Give them rest, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine on them. The just will live in memory everlasting and will not be in fear of ill report.

Give them rest, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine on them. The just will live in memory everlasting and will not be in fear of ill report.

Thus begins the Solemn Requiem Mass that some Roman Catholics say on All Souls’ Day, when the Church prays for the dead. Historically, the Catholic tradition grew from a Jewish practice first performed after a battle described in the Second Book of Maccabees.

According to the Maccabean story, so many faithful soldiers perished in the fray that their leader Judas fretted for their souls. Desiring to atone for their sins and ensure their resurrection, he took up a collection, amassing two thousand silver drachmas, which he sent to Jerusalem. In a similar way, modern Catholics combine their prayers, hoping to expiate sins and usher souls from purgatory to heaven.

While the custom of praying for the dead is ancient, there was no official Catholic celebration until late in the tenth century, when a French pilgrim returning from the Holy Land was shipwrecked on a craggy island. There he met a hermit who told him of a chasm in the rocks through which continuously rose the groans of the suffering souls in purgatory.

From the fissure also erupted the intermittent curses of the demons that supervised the dead. These devils reviled the monks of Cluny, France, whose prayers were especially potent and were depleting purgatory’s ranks.

Prompted by the hermit, the pilgrim hurried off to Cluny and begged the abbot and brothers there to redouble their supplications so every soul in purgatory could stop suffering and pass to paradise. Thus, the second of November became All Souls’ Day, an annual day of prayer, a custom that spread throughout France and Europe, reaching Rome in the fourteenth century.

My church, Blessed Sacrament in Seattle, celebrates each All Souls’ Day with a Solemn Requiem Mass according to the Dominican Rite. The Mass is said at night in Latin and includes Dominican chanting and polyphonic hymns.

A black casket is placed upon the altar surrounded by six man-tall candles that burn throughout the rite. Inside the otherwise-empty coffin are the names of the parishioners’ deceased, hundreds and hundreds of names, among them those of my parents and grandparents and many others I have loved.

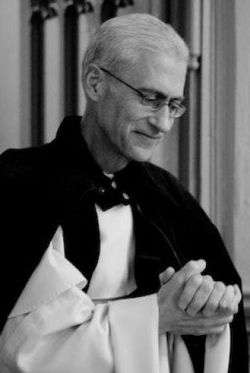

Also among the names is that of a priest, Father Tom Kraft. Tall, with salt-and-pepper hair, a jack-o-lantern smile and deep gray eyes, he said all the Masses I attended when I first joined the church. Every single Sunday, he talked and sang of God and placed communion in my hands with a grace that moved me greatly.

Still, I never said a word to Father Tom until his last second of November, when I wrote him a letter. Now, on every All Souls’ Day, I pray to always say I love you to the living, not wait to pray for the dead.

November 2, 2008

Dear Father Tom—

If I had a magic wand, I would wave it and there would be peace, and no poverty or illness, and you would be well.

But I don’t have a magic wand, which is why I started going to Blessed Sacrament the week after Easter this year, after a thirty-year almost-total lapse in church attendance. I chose Blessed Sacrament because I liked the bricks and steeple, and it’s close enough to walk there from my house.

What I found at Blessed Sacrament was more than bricks. I found music so soulful I ache, stained glass so lovely I fly, and a sweet, consistent community that sounds like they mean it when they shake my hand and wish me peace. They look right into my eyes and I look back.

I also found you, a priest who smiles and glows from the altar, like the prayers, songs, readings, and community all really mean something, and like God is actually up there, or even better, down here with us. And when I walk home each Sunday, the sky and flowers and leaves somehow seem more vivid, and the homeless make me bleed even more than they usually do.

It’s probably for this reason that I thought of you a few weeks ago. My son Sean is a sophomore in college who will defend just about anyone, regardless of race, ethnicity, social status, or sexual orientation. The only people he doesn’t understand are those with religion.

As far as Sean can tell, God is an excuse for committing atrocities who allows people to go to church on Sunday, then spend the remainder of the week denigrating Arabs, Latinos, Asians, African-Americans, the poor, the disabled, and gays. To my son, religion is a show without interiority.

This, I think, was one of many reasons that the recent death of Sean’s friend Luke shattered Sean as it did. Luke was a good, caring person, and Sean kept on repeating that Luke didn’t deserve to die at age nineteen. Sean also didn’t want to believe that he’d never see his friend’s face again or hear his voice.

So I wished I could send Sean to you because I had a feeling you could open a window that would enable him to hope that someday he would see Luke, and maybe even God.

I didn’t know when Luke died—I didn’t know until today—that you are fighting cancer, or that you have a CaringBridge blog-site with 911 letters and almost 25,000 hits, all expressing the same prayer—that you go on glowing from the altar. I can’t predict the future, but I know one thing for sure, one way or another you will.

I miss you, Father Tom.

Jan Vallone is the author of Pieces of Someday, a memoir, which won the Reader Views Reviewers Choice Award and will be re-released in fall, 2013. Her stories have appeared in The Seattle Times, Catholic Digest, Guideposts Magazine, English Journal, Chicken Soup for the Soul, Writing it Real, and Curriculum in Context. Once a lawyer at a large law firm, and later an English teacher at a tiny yeshiva high school, she now teaches writing and literature at Seattle Pacific University.