Moses was a Hebrew, but was raised in Egypt’s royal family as the grandson of Pharaoh. His revulsion against the injustices the Hebrews suffered erupted into a lethal attack on an Egyptian man who he found beating a Hebrew slave. This act came to Pharaoh’s attention, so Moses fled for safety and became a shepherd in Midian, a region several hundred miles east of Egypt on the other side of the Sinai Peninsula. We do not know exactly how long he lived there, but during that time he married and had a son. In addition, two important things happened. The Pharaoh in Egypt died, and the Lord heard the cry of his oppressed people and remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Ex. 2:23-25). This act of remembering did not mean that God had previously forgotten about his people. It signaled that he was now about to act on their behalf. For that, he would call Moses.

Moses was a Hebrew, but was raised in Egypt’s royal family as the grandson of Pharaoh. His revulsion against the injustices the Hebrews suffered erupted into a lethal attack on an Egyptian man who he found beating a Hebrew slave. This act came to Pharaoh’s attention, so Moses fled for safety and became a shepherd in Midian, a region several hundred miles east of Egypt on the other side of the Sinai Peninsula. We do not know exactly how long he lived there, but during that time he married and had a son. In addition, two important things happened. The Pharaoh in Egypt died, and the Lord heard the cry of his oppressed people and remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Ex. 2:23-25). This act of remembering did not mean that God had previously forgotten about his people. It signaled that he was now about to act on their behalf. For that, he would call Moses.

God’s call to Moses came while Moses was at work. The account of how this happened contains six elements that form a pattern evident in the lives of other leaders and prophets in the Bible. It is instructive to examine this call narrative and to consider its implications for us today, especially in the context of our work.

First, God confronted Moses and arrested his attention at the scene of the burning bush (Ex. 3:2-5). A brush fire in the semi-desert is nothing exceptional, but Moses was intrigued by the nature of this particular one. Moses heard his name called and responded with the expression, “Here I am.” This was a statement of availability, not location.

Second, the Lord introduced himself as the God of the patriarchs and communicated his intent to rescue his people from Egypt and to bring them into the land he had promised to Abraham (Ex. 3:6-9).

Third, God commissioned Moses to go to Pharaoh to bring God’s people out of Egypt (Ex. 3:10).

Fourth, Moses objected (Ex. 3:11). Although he had just heard a powerful revelation of who was speaking to him in this moment, his immediate concern was, “Who am I?”

In response to this, God reassured Moses with a promise of God’s own presence (Ex. 3:12a).

Finally, God spoke of a confirming sign (Ex. 3:12b).

These same elements are present in a number of other call narratives in scripture, for example in the callings of Gideon, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and some of Jesus’ disciples. This is not a rigid formula, for many other call narratives in scripture follow a different pattern. But it does suggest that God’s call often comes via an extended series of encounters that guide a person in God’s way over time.

|

Gideon |

The prophet |

The prophet |

The prophet |

Jesus’ Disciples |

|

|

Confrontation |

6:11b-12a |

6:1-2 |

1:4 |

1:1-28a |

28:16-17 |

|

Introduction |

6:12b-13 |

6:3-7 |

1:5a |

1:28b-2:2 |

28:18 |

|

Commission |

6:14 |

6:8-10 |

1:5b |

2:3-5 |

28:19-20a |

|

Objection |

6:15 |

6:11a |

1:6 |

2:6, 8 |

|

|

Reassurance |

6:16 |

6:11b-13 |

1:7–8 |

2:6-7 |

28:20b |

|

Confirming Sign |

6:17-21 |

1:9-10 |

2:9-3:2 |

Possibly the |

Notice that these callings are not primarily to priestly or religious work in a congregation. Gideon was a military leader, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel were social critics, and Jesus was a king (although not in the traditional sense). In many churches today, the term “call” is limited to religious occupations, but this is not so in scripture, and certainly not in Exodus. Moses himself was not a priest or religious leader (those were Aaron’s and Miriam’s roles), but a statesman and governor. (For more on calling to non-religious work, see “What Does It Mean to be Called?”)

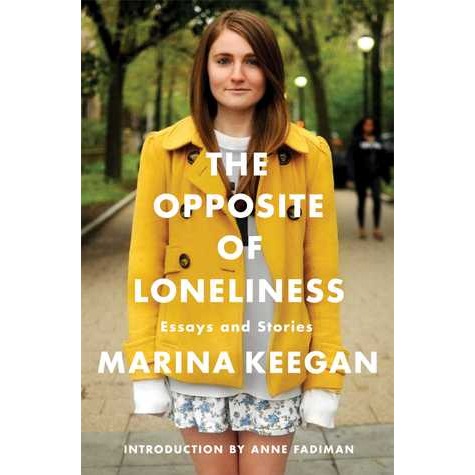

Adapted from Theology of Work Project. Image: “The Bronze Serpent,” anon, ca. 1600. Courtesy of the Grohmann Museum.