the boundaries of communities are contiguous, a la Greenwich-CosCob-Norwalk-Westport-Stamford, the landscape between Yazoo City and Jackson is practically empty, flat fields interspersed here and there with stands of the forests that had once covered the land, only rarely dotted with a store, or a clump of houses. You’d be driving 65 mph on a blindingly hot summer day, 100 degrees and sultry (or more precisely, your mother would be driving), and all of a sudden, there’s she’d be, the Highway 49 Hooker, miles from anywhere.

Unlike the guy with his head under his coat, the Highway 49 Hooker did spark some salacious humor—how, for example, did she even get to be called hooker?

And I could keep going on and on: the gas-blue neon letters of the Yazoo Motel emerging out of the darkness when we drove back into town at night; my cousins’ crazy yard man Ollie who arrived from a stay in the state mental hospital and started looking around for dynamite to “blow up armadillos.”

I thought everyone thought that the world was a mixture of the strange and uncanny until I went up North to boarding school and in a meeting of the Human Relations Committee—a glorified values-clarification rap-session type-thing of the kind that Phyllis Schlafly and Mary Pride types would flip out about as indicating the dawn of the New Age—a sweet handsome boy named Ned Rosen from a wealthy Boston suburb said, “I just don’t understand all these crazy stories you talk about all the time. This stuff doesn’t even sound real.” (I think this was in reference to my mother.)

Ned Rosen ended up going to Harvard and later into the movie industry in California, and, plagued by his own ghosts, committed suicide in his early thirties. He thus unwittingly became part of the enduring mythos that trails through my own life, the very thing that was incredulous to him: I will light a candle at times in his memory (though we were never close friends), and find myself mourning all over again that someone who seemed so together would fall apart.

Believe it or not, this impulse to mystery is not, I think, chiefly a product of Christianity: I remember going to New England and thinking how unhaunted and literal both the evangelicals and Catholics—outside from the Italians and Poles—up there were (fake leather car coats and paperback NIV Bibles for the evangelicals; fish-sticks and genuflection for the Catholics).

So it must be a Southern thing, although I’ve long recognized similar impulses in Latin American and South Asian cultures: When I read One Hundred Years of Solitude, so much of the storytelling sounded so familiar, even as it wasn’t, and I wasn’t surprised, for I had heard Marquez had read Faulkner.

But really, theory fails me here: This was all just a ruse so I could tell you stories about the mysteries I—we—have encountered.

For they are relics, evidence, of the substrata of the Logos that enlivens all things.

A native of Yazoo City, Mississippi, Caroline Langstonis a convert to the Eastern Orthodox Church. She is a widely published writer and essayist, a winner of the Pushcart Prize, and a commentator for NPR’s “All Things Considered.”