The post, continued from yesterday, is adapted from a commencement address given at the Seattle Pacific University MFA in Creative Writing graduation ceremony in Santa Fe, NM on August 9, 2014.

5: Make your writing a prayer.

This point may sound overly pious but I don’t mean it in a pietistic way.

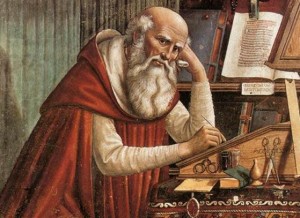

I’m not suggesting that you imitate Augustine, who wrote the entirety of the Confessions as a single, continuous prayer. But what he did in that book offers us some clues about how to be better writers.

Every prayer, even the short ones we blurt out in times of need, is language that is shaped to some extent: consecrated speech. In prayer we search for words to express our need, seek help, and give thanks. The very act of prayer is thus a search, a journey.

Augustine peppers his Confessions with questions, and I can’t think of a more spiritual form of devotion than questions that are posed with passion and genuine openness to the unknown, the unexpected sources of grace.

What if everything you wrote was a prayer to God and a prayer for communion with your reader?

6: Choose Incarnation over Ideology.

The Confessions is full of philosophy and theology, which can sometimes be a chore to get through, but those heady abstractions entailed plenty of flesh and blood consequences for its protagonist. In many respects Augustine’s time is vastly different from ours, and yet it’s surprising just how contemporary his story sounds in our ears. As the Roman Empire came to an end, the cacophony of religious sects and political parties made for all-out culture wars.

Both as a Manichean and as a Platonist, Augustine felt the particular pleasure of self-righteous enlightenment that is the hallmark of ideology. But because ideology is an artificial system imposed on reality rather than a picture built up from a long, loving gaze at reality, it becomes dangerously abstract. The ideologue’s humanity is riven in two: attempting to live like the angels floating above experience she finds herself suddenly reentering the world as a beast. The head becomes estranged from the heart.

Ideology offers a sense of separateness and righteousness, which is why Augustine found the messy, muddled Christian church, with its doctrine of Christ as fully human and fully divine, too distasteful to embrace for so long. This Church, whose first two leaders were a reformed betrayer and a reformed persecutor, seemed hell bent on mixing large doses of mercy in with justice, and appeared to believe that its adherents should live out their lives embracing the ambiguity of human conflicts and the need to embrace mystery rather than certainty.

Augustine’s conversion was ultimately a surrender to this muddle, a willingness to affirm the created order in all of its brokenness as the dwelling place of God’s spirit. Which is why the keynote of Christian faith is not moralism but the encounter with a presence that loves us, warts and all, all the way to our destiny.

When writers are doing their work properly, they restore our sense of living within the ambiguity and mystery of the world. The writer’s hope is that the more she pays attention to creation the more the hints and signs of grace will flash out, often without her knowing it. The best writing is sacramental, the body of the world broken and offered to us.

7: Follow your restless heart.

Both the Confessions and the Aeneid are epic tales about vocation and its high cost. Few professions are more given over to agonizing about vocation than that of the writer, who seems eternally willing to doubt herself, even long after a string of successful publications. If there were an Olympics for neurotics, writers would take home the gold in every event.

There are times when, as in the Aeneid, it seems that we will never get beyond all the obstacles that stand in the way of our vocation and that, even if we do move past those obstacles, the cost will be too high—to our humanity, and to those around us.

And there are times when, as in the Confessions, it seems that our anxiety and sense of loneliness as writers will never go away. Augustine said to God that “our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee,” and there are times when we long for rest, even if it means giving up what we thought we were called to do.

You may be tempted to think that your restlessness is the enemy, but believe me when I say that it is not. That restlessness is God’s gift to you, that insatiable desire, that hunger of love, which has been planted deep within you. Without that restlessness you would never seek true rest; instead, you’d accept stagnation.

Augustine came to see that when memory and desire meet, the imagination—the urge to give shape to our experience and move from fragmentation to unity—is at its peak of creativity.

Follow where your restless hearts lead you. As long as you heed Augustine’s advice—to allow your desire to embrace the world without attempting to possess it, to seek the infinite within the finite—your heart will speak to the hearts of others.

So let me end with some words of Augustine, words that might not make you the authors of future bestsellers, but words that are good, true, and beautiful—and certainly not loquacious.

But when I love you, what do I love? It is not physical beauty nor temporal glory nor the brightness of light dear to earthly eyes, nor the sweet melodies of all kinds of songs, nor the gentle odour of flowers and ointments and perfumes, nor manna or honey, nor limbs welcoming the embraces of the flesh; it is not these I love when I love my God. Yet there is a light I love, and a food, and a kind of embrace when I love my God—a light, voice, odour, food, embrace of my inner man, where my soul is floodlit by light which space cannot contain, where there is sound that time cannot seize, where there is a perfume which no breeze disperses, where there is a taste for food no amount of eating can lessen, and where there is a bond of union that no satiety can part. That is what I love when I love my God.

Gregory Wolfe is the founder of Image and the Director of the Center for Religious Humanism. He also serves as Writer in Residence and Director of the MFA in Creative Writing program at Seattle Pacific University.He has published essays, reviews, and articles in numerous journals, including Commonweal, First Things, National Review, Crisis, Modern Age, and New Oxford Review. He received his B.A., summa cum laude, from Hillsdale College and his M.A. in English literature from Oxford University. His website is www.gregorywolfe.com.