Continued from yesterday.

Continued from yesterday.

On the first day of my class “Spiritual Autobiographies: Theirs and Ours,” a few students shared that they weren’t “spiritual people.” Why, I wondered, did they sign up for this elective class?

Some of them, I would learn later in the semester, had been deeply wounded by religion. A few said that religion had been forced on them by their parents.

At this moment of emerging adulthood, it was time to turn away, to turn another way. Neither the students nor I realized, as class began in mid-August, that some of their wounds, whether exposed in speech, writing, or—to anyone paying attention—in silence, would become sites of inquiry and that inquiry itself might begin a process of healing.

One example.

For her first paper, one student wrote a passionate letter-essay to her parents.

Dear Mom and Dad (and whomever else I made a hypocrite in the eyes of God), the letter-essay begins.

I suppose all the baptismal water has evaporated out of my pores by now. Every inch of my body must scream sin to you. I wonder what happened. When did I make you feel that you failed as a disciple of Christ? I am sorry that I made it impossible to keep the promises you made twenty years ago while I was crying in your arms in a gown of white. I feel guilty knowing that even though you believe in the existence of heaven, you do not have the reassurance that you will meet me there one day. I am sorry I do not believe in what you do.

I am not you. That’s what she says to her parents.

Has there ever been a young woman or man who has not had to make such a declaration to his or her parents, if not in words then in attitude; if not in attitude then in action? How many, though, as they separate and harden into their individuated selves, are able to imagine and care about how their rejection of their parents’ beliefs affects their parents?

Her sensitivity to the feelings and convictions of her parents does not, however, lead her to suppress her bitterness at having been required, by them, to attend Sunday school weekly and having had a hymnal forced into her hand when she wasn’t praying—because she wasn’t interested in praying—with the congregation.

In the third paragraph of her inquiry (“I wonder what happened”), she recognizes that her parents weren’t the problem. “You were only keeping your promises,” she acknowledges. The problem was their God, who, as she sees it, fails repeatedly to keep his promises.

A boy from Bible camp—the first boy her best friend in middle school kissed—chokes to death on a roll at his church’s youth group. Later, the writer’s boyfriend, whose ancestors were murdered in the Holocaust, is sickened by the smell of a classmate’s burning flesh. That boy set himself on fire at school. How could a loving God allow such things to happen to young, innocent people?

She comes to feel, she writes, as if she is in “some type of abusive relationship where I was trying to justify his [God’s] actions through our love.”

Had her parents taught her how to pray, had they taught her that doubt is not only okay but it as a necessary part of a mature religious life, she might have had some way to reconcile experience with belief.

She concludes:

It’s been over five years since I’ve sincerely prayed to God, but I get down on my knees now to ask him to lift your burdens. Please God do not hold them to their promises they made twenty years ago, for they were naïve to the resistance I would put against them. They were unaware that I seek spirituality not from a pulpit or a white robe but from within.

With all my love,

In the end, she prays for her parents, prays to God in whom she no longer believes.

Wounded by religion. Yet, deep down (beneath the details of any particular religion), the values fundamental in most if not all religions remain in her (and others) unharmed: compassion, forgiveness.

Are compassion and forgiveness part of one’s spiritual life? What about the ability to see the world—its material and immaterial aspects—through the minds, hearts, and habits of others? What about the challenge of remaining in loving relationship to those who have loved and harmed you?

We didn’t talk at all—or at least not very much—about God in class.

Early in the semester, beginning with Girl Meets God, our first assigned text, I shared what I called “keywords” from each day’s assigned reading. Loyalty, infidelity; darkness, light; waiting; improvised prayer; desire, temptation, betrayal; finding your teacher; I believe: these are some of the keywords I noted from the first two sections of Girl Meets God.

Why did I choose these words and others like them? They all named experiences I assumed everyone in the room, religious or not, had had or could imagine themselves having. None of them pointed exclusively to God.

The first paper assignment: choose one term from the list of keywords and use it point you toward an essay. The keyword chosen by the writer of the letter-essay: “forgiveness.”

If I teach this class again, or the next time I use a text in any class that gives us an opportunity to talk about what writers talk about when they talk about God, I will remember my responsibility, as an educator, to inquire, with intellectual integrity, into everything that’s relevant, including those parts of our experiences that, because they are difficult to talk about, may be avoided, dismissed as untrue, or merely marginalized in the setting of a public university.

I will also remember my student’s letter-essay. I will try to summon the wholeheartedness—“There is nothing so whole as a broken heart,” says the Kotzker Rabbi—that she brought to her courageous work, and I’ll ask, “what about God, what about God?”

Richard Chess is the author of three books of poetry, Tekiah, Chair in the Desert, and Third Temple. Poems of his have appeared in Telling and Remembering: A Century of American Jewish Poetry, Bearing the Mystery: Twenty Years of IMAGE, and Best Spiritual Writing 2005. He is the Roy Carroll Professor of Honors Arts and Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. He is also the director of UNC Asheville’s Center for Jewish Studies.

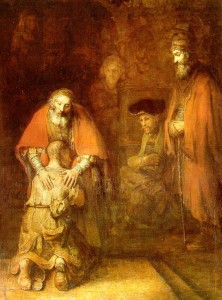

Image above painted by Rembrandt, used under a Creative Common License.