(Continued from Part 1)

In 1983, the celebrated Southern Catholic writer Walker Percy wrote a satirical self-help book, drawing readers in with his usual charm and wit, but leading us to serious questions on life’s meaning and the uniqueness of our existence. Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book explores our place in the universe, making us look at those things that make us human. Percy is not afraid to make us look at those things that we’d rather just not bother with:

Why is it that the look of another person looking at you is different from everything else in the Cosmos? That is to say, looking at lions or tigers or Saturn or the Ring Nebula or at an owl or at another person from the side is one thing, but finding yourself looking in the eyes of another person looking at you is something else. And why is it that one can look at a lion or a planet or an owl or at someone’s finger as long as one pleases, but looking into the eyes of another person is, if prolonged past a second, a perilous affair?

Why is it so hard to truly be in the recognition of another? Fully in the presence of another? Does it take me out of the TV show of which I’m the star? Whether it’s a comedy or tragedy or whatever, at least I’m the star. But like Truman Burbank, the lead character in the film The Truman Show, whose life, unbeknownst to him, is one big staged reality TV series, don’t I eventually catch on at some point, don’t I catch on to what I maybe always knew was true? My little world cannot actually be all there is. My show has grown tired. Walker Percy lays out the existential pattern that fluctuates between the mundane and transcendence.

Is This the Best of All Possible Worlds?

Like Truman and Lagerkvist, if I’m told there’s nothing more, then why do I want something more? Percy cites Mother Teresa’s observation, that wealthy Westerns suffer from a great spiritual poverty. “The impoverishment of the immanent self derives from a perceived loss of sovereignty to ‘them,’ the transcending scientists and experts of society. As a consequence, the self sees its only recourse as an endless round of work, diversion, and consumption of goods and services.” Over and over the cycle goes, hit the mark just enough to buy into another round. This is life, I guess? “Failing this and having some inkling of its plight, it sees no way out because it has come to see itself as an organism in an environment and so can’t understand why it feels so bad in the best of all possible environments.” Like Voltaire’s Pangloss in Candide, stubbornly saying this is the best of all possible worlds, this is it, cultivate that garden and mute your heart when it gets too loud, why then does Hemingway’s old man drink alone, mocking a God he doesn’t believe is there to fight off a crushing despair?

Transcendence by Varying Means and Degrees

Percy explores the desire for transcendence, the exhilarating encounter with truth and beauty, wonder and awe, as can be touched in various human experiences and vocations, but cannot seem to sustain itself. The modern person, Percy outlines, has a handful of options we tend to use to ease the fall back into the world, which he calls the problem of reentry. The fact that the options exist and are frequently utilized reveals that our hearts cannot help but desire and seek transcendence, even in the mundane. He poses, “How do you go about living in the world when you are not working at your art, yet still find yourself having to get through a Wednesday afternoon?” In general, the options look like this according to Percy:

Options of reentry into such a world are: (1) reentry uneventful and intact [the everyday and transcendent coexist–rare], (2) reentry accomplished through anesthesia [e.g. alcohol], (3) reentry accomplished by travel [to move and move some more, e.g. Hemingway and Kerouac], (4) reentry accomplished by travel [sexual], (5) reentry by return [turn around and go home–hometown], (6) reentry by disguise [play another part until it becomes true, e.g. urban cowboy might become a real cowboy], (7) reentry by Eastern window [self-negation, Eastern religions], (8) reentry refused, exitus into deep space [suicide], (9) reentry deferred [withdraw, hermitage], (10) reentry by sponsorship [life before and for God], (11) reentry by assault [activist or “lonely radical”]

The Self–Vulnerable, Before God

Percy asks us to score ourselves based on how attractive each option presents itself as. Put in your own 21st-century items under one of the categories, and feel free to spend some time scoring yourself, but the focus here is on option 10 (conversion):

Reentry under the direct sponsorship of God. It is theoretically possible, if practically extremely difficult, to re-enter the world and become an intact self through the reentry mode Kierkegaard described when he noted that “the self can only become itself if it does so transparently before God.” This is in fact, according to both Kierkegaard and Pascal, the only viable mode of reentry, the others being snares and delusions.

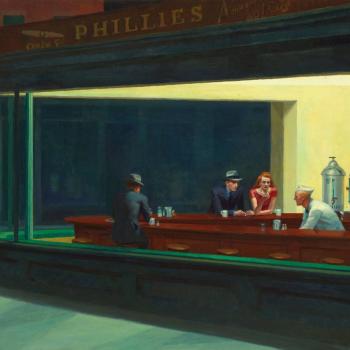

The old man at the counter of that clean, well-lighted place has chosen anesthesia, among other things; for instance, a failed attempt at option 8, reentry refused (suicide). He shares Larkin’s “special way of being afraid,” that “No trick dispels. Religion used to try,” as he mocks a hole through the words that were supposed to give him comfort. One cannot concoct an encounter with the transcendent, but that is what’s needed. Not a form of reentry to keep away the despair of nothingness, but a vulnerable heart and a will to be humbled, corrected, wrong, embraced, shown mercy, restored before the One who gave you the very desire for the transcendent and fullness in heart to begin with.

Despair darkens possibilities and wants mostly to remain in itself, crushed by the weight of nothingness, but strangely comforted in being subject to nothing by one’s own despair, a familiar horror that one understands well. The world is limited to one’s understanding. It is bleak, as Larkin so brutally and poetically lays out, but it is at least my own. For Søren Kierkegaard, in his classic philosophical work, The Sickness Unto Death, this is edging closer to faith in a way:

The decisive thing is, that for God all things are possible. This is eternally true, and true therefore every instant. This is commonly enough recognized in a way, and in a way it is commonly affirmed; but the decisive affirmation comes only when a man is brought to the utmost extremity, so that humanly speaking no possibility exists. Then the question is whether he will believe that for God all things are possible—that is to say, whether he will believe. But this is completely the formula for losing one’s mind or understanding; to believe is precisely to lose one’s understanding in order to win God.

What’s a Man to Do?

To reach the end of one’s own understanding, to finally turn outward from oneself, beyond the world and the cosmos, and ask with Lagerkvist, “Who are you that fill my heart with your absence? Who fill the entire world with your absence?”; that is really the beginning of faith. This becomes the most honest position, the only one that lets the Mystery remain a possibility and places itself before it. As Kierkegaard continues, “The opposite of being in despair is believing;[…] by relating itself to its own self, and by willing to be itself, the self is grounded transparently in the Power which constituted it.” This is the turnabout that allows one to confront those desires, the ones that frustrate us because they seem to impossibly desire the infinite, is the first step out of despair.

The old man keeping his despair at bay in the diner should not begrudgingly and forcefully mumble through the proper words of the prescribed prayers as an anaesthetic. He should fall to his knees with all his despair and a vulnerable heart that allows the infinite Mystery to penetrate his being, even for a moment. He needs to allow himself to recognize that profoundly simple premise, that he did not create himself, and that his loneliness is a sign of his detachment from and longing for his Creator. The existential response is to allow room for and to stay in front of this Presence. The one that starts to salve the painful longing of the heart that absence wounds. He needs to sit in the Silence, which is indeed something. To slow down enough to listen, to quiet the nada nadas, and hear that the beating of his heart is an echo of the voice of Him who responds to his cry.

Note: This post originally appeared in full in Solid Food Press Literary Journal (Oct. 23, 2023).