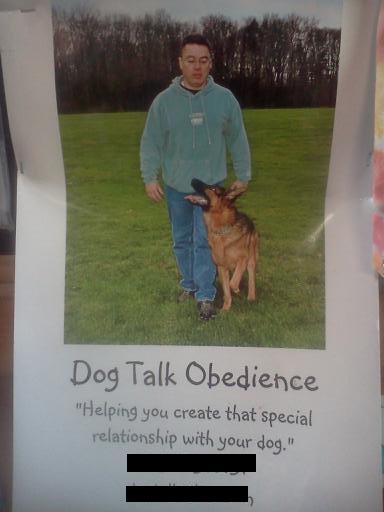

I was coming out of our local natural food store yesterday when I saw this poster hanging on the community bulletin board. Something didn’t seem right about the picture so I stood for a moment looking at it – and then I saw it. Look closely. The dog is wearing a prong collar.

Newsflash: if the trainer could actually “talk” dog or had a relationship with his dog, it wouldn’t need to be on a prong collar.

I’m an amateur student of dog behavior and communication – and when I say amateur, I mean that don’t have a certificate in dog training. However, I’ve done my homework. In addition to many, many classes I’ve done with my own dogs I have, over the last several years, read dozens of books on dog genetics and behavior, dog anatomy, animal communication (including the required reading for an MIT Openware class on animal behavior). I’ve shadowed local dog trainers and am part of a positive methods dog training group, even though I am not an actual dog trainer. (UPDATE: In other words, I surround myself with constantly updated resources. I don’t want to give the impression that I’m an expert … )

But because of the research I’ve done, I’m always alert when dog trainers talk about having relationships with their dogs, or who use phrases like “dominant/submissive”, or who promote themselves as positive dog trainers.

Some of them have their heads up their … um … tails.

The prevailing dog training culture for many decades centered on methods that used correction (ie: yank the dog hard to get its attention) and promoted the pack mentality of “being your dog’s leader”.

Problem is that almost all of that information is wrong. And we know that because we have updated research – legitimate, scientific research along with discoveries in genetics that give us better understandings of how dogs think and communicate as well as what they’re all about genetically.

Take for example the whole “pack leader” mentality. Once upon a time, trainers taught owners that in order to make your dog behave, you had to let the dog know you were the leader with alpha rolls, snarling and other aggressive, in-your-face communication. That was based on observations of wolves in captivity, where the wolves appeared to always be vying for the leadership position. Trainers took those observations and applied them to dogs and their owners. Everyone thought that dogs were simply tame wolves, so it made sense (at the time).

The problem is that once more sophisticated methods of observation were developed, technology that let us view, record, and study wolves in the wild and in their natural pack formations, we learned that what happened with wolves in captivity wasn’t really what happened in the wild.

Wolves in a pack in nature – a mother, father, offspring from several generations – behaved very much like a human family. Yes, the mother and father led, but at various times the everyone had their role. Juveniles cared for younger siblings, mothers took charge in situations where her skills were needed. There was not constant vying for leadership. There was not a linear hierarchy but a much more circular hierarchy.

There was cooperation. There was group problem solving. Yes, there was fighting but almost always when members of another pack invaded.

We began to realize that we got a lot of important stuff very wrong. Take that “submissive” belly up pose, which we used to think meant “I’m just being nice to you until you show a weakness and then I’m going to take you down”. Trainers taught that owners were supposed to “roll” the dog onto his back to show him who was “alpha”, teach him who’s boss, make him submit. Now that we’ve got more research done in actual wolf pack situations, it seems as if that the “belly up” pose (which simply defines the look, not the meaning) is a rare occurance in nature but happens much more frequently in captivity, where wolves who are not of a natural pack are forced to live together in an unnatural pack environment.

In his book, Dog Sense, author John Bradshaw writes:

“When observed in zoos, it is most likely to be performed by wolves that are on the fringes of the captive ‘packs’, are often involved in fights, and rarely participate in group howls. These are the very wolves that would almost certainly have gone off on their own if the fence surrounding their enclosure hadn’t been there. Continually stressed by being forced to remain in close quarters with other wolves that threaten to attack them at every turn, these outcasts will try any tactic that might deflect aggression.”

Translation: Your dog wasn’t being submissive because he respected you; your alpha roll had scared the bejeepers out of him. Looks like we’d been training our dogs as if they were our enemies instead of our beloved family members.

Not to mention the fact that dogs aren’t domesticated wolves any more than humans are talking apes, so treating them as such was far, far off the mark. In fact, recent science has determined that, genetically, dogs are most likely descended from a jackel than from the wolf we think of today. That opens up a whole other discussion about dog genetics and behavior.

But back to this poster.

If the relationship this trainer has requires the dog to be threatened with pain in order to obey, that’s not a relationship. That’s cohersion.

Yes, folks, it is possible to train a dog without prong collars, shock collars, choke chains, amd “corrections” like yanking and pulling. There is no place at all in modern dog training for alpha rolls, grabbing your dog by the scruff of his neck or screaming in his face. Yes, you can take a reactive, very difficult dog and with lots (and lots and lots) of time and patience understand their fears and meet their needs.

I know, because I did it, with a very reactive pit bull mix. To say she was a difficult dog would be an understatement. But since we’d had her from 6-weeks-old (I brought her home from the shelter where I was volunteering and where she was headed directly to the euthanization room) failure was not an option.

How we did it would fill a book. We had to address issues of bad breeding, tension in the house due to the terminal illness of one of my dogs, and a whole slew of other issues that had humans and canines on edge 24/7. But I can tell you this with certainty: we didn’t use shock collars to address the problems. We didn’t use prong collars. We used more hot dogs and treats than you can imagine. We found ways to separate the dogs to decrease the tension. We worked with trainers whose methods I would use on my kids.

I studied and studied and then studied some more. I learned how to read a dog’s body language and “speak dog”. I learned what caused Bailey’s fears, learned how to help her become comfortable in those scary situations, and how to avoid making them worse.

We learned, for example, that one reason she completely freaked out whenever you tried to pet her was because she has mild hip dysplasia … in both hips … diagnosed at six months old. Simply put, sometimes her entire back end hurt. We addressed the pain, keep her exercised without overdoing it, and simply stopped trying to pet her in any other place than her chest and neck, both of which she solicits when she wants a little snuggle time. And this dog is a snuggler. Just don’t pet her back end.

A year ago Bailey was afraid of everything and everyone, and responded by jumping, biting and barking like a wild animal. I mean, a wild, wild, out of control animal. Yesterday, I took Bailey for a walk in the city – with cars and squirrels and people everywhere. She sat nicely at the curbs to cross the street and waited patiently for elderly people with walkers to pass us on the sidewalk. Completely new situation with lots of noise and activity, and she navigated it like a champ.

It can be done. (And here’s some video to prove it.)

A long time ago, I was the dog owner who used the choke collar, who used a shake can a few times to try to curb barking. I didn’t know any better. My vet recommended a trainer, I went and did what he told me to do. What I got was an anxious dog who obeyed commands … out of fear. It took years to undo what I’d done and for him to trust that every time I reached for a can of cola I wasn’t going to throw it on the ground to make him shut up.

I’ve done it the wrong way, and trust me, there is a right and better way.

When you’re looking for a trainer, make sure that you aren’t fooled by words like “positive” or “relationship”. Prong collars and shocking your dog into submission are not positive and don’t foster any kind of relationship you actually want. A trainer with a certificate from a dog training school often has less education that I have after my own years of study. They just have a piece of paper saying they completed some basic coursework.

Here are a few tips to keep in mind when you’re looking for a trainer:

1) Look for trainers who are constantly going to school, reading animal behavior journals, and studying up on current science and training methods to maintain the current industry standards of animal care. When they cite reasons for their training methods, check them out yourself. If they mention behaviorists like Ian Dunbar and Patricia McConnell (there are many others; those are just two that come to mind immediately), you’re on the right track. If they cite The Dog Whisperer as a resource … run in the other direction.

2) Never leave your dog with a trainer to do the work. Not only are you not privvy to the methods the trainer actually uses, you are missing the key component to training: working with your dog to build a relationship.

3) Don’t make your decision about a trainer based solely on phone calls to the trainer. Go to the training facility. Talk to all of the trainers, observe classes, talk to other dog owners, and most importantly, watch to see if the dogs are enjoying their time in class. If you see dogs on prong collars or hear the trainer talking about pack mentality, this is not the trainer for you or your dog.

4) If you’re having behavior problems with your dog, ask the trainer for an evaluation as well as a plan of action to address the situation. Get more than one opinion. You should be able to have clear information, clear instructions, consistancy in the plan and open channels of communication with a trainer who is looking at the problem from every angle and incorporating the entire family into the behavior modification process.

5) Check out one of my favorite dog training books for beginners, “Dogtown: A Relationship Manual for You And Your Dog”, from Best Friends Animal Society. I’ve read the book and compared it to the training methods of my favorite trainers. In this case, yes, what they’re teaching will lead to the relationship you want to build with your dog. If you’re new to training, find the whole thing a bit overwhelming or just want to learn some fun exercises to do with your dog, definitely get this book.

You can look for trainers in your area by contacting the Certification Council for Professional Dog Trainers and Pet Professional Guild.

UPDATE: I wanted to just add that just because a dog trainer isn’t listed with one of these organizations doesn’t mean they aren’t as qualified, experienced or up to date with current standards. Unfortunately, there isn’t any one place where you can get one list of qualified trainers who use humane, positive methods. That’s why you need to do your homework, ask questions, and pay attention to the little red flags.

RELATED POSTS: