Another exercise. This one an exercise in seeing deeply, visualization, sketching from memory, and composing a written sketch of a photograph held in memory.

Another exercise. This one an exercise in seeing deeply, visualization, sketching from memory, and composing a written sketch of a photograph held in memory.

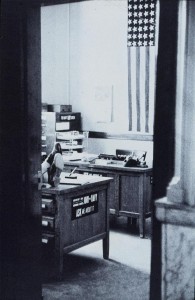

The photograph: Robert Frank’s “Navy Recruiting Station, Post Office, Butte, Montana,” published in his groundbreaking book The Americans.

Here’s what I asked students in my “Contemplation and Imagination” class to do:

1. Look at the photo projected on the screen.

2. Close your eyes and visualize, in as much detail as you can, the photo.

3. Look at the photo again. See if you notice anything new.

4. Close your eyes, paying attention to physical sensation.

5. Sketch the photo. (The projector is turned off.)

6. Look at the photo again.

7. Compose a written sketch of the image. (The projector is turned off.)

After this, I invited the students to talk about their experiences of the exercise. One soft-spoken student said, “the word wood to describe the desk—it misses so much.”

Yes, I thought, it’s inadequate, reductive. Lost is the grain. Lost are the shades of lighter and darker wood. It’s why translating sensory experience into language that retains at least some of the texture, complexity, and nuance of physical sensation is so hard.

On my drive home from class that night, I thought: language, whatever else it says, it always says, I sing of loss, I mourn.

I am what is missing.

For the first time in many years (twenty? thirty?), I think of Mark Strand’s poem “Keeping Things Whole.” It begins:

In a field

I am the absence

of field.

This is

always the case.

Wherever I am

I am what is missing.

When she wrote “wooden desk,” did my student think oh, my, there’s so much missing?

“The higher goal of spiritual living is not to amass a wealth of information, but to face sacred moments,” writes Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel in The Sabbath.

Maybe she, my student, experienced the disappointment, the despair that comes from losing “a wealth of information” as she tried to preserve in words what she had seen.

“Little we see in Nature that is ours,” writes Wordsworth.

Still, we see. When we are astonished by what we see, when we are shaken, uplifted, wounded, comforted by what we see, the astonishment, the anguish, the joy, the relief we experience is ours. We experience it deeply as ours.

Then we try to tell it, but the words are inadequate. They fail to convey to others what is, alas, unbearably ours and ours alone.

But this is not what troubles Wordsworth in “The World Is Too Much With Us.”

“We have given our hearts away,” he writes, to “getting and spending,” manufacturing and consuming. (As then, 1806, now?)

Where might we turn to have our hearts returned to us? Nature.

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers

Wordsworth gives us nature—intimate, vulnerable, vital—only to show how it has withdrawn from us or, as he writes in the next two lines, how we have become alienated from it.

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not.

Numb and suffering the acute pain of the loss of his tuneful bond with nature, Wordsworth cries out sharply,

Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn

Exposed, raw, and at once vulnerable and strong, Wordsworth is nowhere more present in this poem than here: “Great God! I’d rather be / A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn.”

But he isn’t a pagan, and his anguish is addressed to God.

And he doesn’t turn from the lea, the very spot from which he sees and hears the sea and suffers the absence of feeling, the loss of what he once felt in nature.

Sonic patterning: that’s one way a poet tries to make up for the poverty of language, its inherent inability to express the fullness of sensory experience. Just listen to the repeated and modulated sounds running through the few passages of Wordsworth I quoted above. (Go ahead, scroll back up, and read those passages aloud.) Say and feel in your mouth the fullness of this line alone: “A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn.”

Metaphor, or, more broadly, comparisons: that’s another way. Kenneth Koch, in Making Your Own Days: The Pleasures of Reading and Writing Poetry, says this about “comparisons”:

A comparison not only compares things but brings in more of the world. Explanatory sentences tend to restrict and even to reduce the amount of reality in what is being said; poetry, with its comparisons, expands it.

Thus, that seductive sea, that lustful, raging wind “up-gathered now like sleeping flowers.” How impoverished would the poem be if the sea were merely moonlit, the wind merely blowing all night, and both seemed distant and small and made little impression on the man on the lea.

I’m not a good writer. I don’t like writing. That’s what she could have thought, my student, when she looked up at Frank’s photograph and down at her written description of it.

I don’t know if she thought that. I know only this: she experienced loss in the classroom that night, and she was courageous enough to share her experience with the rest of us.

Those other thoughts—I’m not a good writer; I don’t like writing—arise immediately after experiencing loss, to “protect” us from repeating the mistake that made us feel bad in the first place: writing.

The rest of Strand’s poem:

When I walk

I part the air

and always

the air moves in

to fill the spaces

where my body’s been.

We all have reasons

for moving.

I move

to keep things whole.

“There is nothing as whole as a broken heart,” says the Kotsker Rabbi.

Writing: it breaks your heart to make it whole.