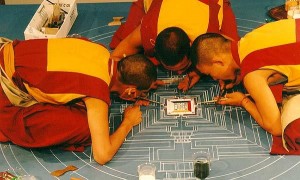

After the initial cleansing ceremony, they worked in silent concentration. Hour after hour they knelt in their maroon robes and yellow shawls, bent over their meticulous labor, creating designs and pictures with brightly colored sand.

After the initial cleansing ceremony, they worked in silent concentration. Hour after hour they knelt in their maroon robes and yellow shawls, bent over their meticulous labor, creating designs and pictures with brightly colored sand.

They were Tibetan Buddhist monks from Dehra Dun, India, making a stop in my hometown as they toured America. They had set up in the chapel at Randolph College and spent a week creating an elaborate Medicine Buddha mandala.

From the reading I’ve done about the mandala, I understand that it is believed to represent, and take part in, a great multi-layered reality that consists of countless circles—a nucleus in a cell in an organism in an ecosystem on the earth in the solar system in the Milky Way, etc.

The word mandala itself comes from Sanskrit and means circle or completion. The purpose of a Medicine Buddha mandala is to heal by restoring completion, or wholeness.

The mandala they made was beautiful. All the bright colors, intricate patterns, every small part, every tiny lotus leaf symbolic of something. But did it really do any healing?

The monks were peaceful, as a friend said, “comfortable in their skin.” One student called them chill. There is no doubt that everyone who was around them felt the positive energy of their presence.

I thought to myself that even if there were no spiritual healing, there’s no doubt that these monks spread a sense of peace, a feeling of good will—and hasn’t research proven that these things can be healing, can improve your health and quality of life?

But is there something deeper? An actual spiritual level at which healing takes place? What healing power are the monks calling on? Good feelings? We know how important attitude is when fighting illness, but is that what these monks believe is going on? And what did all these westerners coming by to watch—academics most of them at that—think of it?

I can’t say what others were thinking of the event. I thought it was interesting, cool, promoted cultural understanding, and good will. But real healing? I wasn’t buying it. I’m guessing, polite as everyone was to the monks, most of the others weren’t buying it either.

I’m sorry, but it sounds ridiculous.

I think it is nice that there are people in the world who believe this kind of thing, but I admit that I concluded, even though real good feelings come from the work they do, that in the end the monks have devoted their lives to a dream, a fairytale. They are whistling in the dark, pretending to have some control over what we simply cannot control.

When I was in Santa Fe for my MFA residency, I rode out with friends to see El Santuario de Chimayo, a sight where miraculous healings are said to have taken place. The chapel there is a pilgrimage destination for those seeking healing for themselves or their loved ones. The little chapel’s walls are shaggy with dangling shoes—lots of baby shoes—crutches, thousands of photographs. Prayers all. Acts of faith.

Inside there is a hole full of healing soil. You can scoop the dusty dirt up with your hands, take some. The priests will refill it with more from the sacred healing place.

A friend standing beside me, who was once Wiccan, said, “This all just looks like magic to me.” I have to admit I agreed.

We certainly have our share of faith healers around here—and I’m not talking about the phony ones on TV; I’m talking about the ones who believe their prayers and anointings are effectual.

I once sat and listened to an apologist share research, studies that attempted to show with empirical evidence that seriously ill people who are prayed for recover at higher rates than those who go without prayer.

But if it can be tested and quantified, doesn’t that make whatever they are praying to some kind of a force they tap into and not a personal being? The Great physician? Tibetan Buddhists call the Medicine Buddha The Supreme Physician.

The tradition in which I was raised would say that they are tapping into something spiritual all right. Evil disguised as an angel of light. They would also pay lip service to the healing power of prayer, at least inside the church doors on Sunday morning—once you stepped outside, you’d best get yourself to the doctor.

I think of the quote attributed to the great curmudgeon H.L. Menken: “The philosopher is a blind man in a dark room looking for a black cat that isn’t there. The theologian has found it.”

I remember laughing the first time I read it, but immediately wondering why Menken thinks he’s the one with clear vision, the one who has turned the light on in the room, and can see every corner of it to declare with such certainty that the cat is not there.

I’m afraid that’s been my attitude toward these monks. Not only is it patronizing, it assumes I have exhaustive knowledge of something about which I actually know precious little.

When all their painstaking work was complete, the monks destroyed the intricate mandala they had just created. They poured the sand into the James River, to send this healing power down the river, to the sea, and out across the world.

I find that this last stage of the mandala suits my melancholy temperament best. The monks’ dismantling of the mandala symbolizes the impermanence of all that exists—including healing. Healed once, people will again get sick.

Brought back from the dead, Lazarus will again have to die.