Continued from Friday

Continued from Friday

In order to start treating being an artist more like a job and less like some precious ritual, an alternative lifestyle that non-artists don’t understand, I have done a lot of reading about how people throughout history have defined art and artists.

For hundreds of years, there has been contentious discussion about who can be called an artist. For example, for many years potters, weavers, carpenters, and sculptors of religious or ritual statuary were not considered artists because what they made was useful: if I can drink out of it, carry things in it, or wield it in some way, then it is not art but a tool.

On the other hand, the term artist has always been connected to the magical—the creation of something from within, like a poem or a melody, or the transformation of one substance to another more valuable one (alchemists were known as artists). Based on this definition, up until the Renaissance, painting was not recognized as one of the arts because it was seen as merely decorative—used to adorn and gild, rather than as a medium for the creation of something new.

Leonardo da Vinci took great offense at this, and tried to make his case by attacking poetry as an inferior art because it merely appealed to the ear, whereas the painting appealed to the eye “by true likeness.”

“Take a poet who describes the beauty of a lady to her lover and a painter who paints a picture of her, and you will see to which nature will turn the young lover.”

However, in making an argument for painting as an art, and the highest one at that, his description of the painter at work introduced representations that have shaped the way the public has viewed the labor of the artist ever since.

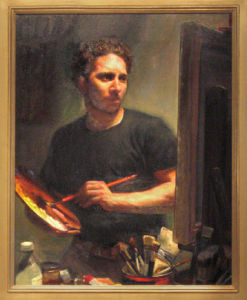

Da Vinci writes that the painter sits “at great ease” before his work wielding an instrument much lighter than the hammer and chisel of the sculptor. Furthermore, unlike the poet or sculptor, the painter works with “attractive colors” and because he need not worry about getting dusty and dirty, he is free to be “adorned with such garments as he pleases,” and, “his dwelling is full of fine paintings and is clean and often filled with music or the sound of different beautiful works being read, which are often heard with great pleasure, unmixed with the pounding of hammers.”

Given the connection between work, virtue, and moral uprightness in the Protestant work ethic we can begin to see why it may have taken so long for art-making to be considered work.

By comparison, the artist’s labor is seen as lacking rigor and too oriented toward pleasure to be spiritually sustaining. It is also interesting to note how the description, written sometime in the mid-sixteenth century, captures the salon culture that would typify bohemias in Europe and the United States over three hundred years later.

By the time Jacques Maritain was writing the essays in Art and Scholasticism—one of the most influential works of modern theology on art-making—only one hundred years had passed since Paris’ bohemian heyday. For Maritain, whose wife was a poet and whose friends included Marc Chagall, Georges Rouault, Georges Bernanos, and Jean Cocteau, there was little debate that the artist should be considered a worker—or, rather, should consider himself a worker.

Maritain believes that the artist is chiefly concerned with making, not knowing; that too much self-consciousness can kill the art. He worries: “the artist if he is not to shatter his art or his soul, must simply be as an artist what art wants him to be—a good workman.” By saying that this is what art wants, he is locating the good of art outside of the artist, a movement away from seeing art as being expressed through individual wills and selves, a move which represents a turning away from the caricaturized bohemian ideal of the artist as Byronic hero whose personal style and predilections are just as integral to his art as his method.

As a Frenchman born in the late nineteenth century, Maritain was no doubt aware of la vie boheme and its vagaries, especially what Jerrold Seigel describes as the “cult of self” that emerged, which called for salvation through descent into the libertine lifestyle epitomized by the likes of Rimbaud and Baudelaire. Maritain laments:

The modern world, which has promised the artists everything, soon will scarcely leave him even the bare means of subsistence. Founded on the two unnatural principles of the fecundity of money and the finality of useful, multiplying needs and servitude without the possibility of there ever being a limit, destroying the leisure of the soul . . . imposing on man the panting of the machine and the accelerated movement of matter . . . is imprinting on human activity a truly inhuman mode and a diabolical direction, for the final end of all this frenzy is to prevent man from resembling God.

Upon re-reading this passage from Maritain, I’m ashamed to say I skipped over all of the meaty parts about the unnatural principles of capitalism. I completely forgot about my earnest mission to treat my art as work, because I couldn’t get the image out of my head of God checking his Facebook page.

I imagined—and here I will reveal just how deep and complete my addiction to social media is, how deluded it has made me—God irritated by how many of his friends were posting pictures of the organic meals they had prepared, the messy state of their writing desks, or the cute poses their pets fell asleep in, and then finally coming upon something I posted—a quote from Flannery O’Connor or a link to a blog post I had written—and thinking, “Now this is why I still use Facebook.”

David Griffith is the author of A Good War is Hard to Find: The Art of Violence in America (Soft Skull). He teaches creative writing at Sweet Briar College in Virginia where he lives with his wife Jessica Mesman Griffith and children, Charlotte and Alexander. His essays and reviews have appeared in Image, Utne Reader, The Normal School and online atkillingthebuddha.com. He blogs at Pyramid Scheme.