I am. This is not pure conceit.

I am. This is not pure conceit.

My tea (Irish Breakfast, decaf, as it’s nearly 9 p.m.) is still warm, thankfully—I’d left it in the kitchen to steep, knowing full well I’d forget it once I checked my phone, remember it once I’d scrolled through apps long enough to be disgusted with myself, and wonder how much I might have done with my life had Twitter never been invented.

I must pray. I attribute everything I have done to prayer. I don’t think God will fail me in the future if I pray, if I try to believe.

My roommate had her Bible in her lap when I came through the front door—she told me she was grumpy, and I stood there listening to her recount her “mopey” day (as she called it) and her lack of success in preparing for her Bible study tomorrow.

She picked up the Bible and shook it. “Speak to me!” she pretended to yell, and I laughed in a way that felt a bit like guilt, a bit like relief, as I remembered how I once prayed for more margins in my days, for the willpower to create those margins so I could listen and write and breathe.

Now I struggle to remember the last time I woke up early enough to read and recite the morning liturgy in its entirety, a time when my eyes didn’t flit to the clock as my lips mouthed the collects for the day.

Oh dear God, please don’t let me be taken in by this vast nonchalance with which the social scientific world looks at eternity!

How can I, dear God, when the concept of anything like “eternity” causes me to crawl back into comfortably concrete ideas that I can understand, slip them on like sweaters?

(I have scribbled a mental note for myself: Come back and read this journal. Often.)

I am so tired—saturated to satiety with this orb. I love to sleep. I wish I could sleep a year—wake up with so much behind me.

We were driving back home earlier that day, I was mid-sentence, when the notification lit up the screen—“At least 20 killed by gunman at Texas church…”—and that sick, thick thud of thoughts hit. Suddenly nothing is important (everything is meaningless, a chasing after wind). Suddenly everything is much too important and must be grabbed, snatched, held onto for dear life: every passing tree, every sunset, every quiet breath.

Now I would like to write, but would rather sleep—usual condition.

Would rather favorite a few tweets.

Would rather reheat my mug of tea.

Would rather open a new tab.

Would rather…

The things that go around in my head and won’t stop are becoming so trivial, so boring, so irritating that it irritates me to write them.

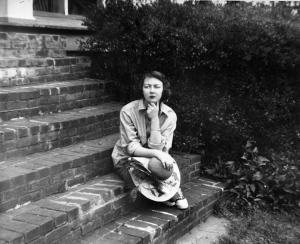

“To be an ‘author’ entails having ‘authority,’ as the etymological connection of the two words suggests, something, until recent history, denied to women by lack of education, legal rights, or public roles,” explains Karen Swallow Prior, writing about O’Connor’s journal in The Atlantic.

I tell myself I am educated. I do not tell myself I have authority. Thus the cursors on the open Word documents continue to blink while I pick up my phone instead of type; the pages of my notebooks fill with prayers for confidence.

“I hope no one ever reads my journal someday,” my roommate says. I’d read her a paragraph of O’Connor’s journal and we’d both commented something like “wow” and “mind blown” and then I’d started to read again, silently.

“But”—she continues—“I suppose if people were reading my journal someday, that means I must have written something else really good.”

It gives me a sense of immense comfort to think that Flannery O’Connor, the Flannery O’Connor, may have had similar hopes—may no one ever read this—flit through her mind as she wrote these entries. (But she wrote them still.)

It is pleasanter to daydream than to work.

Tomorrow is Monday. Tonight is my chance to close my laptop, pack my lunch bag, brush my teeth, steel myself for a new, freshly opened week. Tonight is my chance to stare at the blinking cursor on the page, to think about all the words I could have written had it not been for smart phones and Facebook and my own fear of saying something, anything, because how could it possibly be that important?

I wish I could flush my mind—and other people’s.

I wish I could, too.

But for now, I grab a pen. I start to highlight the lines that a young Mary Flannery O’Connor wrote in a neat cursive in the early 1940s: the lines that, in their wonderings and wanderings, offer me something that feels a lot like relief, a lot like hope.

For now, I am—this is not pure conceit.