![By Tomas Castelazo (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/637/2016/05/600px-Mary_and_joseph-300x240.jpg)

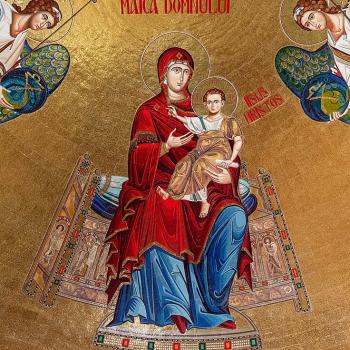

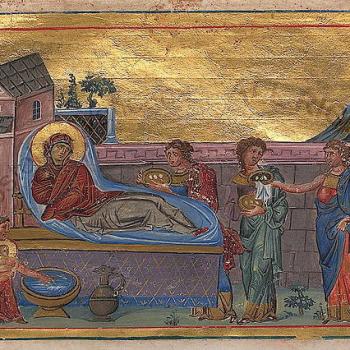

The promotion of virginity for those who have such a call does not hinder God’s command for humanity to be fruitful and multiply. Virginity and procreation represent two complementary callings, each good in and of themselves. In Mary, in the uniqueness of the virgin birth of Christ, the two come together as one, so that her virginity does not hinder but actually perfects her motherhood.[1] Her conception and birth of Christ our God demonstrates she is more fruitful than anyone else as she has given birth to the infinite, eternal God. What greater fruit can there be? What can even compare? Nothing. And yet, she continues to be fruitful as the spiritual mother of all Christians. All who are in Christ, all who are with Christ, have her as their mother: she is as fruitful as the kingdom of God, showing us how well she fulfilled the command of God.[2]

With all that said, we can return to the question at hand. How are we to understand Joseph and Mary as husband and wife? There have been two different ways this question has been answered. The complexities involved in both solutions can become and often are quite technical in theological manuals. Instead of going into such details, it is best to give broad outlines of the positions, which should be enough to understand how the question can be answered. The first possible solution, and normative in the East, is to say that they were husband and wife because those titles were bestowed upon them at their betrothal. The second, and the one which has become normative in the West, is to say they had all the blessings of marriage, confirming the validity of the marriage, even though there had been no consummation – consummation would then be said to be normative, but another, secondary way of validating marriage is possible if other conditions are met. The Western view is what led to the notion and development of so-called Josephite marriages (the name coming from St. Joseph).

The first way of engaging the question is founded upon the way betrothal was viewed upon in the ancient world as already fostering a kind of union with the couple, allowing them to be called husband and wife. Often this was a kind of legal realization with various expectations placed upon the couple. This is what we find in Scripture, wherein we find Mary and Joseph called husband and wife when they were betrothed. Joseph, when he learned of Mary’s pregnancy, is told to take Mary as his wife despite already being called her husband:

Now the birth of Jesus Christ took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child of the Holy Spirit; and her husband Joseph, being a just man and unwilling to put her to shame, resolved to send her away quietly. But as he considered this, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared to him in a dream, saying, “Joseph, son of David, do not fear to take Mary your wife, for that which is conceived in her is of the Holy Spirit; she will bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins.” All this took place to fulfil what the Lord had spoken by the prophet (Matt 1:18-22 RSV).

Betrothal in the ancient world was more than a mere promise of marriage, more than the way we view engagement today, but an actual change in status, so that those betrothed were often called husband and wife. This is why Scripture can and did call Joseph and Mary husband and wife during their betrothal. St Jerome noted this and said that while they were husband and wife, he did not consider them to be married:

[it] should not disturb anybody, as if she ceased to be betrothed because she was called a wife, when we realize it is the custom of Sacred Scripture to give the title of wife to those who are betrothed. Just as it is confirmed by the following testimonies from Deuteronomy: ‘If anyone,’ he says, ‘finds a damsel that is betrothed in a field and taking hold of her lie with her, he shall die; for he hath humbled his neighbor’s wife.[3]

Joseph, in this solution to the question, is the betrothed; he was given the duty to protect Mary and her honor, to treat her as his wife, to live like husband and wife in the sight of the world.[4] This duty was expressed by St. Romanos in his Hymn for the Nativity, wherein, speaking in the voice of Mary, he explained:

“I will tell you,” Mary said to the magi,

“why I keep Joseph in my house:

to refute those who slander me.

He will tell what he has heard about my Child.”[5]

Thus, there was the need for Mary to have someone there with her to protect her and her dignity. Joseph was chosen as “a witness to the conception without seed, and a helper in those events which were to be accomplished in accordance with the divine dispensation.”[6] If she married Joseph, she would have been under him, under his authority, as was the custom of the time. That would have put limits upon the freedom which had been given to her because of grace. And yet, that could not be, because she was meant to be above all such earthly authority:

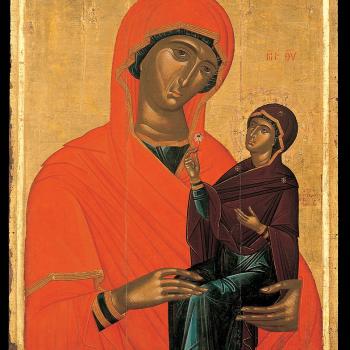

The Virgin is also duly called “Lady” in another sense, as she has the mastery of all things, having divinely conceived and borne in virginity the Master of all by His nature. Yet she is the Lady not just because she is free from servitude and a partaker of divine power, but because she is the fount and root of the freedom of the human race, especially after the ineffable and joyful birth. A married woman is ruled over rather than being a lady, especially after sorrowful and painful childbirth, in accordance with the curse of Eve: “In sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee” (Gen. 3:16). Freeing the human race, the Virgin Mother received through the angel joy and blessing instead of this curse…[7]

And so, it is said, they remained unwed, even if they were betrothed, allowing them to be called husband and wife. The expectations of marriage, that of consummation, therefore did not befall them. Joseph is “the betrothed” and Mary the “unwed bride,” indeed, her title as the “unwed bride” has a significant place in the Eastern tradition in the important Akathist Hymn, where he is constantly invoked with the words, “Hail, O Bride Unwedded!”

While a traditional explanation, the belief that Mary and Joseph were not truly married did not satisfy everyone. If the Holy Family is a special representation of the family, if they serve as an ideal which we should somehow imitate in our family life, how would this be possible if Joseph and Mary were not truly married? Many, especially in the West, believed they had to be seen as truly married, and so a different solution was sought. St. Augustine would give the foundation which the West would be able to use to establish its own answer: they had all the blessings, all the positive effects of marriage, and so truly were married, even if they did not consummate their marriage through conjugal union:

The entire good, therefore, of the nuptial institution was effected in the case of these parents of Christ: there was offspring, there was faithfulness, there was the bond. As offspring, we recognise the Lord Jesus Himself; the fidelity, in that there was no adultery; the bond, because there was no divorce. Only there was no nuptial cohabitation; because He who was to be without sin, and was sent not in sinful flesh, but in the likeness of sinful flesh, could not possibly have been made in sinful flesh itself without that shameful lust of the flesh which comes from sin, and without which He willed to be born, in order that He might teach us, that every one who is born of sexual intercourse is in fact sinful flesh, since that alone which was not born of such intercourse was not sinful flesh. Nevertheless conjugal intercourse is not in itself sin, when it is had with the intention of producing children; because the mind’s good-will leads the ensuing bodily pleasure, instead of following its lead; and the human choice is not distracted by the yoke of sin pressing upon it, inasmuch as the blow of the sin is rightly brought back to the purposes of procreation.[8]

Augustine recognized that betrothal made them husband and wife,[9] but then, because they were given a higher purpose in their marriage, he also believed that they received all the proper benefits of marriage and so could, and should, be seen as married. Consummation is ordinarily necessary to make a marriage complete because such activity “represents more perfectly the union of Christ and the Church.”[10] This union is, after all, what marriage is meant to symbolize. The fruit of the mystical union between Christ and the Church is normally demonstrated through the fruit of the marital union, that is, children. With the birth of Jesus, this purpose was fulfilled for Mary and Joseph, and so conjugal union was not necessary for their marriage. Another blessing of marriage is the grace which it gives to help a couple become holy through chastity.[11] Would any deny such grace is to be found with Mary and Joseph? Consummation was said to be the ordinary sign of that perfection, however, with the holiness of Joseph and Mary, no such sign is necessary, for they had the perfection of marriage, its end, without need of the sign (or, if there is a need for such a sign, there is no better sign than that of the virgin birth of Jesus).

This then should be seen as the background by which Blessed John Duns Scotus was able to explain how and why Mary, vowing virginity, could give herself in marriage to Joseph, to have a true and proper marriage, while never planning on consummating it:

In the marriage contract there is a mutual gift of bodies for carnal intercourse, but only under this implicit condition: namely, if it is requested. Hence, if both parties entering the marriage contract, immediately vow chastity, they are still truly contract. But this condition [viz. if you request it] does not preclude a vow of chastity, even where a contact of marriage exists, unless that condition is put into effect; therefore, where there is unqualified certitude it will never be put into effect, the contract of matrimony does not preclude a vow of chastity; but here there was such certitude. [12]

Here, Scotus suggested that Mary and Joseph truly gave the gift of their selves to each other, therefore establishing between them true married love with the proper bond of marriage, but that gift of the self included an acceptance of each other’s desire, that is, each other’s desire to forgo sex.[13] Therefore, it became suggested, if this was agreed upon, married union could be established in this special fashion.

Now, whether we follow the East’s declaration of Mary as “the unwed bride,” of the West’s designation that Mary truly was married, in either case, Mary’s virginity could be, and was, properly affirmed. The point behind both explanations was the same: Joseph properly protected Mary’s holiness. In either explanation, we see Joseph could be properly called Mary’s husband. Personally, I find the simplicity of the East’s explanation superior, however, I think Augustine was right in saying the proper goods of marriage were obtained by Mary and Joseph, even if we call them betrothed. And so it is possible to believe either they remained as unwed husband and wife, or as married husband and wife; in either case, they truly were husband and wife.

[1] There was a debate in patristic times as to what reproduction would have been like if humanity remained sinless. Some of the fathers pointed out that we were given sexual organs indicate that reproduction would have been the same, but would not be debased by lust, while others taught that Mary represented the kind of reproduction which would have occurred if there were no fall, that is, without use of sexual organs. While such speculation transcends our purpose here, it is worthy to note that some think Mary’s reproduction is more “natural” and our current mode of reproduction is not, contrary to the way we normally think of sexuality. St. Gregory of Nyssa, for example, believed that humanity could have reproduced in other ways. See St. Gregory of Nyssa, On the Making of Men in NPNF2(5):407. What this means is that the conception of Christ represented not an act contrary to nature, but its proper representation, even if other means of natural reproduction were also possible.

[2] And here, moreover, do other virgins find their fruit, in the spiritual heritage they leave behind.

[3] St. Jerome, “Against Helvidius” in St. Jerome: Dogmatic and Polemical Treatises. Trans. John N. Hritzu, Ph.D. (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1965), 14. St. Jerome gives further examples from Deuteronomy to justify his interpretation here, citing this passage of 22:24-5 with Deut. 20:7 and 22:23-4.

[4] Saint Jerome also said it was to make sure the world knew Mary was linked to the same lineage as Joseph for the sake of understanding the source of Jesus’s flesh. See St. Jerome, “Against Helvidius,” 15.

[5] St. Romanos, On the Life of Christ. Kontakia. trans. Archimandrite Ephrem Lash (San Francisco: Harper Collins Publishers, 1995), 7.

[6] St. Gregory Palamas, The Homilies. trans. Christopher Veniamin (Waymart, PA: Mount Thabor Publishing, 2009),102.

[7] ibid., 103.

[8] St. Augustine, On Marriage and Concupiscence in NPNF1(5): 269.

[9] See ibid., 268.

[10] Peter Lombard, The Sentences. Book 4: On the Doctrine of Signs. trans. Giulio Silano (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2010), 177. [IV-XXX.2]

[11] See for example, Raymond of Penyafort, Summa on Marriage. trans. Pierre J. Payer (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, 2005), 27.

[12] John Duns Scotus, Four Questions on Mary. trans. Allan B. Wolter, O.F.M. (Saint Bonaventure, New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2012), 85.

[13] See ibid., 89.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook:

A Little Bit of Nothing