I’ve had a few nasty discoveries of late. All too often, I’ve found out that things I’ve always valued are considered to have very little value in the estimation of the going market. They’re just not worth as much as I’d believed.

I’ve had a few nasty discoveries of late. All too often, I’ve found out that things I’ve always valued are considered to have very little value in the estimation of the going market. They’re just not worth as much as I’d believed.

“And why the hell not?” I’ll ask, irked, when given the dismissive news by financiers, appraisers, auctioneers, and agents—anybody whose expertise I’ve called upon for a valuation.

It doesn’t sit well, disillusionment—especially when you think the rest of the world has got it all wrong, and when you’d been counting on their tastes to be in line with your own.

So I wasn’t in the mood for more of the same the other day, after I went to The National Gallery of Art’s new exhibit on Andrew Wyeth. I like Wyeth very much, and after seeing the works—wonderful, evocative renderings of various portals in the farmhouses that he memorialized around his Maine landscape—I did a little research to learn more about some of the images.

Lo and behold, turns out Andrew is a favorite whipping boy of the modern art scene.

Not only is he disfavored, he’s considered a “kitschmeister.” To my shock and dismay, I learned his work is often called “tired” and “overwrought”; “a cold gimmick.” His eschewing of abstraction—the preferred mode of the cognoscenti for nearly a century—and his vast popularity have made him the kind of artist you’re not supposed to like. Nowadays, he’s akin to Hemingway (whom I also appreciate), and Steinbeck (yep), and Frost (ditto). Admitting an admiration for them is like taking off your shoes at the dinner table—you reveal yourself quite clearly.

Well, all right then. Here I am, barefoot—and pass the ketchup.

I’m not trying to be a populist antagonist, but I don’t see that rarity of opinion is the litmus test for artistic achievement.

I understand the criticism of art that doesn’t have any tension in it, the kind that’s meant for calling cards, jigsaw puzzles, and wall posters (but then I don’t think people who paint such matters actually contend that what they’re doing is profound, so the criticism is unfair), but that’s hardly what’s going on in these paintings. I also bridle at the idea that if something’s accessible, it’s somehow discount-worthy.

Probably what these critics find so distasteful is the fact that Wyeth is capable of interpretation. Wary of committing the effective fallacy, I do actually feel something when viewing his work. Anyhow, that fallacy is intended to caution against claiming a work is only what it makes you feel; it’s not intended to banish feeling altogether or to discredit its role in a work’s achievement.

I also think that the art world has a kind of clubby establishment that favors whatever confuses and dispossesses. To them, seriousness equates to the claustrophobic and morose. The more people that “get” the work, the less fun it is to scoff at them.

The thing is, although Wyeth is stark and somber, even sad much of the time, he’s not really depressing. There’s an ironic lambency in his paintings, like the stoic beauty of Shaker furniture, lit by the fragile light of a quiet winter afternoon. There’s even a note of abstraction in his efforts, as a friend pointed out—the houses and windows are Mondrian boxes, washed of color (but infinitely more interesting for their depth).

And why is Wyeth charged with aloofness when Edward Hopper, who shares cold landscapes and subject matter, is not? Maybe it’s because there is so little hope in Hopper’s work. He seems to confirm the spirit of the age (and I like Hopper, by the way).

Not so with Wyeth: he says he loved the windows so much because they held within them the spirits of those who stood there, passed by there—the portals between the domestic and the wild, between the manufactured and the natural, the places where we linger, caught between the worlds, at a junction that is both harbor and exposure.

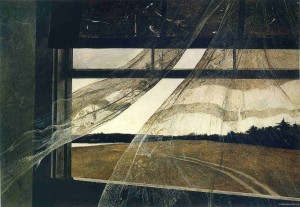

The Gallery exhibit is anchored by what Wyeth considered one of his best works, Wind from the Sea, which was inspired by a visit made to the farmhouse of his friends, Christina and Alvaro Olson. Christina was the polio-stricken woman whose nobility Wyeth immortalized in Christina’s World, and her house was the staging ground for much of his art. Wyeth said of this image:

I walked up into the dry, attic room one day. It was a hot summer day in August, so hot that I went over to that window, pushed it up about six inches and as I stood there, looking out, all of a sudden this curtain that had been lying there stale for years, God knows how long, began slowly to rise, and the birds crocheted on it began to move. My hair about stood on end. So I drew in very quickly and incisively and I didn’t get a west wind for a month and a half after that either. I did many drawings for it because I was so moved by that sudden thing.

The curtains evanesce before the window, fading to nothing in the far left; ghost birds dance upon the wind that undulates the fabric upon which they lie. The place beyond that, like any vista that we behold from afar, beckons to our hopes and directs our intentions. What sight, be it street, ocean, or valley, does not cast us off, launch us out from the place behind our eyes and ferry us forth across the view. It’s why we climb high, why we want to see out.

So when it comes to Wyeth, count me in. I’m on his side. My granddaddy’s shotgun may not be the deposit of worth I thought it was, and my silver dollars aren’t going to let me retire early, but when it comes to what a masterpiece is, I’ll trust my own scales to do the weighing.

A.G. Harmon teaches Shakespeare, Law and Literature, Jurisprudence, and Writing at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. His novel, A House All Stilled, won the 2001 Peter Taylor Prize for the Novel.

Image Used: Wind From The Sea, 1947 by Andrew Wyeth