First of All,

No. That’s sort of a nonsense question. The order we read things in can make a difference to how clearly we understand them, or the impression they leave on us; but, e.g., the statements “the sky is blue” and “rainfall comes from the sky” don’t change in truth-value based on which one you put first.

But also: kind of? After all, the order we read things in can make a difference to how clearly we understand them and the impression they leave on us.

This miniseries is about a way of structuring, or re-structuring, the Bible, which I’ve been thinking about more and more lately. However, we need some backstory for it to make sense. Get in the time machine, hit “back” for roughly twenty-three hundred years, and set the coordinates for 31° N, 29° E—we’re going to …

The Library of Alexandria

Catacombs beneath the Serapeion, an offshoot of

the Alexandrian Mouseion. Photo by the Institute

for the Study of the Ancient World, made available

under a CC BY 2.0 license (source).

There are lots of myths about the Library of Alexandria and its decline (for instance, said decline was probably gradual, not a singular torching1). The Library started out as a Μουσεῖον [Mouseion], which was a specific kind of institution in the classical world. Originally, these were temples to the Nine Muses (and often to Apollo as the lord of the Muses); sometime around the fourth century BC, they began also to be something more closely approaching a university, rather along the lines of the Athenian grove where Plato trained his pupils, a place called Ἀκαδημία [Akadēmia].

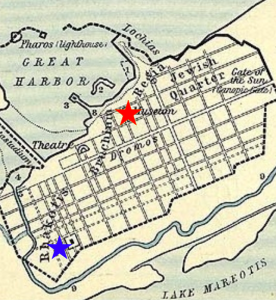

After Alexander the Great succinctly conquered the Persian Empire and even more succinctly died, his general (and relative) Ptolemy maneuvered his way into controlling Egypt. There he founded a dynasty of pharaohs—an unusually successful one, in fact, which held power for a solid three centuries. Now, Ptolemy was a scholar as well as a soldier; he, Alexander, and a handful of other sons of Macedonian nobles had basically gone to boarding school together under Aristotle in their early teens. Ptolemy and his dynasty wanted to make Alexandria an intellectual center, rivaling the likes of Athens, Heliopolis, Miletus, and Babylon. He2 therefore built a royally-sponsored Μουσεῖον there, and a library naturally formed part of its complex. To stock the Library, the Ptolemies sought not only Egyptian books, but copies of classic literature from all over—Attica, Ionia, Mesopotamia, and so on. Eminent scholars staffed the place; one of its early heads was Eratosthenes, a mathematician celebrated for his work on cartography even today.3 (When the Cæsars conquered Egypt, they became patrons of the Library of Alexandria in turn. By then it may have moved to an offshoot institution, slightly further in from the coastline, known as the Σεραπεῖον [Serapeion]; this was a temple to a syncretic Græco-Egyptian divinity, Serapis,4 which was also Ptolemy I’s creation. In Latin, these temple-college complexes were referred to as the Serapeum and the Musæum.)

A map of ancient Alexandria; red and blue stars

mark the Musæum and Serapeum respectively.

Based on a map by William R. Shepherd, used

in his Historical Atlas of 1923 (source).

One of the nearest realms (and a vassal of Ptolemaic Egypt at the time) was called Yehud. For the most part, the literature of its people, the Yehudin, existed only in their ancient language, Hebrew, which most of them hadn’t spoken in two or three centuries. It was a close relative of the Aramaic languages,5 and the Persians had made the Achæmenid variety of Aramaic an administrative language, so most Yehudin spoke Achæmenid as a mother-tongue; there were Yehudin that spoke Greek, but the only notable translations of the Hebrew literature were the targumim, paraphrases in Achæmenid Aramaic.

According to the story told in the extremely dubious Letter of Aristeas, in 285 BC, Ptolemy II sent word to Yehud asking for seventy-two translators (six from each of the Twelve Tribes) who could furnish the Library with a Greek rendering of the Hebrew Bible; in response, the high priest agreed and made his selections, whom he sent to Alexandria as requested, where they completed the translation in seventy-two days (naturally).6 This, of course, is the origin of:

The Septuagint

The name of this Greek version, ironically, is from Latin; septuāgintā means “seventy,” a rounding-errored nod to the number of its translators; its commonest abbreviation is the Roman numeral LXX, which does the same thing. For close to four hundred years, the Septuagint was the authoritative, and only, Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, and of some extra material as well.7 Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch (the one on the Levantine coast, not the inland one in Anatolia) housed particularly large communities of “Hellenists”—expatriate Jews whose native tongue was Greek, and who might know little to no Aramaic, let alone Hebrew—but they were dotted all over the Mediterranean, from Syria to Spain. (If we extend our search to Jews living outside Palestine in general, the map gets even bigger; there were already Jewish communities settled as far afield as Ethiopia and southern India.)

Once the Church came into being, the Septuagint was used by ancient Christian Hellenophones too. East of a line drawn roughly through the modern cities of Tabūk and Yerevan, Syriac Aramaic was the prime international language (the authoritative Syriac Bible is the P’shitta), though there were Greek settlements and even realms deep into Central and South Asia for centuries after Alexander. However, so far as I know, Syriac Christianity doesn’t significantly affect our story today. What does is the fact that, despite its popularity, the Septuagint is not and was not uncontroversial.

… And Its Discontents

The Torah Scribe (1876), by Maurycy Gottlieb.

The Septuagint contrasts with the Masoretic Text, the authoritative Hebrew version. This is named after its compilers, the Masoretes—Jewish scribes who lived from roughly the 400s, when the Sanhedrin was disbanded by the Byzantine Cæsars, to about the 900s, a couple of centuries into the Islamic Golden Age. (The name comes to us from a Hebrew word, מָסוֹרָה [mâsowrâh], which most probably means “tradition, [that which is] passed down.”)

The Septuagint is often denigrated as a bad rendering of the Hebrew. A famous example occurs in Isaiah 7:14: The Hebrew text contains the word עַלְמָה [ṛalmâh],8 whose meaning is “young woman” with a definite shade of “nubile” or “marriageable” in its connotations; both an unmarried girl and a young wife could be referred to by עַלְמָה. The translators of the Septuagint, perhaps picking up on the “marriageable” aspect, chose the Greek word παρθένος [parthenos] as its translation, but παρθένος usually refers to virginity. (In other parts of the Septuagint, the most frequent translation of עַלְמָה is νεᾶνις [neanis], which simply means “young woman.”) The preface to Sirach, which is not normally assigned chapter or verse designations, says outright that “we may seem to have rendered some phrases imperfectly. For what was originally expressed in Hebrew does not have exactly the same sense when translated into another language. Not only this work, but even the Law itself, the prophecies, and the rest of the books differ not a little.”

From a certain point of view, I’m going to be critiquing the Septuagint myself. However, I want to balance that a bit, because I think the Septuagint’s poor quality has been overblown. Manuscripts found among the Dead Sea Scrolls have shown that the textual history of the Hebrew Bible is not nearly so simple as “Masoretic Text good, Septuagint bad.” Some discrepancies between the two are due to flawed translation; however, others are good Greek renderings of a Hebrew text, but one that differed from what was selected by the Masoretes (whose finalization of the authoritative text came later).

The first page of Exodus from the

Complutensian Polyglot Bible, published in

1521 (with Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and

Aramaic text in different blocks).

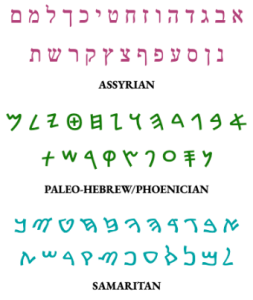

That might sound fishy, as if the Masoretes were pulling a fast one. For that matter, a certain sort of person may be inclined to just flip the script, viewing the Masoretic Text as flawed and the Septuagint alone as reliable. I don’t believe that’s what the Masoretes were doing, and when it comes to manuscript criticism, I don’t think “which is the good one and which is the bad one” is an illuminating question to ask. (Though if we absolutely insist on asking it, it’s worth pointing out that even the Greek Orthodox Church—which has, let us say, an attachment to the Septuagint—maintains not that it is the pure, original document and that the Masoretes muddied things, but that its changes from the Hebrew took place under divine inspiration. You don’t invoke that, or any, explanation for a change unless you admit that the change is there and needs explaining.) The last couple of centuries during which the Second Temple stood—from the Maccabee Revolt of 167-160 BC to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE—were a period of intense Jewish theological and literary foment, both in Palestine and abroad; cities like Antioch, Arbela (modern Erbil), Babylon, Ecbatana, and Rome were thriving centers of Jewish culture at this time. Multiple versions of the Torah were in circulation in Hebrew, including proto-Masoretic, proto-Septuagint, and early Samaritan recensions—every single copy, remember, created by hand; and we’ve alluded to the targumim, the Aramaic paraphrases that were commonplace in this era. It’s to be expected that variant readings would creep in, without anybody being intentionally dishonest.

…, And Also Its Contents

Two things are worth bearing in mind when looking over what books were included in the Septuagint. One—sorry, Aristeas—is that the Ptolemies didn’t commission this work for religious purposes; they wanted to round out the Library of Alexandria with “the Jewish classics,” whatever those might be.

The other is that when the Septuagint was created, the Judaic canon itself was not absolutely settled. The Sadducees had not yet come into existence, and the Essenes probably hadn’t either, so the debate was presumably less fierce and would have involved fewer books; but the Samaritans were already around, and, today at any rate, they only recognize (the Samaritan recension of) the Torah. Some books that now survive only or chiefly in Greek were composed originally in Aramaic or Hebrew; I Maccabees and Sirach are notable examples. Moreover, some works that may have been considered for canonization have survived only in occasional quotations, or left behind nothing but a title; no one today can read the Book of Jashar, the Book of the Wars of the Lord, or the Book of Iddo the Seer.

Jewish scripts. The Assyrian script (purple)

derives from the Phoenician (green), used in

pre-Exilic Canaan; post-Exile, only the Sama-

ritans used it, in their own variant (blue).

Below is a list of the books that formed part of the Septuagint. Each is listed under its common English name, followed by its name in the Septuagint, with transliterations and translations (save where the common English name simply is the best translation of the Greek).

______________________

The SEPTUAGINT

GOLD: CANONICAL IN JUDAISM AND ALL CHRISTIAN CHURCHES

BLUE: CANONICAL IN CATHOLIC, ORTHODOX, AND MIAPHYSITE CHURCHES

PURPLE: CANONICAL IN ORTHODOX AND MIAPHYSITE CHURCHES

RED: APPEARS IN ORTHODOX BIBLES IN AN APPENDIX

GREEN: NOWHERE CANONICAL; MAY RARELY APPEAR IN SOME BIBLES IN AN APPENDIX

Νόμος [Nomos], the Law

I. Genesis | Γένεσις [Genesis], “the Beginning”

II. Exodus | Ἔξοδος [Exodos], “the Departure”

III. Leviticus | Λευϊτικόν [Leuitikon], “Matter for Levites”

IV. Numbers | Ἀριθμοί [Arithmoi]

V. Deuteronomy | Δευτερονόμιον [Deuteronomion], “the Second Law”

Ἱστορία [Historia], History

VI. Joshua | Ἰησοῦς [Iēsous], “Jesus”

VII. Judges | Κριταί [Kritai]

VIII. Ruth | Ῥούθ [Rhouth]

IX. I Samuel | Βασιλειῶν Α [Basileiōn I], “I Kingships”

X. II Samuel | Βασιλειῶν Β [Basileiōn II], “II Kingships”

XI. I Kings | Βασιλειῶν Γ [Basileiōn III], “III Kingships”

XII. II Kings | Βασιλειῶν Δ [Basileiōn IV], “IV Kingships”

XIII. I Chronicles | Παραλειπομένων Α [Paraleipomenōn I], “I Remainders”

XIV. II Chronicles | Παραλειπομένων Β [Paraleipomenōn II], “II Remainders”

XV. I Esdras | Ἔσδρας Α [Esdras I]

XVI. Ezra-Nehemiah | Ἔσδρας Β [Esdras II]

XVII. Esther | Ἐσθήρ [Esthēr] (with about five extra chapters in Greek)

XVIII. Judith | Ἰουδίθ [Ioudith]

XIX. Tobit | Τωβίτ [Tōbit]

XX. I Maccabees | Μακκαβαίων Α [Makkabaiōn I]

XXI. II Maccabees | Μακκαβαίων Β [Makkabaiōn II]

XXII. III Maccabees | Μακκαβαίων Γ [Makkabaiōn III]

Σοφία [Sofia], Wisdom

XXIII. Psalms | Ψαλμοί [Psalmoi]

XXIV. Psalm 151 | Ψαλμός ΡΝΑ [Psalmos CLI]

XXV. Prayer of Manasseh | Προσευχὴ Μανασσῆ [Proseuchē Manassē]

XXVI. Odes | Ὠδαί [Ōdai]

XXVII. Proverbs | Παροιμίαι [Paroimiai]

XXVIII. Ecclesiastes | Ἐκκλησιαστής [Ekklēsiastēs], “the Preacher”

XXIX. Song of Songs | Ἆσμα Ἀσμάτων [Asma Asmatōn]

XXX. Job | Ἰώβ [Iōb]

XXXI. Wisdom of Solomon | Σοφία Σαλομῶντος [Sofia Salomōntos]

XXXII. Sirach | Σειράχ [Seirach]

Προφήται [Profētai], the Prophets

XXXIII. Hosea | Ὡσηέ [Hōsēe]

XXXIV. Amos | Ἀμώς [Amōs]

XXXV. Micah | Μιχαίας [Michaias]

XXXVI. Joel | Ἰωήλ [Iōēl]

XXXVII. Obadiah | Ὀβδιού [Obdiou]

XXXVIII. Jonah | Ἰωνᾶς [Iōnas]

XXXIX. Nahum | Ναούμ [Naoum]

XL. Habakkuk | Ἀμβακούμ [Ambakoum]

XLI. Zephaniah | Σοφονίας [Sofonias]

XLII. Haggai | Ἀγγαῖος [Aggaios]

XLIII. Zechariah | Ζαχαρίας [Zacharias]

XLIV. Malachi | Μαλαχίας [Malachias]

XLV. Isaiah | Ἠσαΐας [Ēsaias]

XLVI. Jeremiah | Ἱερεμίας [Ieremias]

XLVII. Baruch | Βαρούχ [Barouch]

XLVIII. Lamentations | Θρῆνοι [Thrēnoi]

XLIX. Letter of Jeremiah—Ἐπιστολὴ Ἰερεμίου [Epistolē Ieremiou]

L. Ezekiel | Ἰεζεκιήλ [Iezekiēl]

LI. Daniel | Δανιήλ [Daniēl] (with about three extra chapters in Greek)

(Appendix)

LII. IV Maccabees | Μακκαβαίων Δ [Makkabaiōn IV]

LIII. Psalms of Solomon | Ψαλμοὶ Σαλομῶντος [Psalmoi Salomōntos]

______________________

The order of the books differs in places, but the layout of the Septuagint is where we get the layout of the Christian Old Testament: law, history, poetry, prophecy. One interruption of this structure is common in Catholic Bibles: I and II Maccabees often stand at the end of the Old Testament (rather than between Esther and Job, as the Septuagint’s logic elsewhere would predict).

The Role of the Greek Bible

So these fifty-three books were the Hebrew Bible in Ancient Greek. Right? Mmm—yes and no.

Yes: because the Septuagint was the only important translation of the whole Hebrew Bible into Ancient Greek from the early third century BC until the early second AD.9 There were Jews, mainly outside the Holy Land, who knew Scripture primarily or even solely through it. More strikingly, the Apostles weren’t above quoting readings specific to the Septuagint to make theological points. For instance, in Ephesians 4:7-13, St. Paul’s argument depends grammatically upon the Septuagint’s wording of that Psalm; it won’t work with the Masoretic recension of the text, which reverses the direction in which the verb is operating and has a different direct object.

Part of the Nile mosaic of Palestrina

(1st c. BC); Palestrina is a town east of Rome.

But, also No: for two reasons. First, even if we assume (which is exceedingly unlikely) that the Judaic canon was ever the same as the Catholic Old Testament canon, all the purple, red, and green in that list indicate the degree to which the Septuagint was not just “the Hebrew Bible in Greek.” A few of those titles, like I Maccabees or Sirach, were apparently first composed in Hebrew, but several were written in Aramaic or even Greek right from the beginning, and one of the principles ultimately endorsed by Judaism for deciding the canon was that the original language of composition must be Hebrew. An admixture with Aramaic was tolerated, as in Daniel and Ezra; original composition in Greek, on the other hand, as in books like II Maccabees or Wisdom of Solomon, is disqualifying.

The Architecture of the Tanakh

The other major reason is the arrangement of the Hebrew Bible. I don’t just mean surface discrepancies—stuff like the books of Samuel and Kings both getting split in half and also renamed as part of the tetralogy “Kingships.” I’m talking about a structure that makes a theological point, all on its own.

One of the Hebrew names for the Bible is the Tanakh. This is an acrostic. The letters T-N-K (with a‘s inserted as a kind of default vowel) stand for the three basic devisions of the Hebrew Bible: the Torah, meaning “instruction” or “law”; the Nevi’im, “prophets” or “oracles”; and the Kethuvim, which simply means “writings” or “books.” This sounds like it aligns with what Jesus says here and there about “the law and the prophets and the psalms,” especially since Psalms is the first book of the Kethuvim. That said, which books fit where isn’t necessarily where you might expect.

Painting of Ezra the Scribe (3rd c. CE),

anonymous, synagogue at Dura-Europos

(in the far east of modern Syria).

The contents of the Tanakh are below. The common English names of the books are listed first, followed by their Hebrew originals, with transliterations (and translations, where the latter differ from the common English—or in several cases, new adaptations of the original names to English phonology that hew closer to the Hebrew).

______________________

The TANAKH

GOLD: תורה, THE LAW

INDIGO: נביאים ראשונים, THE FORMER PROPHETS

VIOLET: נביאים אחרונים, THE LATTER PROPHETS

RED: כתובים, THE WRITINGS

תּוֹרָה [Towrâh], the Law

I. Genesis | בְּרֵאשִׁית [B’rêshyth], “In the Beginning”

II. Exodus | שְׁמוֹת [Sh’moth], “Names”

III. Leviticus | וַיִּקְרָא [Wayiqra’], “And He Called”

IV. Numbers | בְּמִדְבַּר [B’midhbar], “In the Desert”

V. Deuteronomy | דְּבָרִים [D’varym], “Sayings”

נְבִיאִים [N’vy’ym], the Prophets

VI. Joshua | יְהוֹשֻׁעַ [Y’howshûaṛ], “Yehoshua”

VII. Judges | שׁוֹפְטִים [Showfṭym]

VIII. Samuel | שְׁמוּאֵל [Shmuu’êl] (I & II), “Shmuel”

IX. Kings | מְלָכִים [M’lâkhym] (I & II)

X. Isaiah | יְשַׁעְיָהוּ [Y’shaṛyâhuu], “Yeshayahu”

XI. Jeremiah | יִרְמְיָה [Yirmyâh], “Yirmyah”

XII. Ezekiel | יְחֶזְקֵאל [Y’chezqê’l] “Yechezqel”

XIII. The Twelve Prophets (counted as one book)

…..1. Hosea | הוֹשֵׁעַ [Howshêaṛ], “Hoshea”

…..2. Joel | יוֹאֵל [Yow’êl], “Yoel”

…..3. Amos | עָמוֹס [Ṛâmows]

…..4. Obadiah | עֹבַדְיָה [Ṛovadhyâh], “Ovadyah”

…..5. Jonah | יוֹנָה [Yownâh], “Yonah”

…..6. Micah | מִיכָה [Mykhâh]

…..7. Nahum | נַחוּם [Nachuum], “Nachum”

…..8. Habakkuk | חֲבַקּוּק [Chàvaqquuq], “Chavakkuk”

…..9. Zephaniah | צְפַנְיָה [Tz’fanyâh], “Tzefanyah”

…..10. Haggai | חַגַּי [Chagay], “Chagai”

…..11. Zechariah | זְכַרְיָה [Z’kharyâh]

…..12. Malachi | מַלְאָכִי [Mal’âkhy]

כְּתוּבִים [K’thuvym], the Writings

XIV. Psalms | תְּהִלִּים [T’hillym], “Praises”

XV. Proverbs | מִשְלֵי [Mishlêy], “Parables”

XVI. Job | אִיּוֹב [‘Iyowv], “Iyov”

XVII. Song of Songs | שִׁיר הַשִּׁירִים [Shyr ha-Shyrym]

XVIII. Ruth | רוּת [Ruuth]

XIX. Lamentations | אֵיכָה [‘Êykhâh], “How”*

XX. Ecclesiastes | קֹהֶלֶת [Qoheleth], “the Sage”

XXI. Esther | אֶסְתֵּר [‘Estêr] (without Greek chapters)

XXII. Daniel | דָּנִיֵּאל [Dâniyê’l] (without Greek chapters)

XXIII. Ezra-Nehemiah | עֶזְרָא-נְחֶמְיָה [Ṛezrâ’-N’chemyâh] (originally one book), “Ezra-Nechemyah”

XXIV. Chronicles | דִּבְרֵי־הַיָּמִים [Divrêy ha-Yâmym] (I & II), “Words and Days”10

*I don’t know why the published display insists on producing a run-on line here, instead of going down to the next line like it’s instructed to, and does everywhere else. It doesn’t do that in the display it shows me while writing; I have tried every html tag known to man to force it to cooperate, and, nope. It drives me insane that something this simple should be this unfixable. Point is, if you were wondering what the significance of this change in formatting was, there isn’t one.

______________________

This is a much more elegant arrangement! One noticeable difference is that, unlike the Septuagint or the Protestant or Catholic Old Testaments, the Tanakh has twenty-four books—a lovely number, one rich with possible symbolic meanings, It’s the number of hours in a day, making it a good symbol for both time and eternity; it’s also twice the traditional numerical symbol of Israel (twelve), allowing it to represent God’s people in whatever twofold sense may be relevant: past and future, male and female, living and dead, in the Holy Land and in the Diaspora, etc.

Four books are kept intact here that usually appear split in Christian Bibles: Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, and Ezra-Nehemiah. (Additionally, the Minor Prophets are listed as a single twelve-part book, though note that the Minor Prophets of the Tanakh do not include the Book of Daniel.) It may seem odd that Ezra-Nehemiah was originally a single book, but believe me: This ain’t the half of it. If you care to try and straighten out for yourself the identities and designations of the dozen-ish books titled by some version of the name “Ezra” (or—you’ll be seeing a lot of this, it’s worth knowing—Esdras in Greek), then by all means, stop it this instant. I can’t just leave you to your fate; I don’t care what you’ve done.

DO NOT sign in to edit.11

(Image courtesy of the SCP Database Wiki; source.)

Look again at the end of the final section. Here we find three books—Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and Chronicles—that may seem totally unconnected to one another at first glance. However, there’s a subtler sense in which these three books are the key to the whole architecture of the Tanakh.

Footnotes

1If there was a single primary destruction event in the Library’s history, it most likely took place during the reign of Emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275), during the aptly-named Crisis of the Third Century. In 270, the Roman East was declared the Palmyrene Empire by one Queen Zenobia. In 272, Aurelian reconquered the Palmyrene Empire; as the largest city of that Empire, Alexandria was involved in the war, so the Library may have been attacked—but we don’t know. (Zenobia’s fate is also uncertain, and in my opinion a name like that is just begging to be memorialized in an opera.)

2Or possibly his son, Ptolemy II, but which Ptolemy it was is beside the point for our purposes.

3In particular, he worked out how to project a globe onto a flat surface—essential to the accuracy of any flat map showing more than a few square miles—and calculated the circumference of the earth to within an error margin smaller than 2%!

4Serapis (or Oserapis) was an amalgam of two Egyptian deities, the Apis bull and Osiris; the god was Græco-Egyptian in origin and style (e.g., he appeared only in anthropomorphic form, not in an animal-headed emblem). He was sometimes identified with deities such as Asclepius, Dionysus, Pan, Dis Pater, Jupiter, or Amun. This may make Serapis sound a little incoherent, but it also goes some way to explaining his popularity in the Hellenistic and early Imperial eras (roughly 300 BC to 300 CE): His worship had a lot of ways of appealing to people, and he fit easily into the nascent syncretic monotheism of the Roman Empire in the second to fifth centuries.

5“Aramaic” in the singular turns out to be a bit of a misnomer. The word is less analogous to, say, “French” than to a word like “Romance,” denoting a family with several distinguishable members.

6While no individual part of this narrative is strictly impossible, stylistically, it’s downright cheap—the kind of story that is to real religious practice what a romance novels is to marriage. Moreover, several of the historical details in the Letter of Aristeas don’t make any sense. It states that Ptolemy II sought this work at the suggestion of Demetrius of Phalerum, an early head of the Library—but if so, Demetrius must have shouted awfully loud for Ptolemy II to hear him, since the pharaoh had exiled him for backing a rival candidate for the throne. And even if the Ptolemies had had any reason to know or care about the Twelve Tribes (which they did not), several of them had effectively disappeared at this time. Benjamin, Judah, and Levi were still extant; descendants of refugees who fled to Judah after the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom may have kept some other lineages alive, especially larger or more important tribes—Ephraim, Manasseh, Naphthali—but there are hints that others, e.g. Reuben and Simeon, were in decline even before the monarchy was instituted. (There might be a garbled basis in fact here, all the same. If any such formal request were made by the Ptolemies, it would doubtless have been dealt with by the Sanhedrin, whose full number was seventy-one; seventy-two is not only a multiple of a few numerological favorites—three, four, six, twelve—but a significant number in the measurement of axial precession. Without getting into details, the earth’s north-south axis swivels in a circle, at the same time as we both spin and orbit the sun; about a degree of swivel can be detected with the naked eye, in a period of approximately seventy-two years. The point is, there may have been motives to turn seventy-one into seventy-two while describing the origin of the Septuagint, and other changes—like the seventy-odd people concerned being turned from the Sanhedrin [“I don’t know, it’s a boring thing foreigners have”] into the commissioned translators [“oh, I know what these are, Greeks have these“]—have more obvious causes.) Probably the only reliable fact in the Letter of Aristeas is that the Septuagint was most likely begun or finished in 285 BC!

7All Christian traditions leave out some standard contents of the Septuagint; Protestant Bibles leave out everything excluded by the Jews, but the Catholic canon, the Orthodox, and even the notoriously large Ethiopic canon, all exclude at least some of the Septuagint’s contents.

8You’ll usually see this word transcribed almah. I use a transliteration system which interprets ע (ayin) as having been, in Classical Hebrew, the “guttural” r-sound used in French and German. (This sound appears in Modern Hebrew as the pronunciation of ר [resh]—according to this theory, the classical resh was a tapped or trilled r.)

9In the second century CE, perhaps due in part to the controversies between the primitive Church and early rabbinic Judaism, three more Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible were created: those of Aquila of Sinope (not the Aquila from Acts), Theodotion, and Symmachus. The Septuagint remained traditional among Christians, but the new versions were not without honor; in the early third century, Origen used all four Greek versions to create four of the six columns in his Hexapla or “Sixfold Edition” of the Old Testament (the other two columns were the Hebrew text and a transcription of it into Greek letters). This was a forerunner of the modern critical edition, and it is truly saddening that it survives only in fragments.

10I could confirm or deny that this not-quite-accurate rendition of the Hebrew was prompted by the phrase’s resemblance to Hesiod‘s Works and Days, but I choose not to.

11“Please, for the love of Pete, do not feed the Hudge.”