He Did Not Have to Go Through Samaria

Note: This post does not continue from my last; I’ll be resuming that series shortly. This one is the usual weekly Gospel translation and commentary.

Samaritans observing Passover on Mount Gerizim

in 2006. Photo by Edward Karpov, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

The Gospel passage this Sunday was one of the Lord’s most beloved parables, that of the “Good Samaritan.” This stands out, because Samaritans appear only irregularly in the Gospels. Mark doesn’t mention Samaritans at all. Matthew barely touches on them—in chapter 10, when the Twelve are sent on their two-by-two missions, he records Jesus specifically excluding Samaria from their territory. The only significant part of John that deals with Samaritans is the scene at Sychar (4:4-42),1 though that forms the bulk of the chapter, and the “living water” motif (picking up from chapter 3 and continuing in later ones) is accented most in that text.

Interestingly, John says that to return to the Galilee, Jesus “had to go through Samaria,” which was not strictly true. It was perfectly possible to cross the Jordan into Peræa (the modern East Bank) close to Jericho, travel north for about fifty miles, and then cross back, up close to Beyt She’an (a.k.a. Scythopolis, since it was inhabited largely by Greeks as part of the Decapolis). It’d be annoying, and would add much more to your time and exertion traveling than you might suppose: The Jordan River valley is insanely deep, somewhere around three thousand feet lower than the Judean, Galilean, and Peræan countryside, so you’d have to add the trek down and back up again to your travel; but you could do that, if you wanted to. And given that i. you’re in for the fifty-mile journey north either way and ii. Jews didn’t share utensils with Samaritans (probably reflecting different interpretations of the purity codes), making it relatively inconvenient to maintain luxuries like “eating” during such a trip, I’m guessing Peræa saw a lot more Jewish travelers than it would have anyway.2

Saint Luc [St. Luke] (1894), by James Tissot.

Meanwhile, Luke takes a special interest in Samaritans. His is the only Gospel in which this parable appears, and his account of the Ascension in Acts specifies that the Church will bear witness to him in Samaria; they also come up “in person” on multiple occasions, spanning both Luke and Acts—see passages such as Luke 9:51-56, Luke 17:11-19, and Acts 8:5-25. Yet even Luke, in chapter 17, says that Jesus referred to the Samaritan who came back to thank him as ὁ ἀλλογενὴς οὗτος [ho allogenēs houtos], “this foreigner” or “this alien.”

Both Samaritans and the Jews of Judea and the Galilee were monotheists—a rarity back then—who revered the(ir own version of the) Torah and looked forward to a coming Messiah. Why the conflict? Well …

שׁוֹמְרוֹן [Showm’rown] (Which, Being

Translated, Is Σαμάρεια [Samareia])

Seven hundred years earlier, Samaria had been the heart of the Kingdom of Israel, the more prosperous northern twin of the Kingdom of Judah. The Israelite capital, also called Samaria, was built quite near the modern city of Nablus, adjacent to Mount Gerizim, the mountain on which Deuteronomy prescribed a monument should be set up listing the blessings promised for following the Torah. City and mountain alike were near Shiloh, where the Tabernacle was pitched before its relocation to Jerusalem.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire, which throve from the ninth to seventh centuries BC, conquered Israel bit by bit from 732 to 722 BC, and deported huge numbers of the populace. Resettlement was a common element in Assyrian imperial policy, the idea being to break the spirit of the populace, and thus discourage rebellion, by separating them from their ancestral homes. (This is the origin of the “Ten Lost Tribes”; the expression is a little misleading, but the Gileadite tribes of Reuben and Gad and the tribe of Dan effectively disappear from the Bible after the Assyrian conquest, while the only mention of Naphthali is in the book of Tobit, which some commentators adjudge a historical novel rather than a history.) Accordingly, the deportations probably focused on the aristocrats and scribes. We know that not all the populace were deported. During the reign of Hezekiah (727-697 BC?3) in Judah, he appealed to remnants of the tribes of Asher, Ephraim, Issachar, Manasseh, and Zebulun to come to Jerusalem for the Passover, and some of them responded—though even then, as II Chronicles 30 notes, the northerners had evidently not been properly prepared with due instruction in ritual purity. Judah even appears to have asserted control over some of central Canaan, as Assyria weakened over the following century.

But around the close of that century, the reckoning came for Judah too—this time at Babylonian rather than Assyrian hands. Solomon’s Temple was destroyed, and the Judahite political and cultural elites were likewise deported to the environs of Babylon. (They still called the place Babel, a name that means “gate of God,” but its radical,4 בבל [b-b-l], is punningly associated in Genesis with the radical בלל [b-l-l], meaning “mix, mingle; confuse”).

Khirbet Samara, site of a 4th-c. Samaritan

synagogue probably abandoned in the late 5th/

early 6th c. Photo by Bukvoed, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

It’s hard to know how much distinction there was between the Judean and Samarian commoners who remained in the Holy Land between the destruction of the First Temple and the founding of the Second—perhaps little; perhaps a great deal. Regardless, late in the sixth century, Judahites began to return there from Babylonia under the guidance of Zerubbabel, Ezra the Scribe, and Nehemiah, and the Second Temple was built between 535 and 516 BC, the date of its consecration.5 As the book of Ezra-Nehemiah relates, the Samarians asked to aid in the construction of the Temple, but the Judean leadership refused—the Biblical account describes them already as “enemies” and implies that their offers of help were insincere. Given the intense concern with ritual purity in this book, it’s possible that the Judeans believed Samarian involvement would ceremonially pollute the site.6 This, predictably enough (even if these offers were insincere in the first place), caused great resentment among the people of Samaria.

But this was not all. Now, it is only justice to note that the Samaritans themselves (of whom a few hundred exist to this day) dispute this interpretation of the site in question. However, archæological investigations on Mount Gerizim have uncovered a site that certainly seems to be a Samaritan temple. This corresponds to a passing allusion in II Maccabees;7 it also aligns with an account by Josephus—chronologically flawed in places, but thought to be correct in basic outline—speaking of this temple’s existence and, around 110 BC, its destruction by one of the Hasmonean kings.8 This too would, or so one imagines, leave some ill-feeling in its wake.

“Ye Worship Ye Know Not What”

Dome of the Church of St. Photini (the “woman

at the well”) outside Nablus. Photo by Wikimedia

contributor Tiamat, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0

license (source).

How does this come into Jesus’ ministry? Only three substantial interactions between him and Samaritans occur in the Gospels, two in Luke and one in John, all mentioned above. Conspicuously, in all three cases, he does or says something to indicate that it is mainstream Judaic and not Samaritan doctrine that is correct. In the first two stories, this is implicit: The Samaritans refuse him hospitality because he is determined to observe Passover in Jerusalem, not on Mount Gerizim; he sends the ten lepers to the high priest in Judea rather than to the Samaritan high priest. In the third, he says, in reply to the woman’s question about whether the Samaritan or Judaic view of the Temple is correct, that

the hour cometh, when ye shall neither in this mountain, nor yet at Jerusalem, worship the Father. Ye worship ye know not what: we know what we worship: for salvation is of the Jews. But the hour cometh, and now is, when the true worshippers shall worship the Father in spirit and in truth: for the Father seeketh such to worship him.

—John 4:21-24

The Temple is soon to be superseded, so on one level the question hardly matters. Yet at the same time, there is a right answer to the question, and Jesus—though not pushy (he waits for her to raise the issue), and apparently more willing to accept Samaritan sanitary and/or ritual standards than most Jews—is not shy about giving it. He is clearly on board with the general view of other Pharisees that Samaritanism is a schismatic and heretical branch of Judaism; indeed, given his allusion to “foreigners” and his exclusion of them from “the lost sheep of the house of Israel” in Matthew 10, he at least appears to endorse the severe view that Samaritans are not, in the strict sense, Jews at all (or at least not in a sense the Apostles are equipped to address without further instruction from him first).

So what’s going on with this parable, where the hero is a Samaritan? Translated into contemporary Catholic terms, this would be a bit like a story in which a bishop (pick one you admire) and a nun (from your favorite order) pass by on the other side of the road, only for a friendly lady-vicar with a colorful jumper to stop and help. What gives, O Lord?

My answer to that question is after the textual notes. This is partly for suspense; it’s also partly because I think it’s wise to reread the parable before getting the answer.

Luke 10:25-37, RSV-CE

And behold, a lawyer stood up to put him to the test, saying, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” He said to him, “What is written in the law? How do you read?” And he answered, “You shall lovea the Lord your Godb withc all your heart,d and withc all your soul,d and withc all your strength,d and withc all your mind;d and your neighbore as yourself.” And he said to him, “You have answered right; do this, and you will live.”

But he, desiring to justify himself, said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?” fJesus replied, “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and he fell among robbers, who stripped him and beat him, and departed, leaving him half dead. Now by chance a priest was going down that road; and when he saw him he passed by on the other side. So likewise a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he journeyed, came to where he was; and when he saw him, he had compassion, and went to him and bound up his wounds, pouring on oil and wine;g then he set him on his own beast and brought him to an inn,h and took care of him. And the next day he took out two denariii and gave them to the innkeeper, saying, ‘Take care of him; and whatever more you spend, I will repay you when I come back.’ Which of these three, do you think,j proved neighbor to the man who fell among the robbers?” He said, “The one who showedk mercy on him.” And Jesus said to him, “Go and dok likewise.”

Luke 10:25-37, my translation

Les Pharisiens et les Saducéens Viennent Pour

Tenter Jésus [The Pharisees and Sadducees

Come to Tempt Jesus] (1894), by James Tissot.

And look, an expert in the Law stood up to interrogate him, saying, “Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?”

He said to him, “What is written in the Law? How do you read it?”

He said in answer: “‘You shall lovea the Lord your Godb fromc your whole heartd and inc your whole sould and inc your whole strengthd and inc your whole mind,’d and ‘your neighbore as yourself.'”

He told him, “You have answered rightly; do this and you will live.”

Wanting to justify himself, he said to Jesus, “And who is ‘my neighbor’?”

Taking it up,f Jesus said: “A certain person was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho and was surrounded by muggers—they stripped him and inflicted wounds on him, and left, quitting him half-dead. By happenstance, a certain priest was going down that road, and, seeing him, he passed on the opposite side; likewise, a Levite came by the place too and, seeing him, passed on the opposite side. A certain Samaritan, traveling, came by the place, and, seeing him, he was heartwrenched; and he came up to him and poured oil and wineg on his injuries and bandaged them, and, having hoisted him onto his own animal, he led him into a hostelh and took care of him. And in the morning, he threw out two denariii and gave them to the hosteler, and said: ‘Take care of him—and if you spend any more than this, I will restore that to you on my return.’

“Which of these three seems to youj to have been a neighbor to the one surrounded by the muggers?”

He told him: “The one who actedk with pity toward him.”

Jesus told him, “Go and actk likewise.”

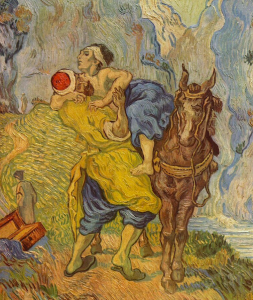

The Good Samaritan, After Delacroix (1890), by

Vincent van Gogh, who I had no idea had painted

any Biblical scenes!

Textual Notes

a. You shall love | Ἀγαπήσεις [Agapēseis]: Far from being a new or specifically Christian teaching (as I’ve occasionally seen it represented in Christian sources), this was already treated by most practicing Jews as the greatest commandment of the Torah. It forms part of the Judaic profession of faith, the Shema—which, according to Mark, Jesus quoted in full when he was challenged by a scribe to name the greatest commandment, and which was and is said twice daily by observant Jews.

b. the Lord your God | κύριον τὸν θεόν σου [kürion ton theon sou]: Κύριος [kürios], meaning “lord” or “master,” was a near equivalent in Greek of the Hebrew בַּעַל [baṛal] (usually transcribed baal), a word used both for local Canaanite deities and as a form of address from wives to husbands—hence the otherwise-cryptic promise in Hosea 2:16-17. It was more exactly equivalent to אֲדוֹנָי [‘adhownay], which lectors in synagogues and the Temple generally used in place of the Tetragrammaton (which was only pronounced in the Temple itself, and only on Yom Kippur); English-language Bibles’ use of “the LORD,” with small capitals instead of lower-case, to represent the Tetragrammaton reflects this practice. (I’m given to understand that אֲדוֹנָי is still used for this purpose in the synagogue today, but that other practices are also observed, including saying הַשֵּׁם [ha-Shêm], literally “the Name,” or simply pausing briefly in silence.)

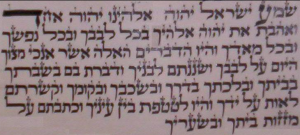

The Shema Yisroel (“Hear O Israel”) on a

tefillin scroll. Note the decorative crowns

placed on certain letters, and the exaggerated

ע and ד; the word עֵד [ṛêdh] means “witness.”

c. with … with … with … with/from … in … in … in | ἐξ … ἐν … ἐν … ἐν [ex … en … en … en]: The RSV’s decision to use “with” for all four prepositions here might be either or both of two things: an idiomatic choice (since in English you “believe things with all your heart” and the like), or their preference for a different reading of Luke. The Society of Biblical Literature is the Greek I normally use, and its text has ex-en-etc., but some manuscripts (e.g. the Textus Receptus) instead have ex-ex-ex-ex. My kneejerk reaction is that the SBL’s reading appears to fit the rule that it is more common for copyists to level differences than introduce new ones (especially when it’s a string of short prepositions that start with the same letter!).

d. heart … soul … strength … mind | καρδίας … ψυχῇ … ἰσχύϊ … διανοίᾳ [kardias … psüchē … ischüi … dianoia]: It’s common in many cultures to associate different parts of the body with different aspects of the personality: The heart, liver, stomach, and kidneys are favorites, and the brain, spleen, and gall bladder are not unknown (though the brain is a less universal feature9 of such lists than we might think—the ancient Egyptians famously liquefied and discarded the brain as part of the mummification process). In both Hebrew and Greek, the heart was held to be the core of the personality, at once its deepest and its most central part.

It’s important to note that in Classical Antiquity, the heart was considered the main organ of thinking and decision, not the organ of sentiment, as we usually consider it. The Latin word cordātus, derived from cor “heart,” is exemplary: A man who is cordātus is not, as we might expect, one who is compassionate or easily moved; rather, he is one who is sensible, shows sound judgment, “has a good head on his shoulders.” (There are many contexts in the New Testament and much other classical literature in which we would be well served to translate cor and καρδία as “mind” instead of “heart,” even though the organ associated with these terms is the red pumping thing.) Emotion would probably be assigned to the ψυχή [psüchē], most often translated “soul” or “life,” though it could possibly be attributed to the ἰσχύς [ischüs], if that word is to be taken as “physical strength” and thus, by metonymy, the body.

Finally, διάνοια also means “mind”—hence my choice in translating this text to stick to “heart” for καρδία after all—but “mind” in a slightly different sense. Where καρδία is the seat of judgment, choice, and action, διάνοια is more “intellect” in the pure or abstract sense; it is a compound built from νόος [noos] “mind” and the preposition διά “across, through,” making it an almost-literal equivalent of “the capacity to think through things.” I think the Hebraic equivalent would probably be the “understanding,” that favorite topic of the Book of Proverbs.

e. neighbor | πλησίον [plēsion]: This word, taken hyper-literally, means “nearby-one,” and in that sense is exceedingly well-translated with “neighbor,” which to this day shows a trace of the element “nigh.”

Hillel the Elder teaching, as depicted on the

bronze Knesset Menorah (1956) by Benno Elkan,

located in Jerusalem. Photograph by Tamar

ha-Yardeni, taken in 2008 (source).

Regarding the Second-Greatest Commandment more generally. There is a famous story about Hillel the Elder, a celebrated sage of the Pharisees, who was about seventy years old when Jesus was born (and who was incidentally the grandfather of Gamaliel I). He served as the Nasi of the Sanhedrin for many years; he was well-known for being generous, patient, and compassionate in his application of the Torah, in contrast to the stern, rigorous character of his Av Beyt Din, Shammai the Elder. A cleverly obnoxious Gentile approached Shammai and said he would convert to Judaism if Shammai could teach him the whole Torah while he, the Gentile, was standing on one foot. Unsurprisingly, Shammai was not the type to suffer fools, or worse, clever people, gladly; he chased the man off, a response for which there is a great deal to be said.

The wag then approached Hillel, who accepted the challenge. His interlocutor duly began standing on one foot, at which Hillel declaimed: “‘That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow.’ There, that is the Law; the rest is commentary on it. Go study already.” The goy in question had to admit defeat, and, according to the story, converted. This formula is sometimes called the Silver Rule,10 parallel of course to the positive recasting found in the Golden Rule—the Silver forbids the repugnant, where the Golden enjoins the desirable.

f. —/Taking it up | ὑπολαβὼν [hüpolabōn]: It isn’t all that strange that the RSV omits to translate this word. The verb from which this participle is derived, ὑπολαμβάνω [hüpolambanō], could to some extent function as a discursive, one of those “filler” words you include in a paragraph’s worth of speech (almost always narrative) not because it’s essential to the meaning, but just because it flows better that way. That may be all Luke meant by it here, but I think it’s being used more in the sense of Jesus taking up the challenge (or at least, problem) implied by the question, which he could of course have ignored—I mean, it’s not a question that screams “good faith” even on the surface.

g. oil and wine | ἔλαιον καὶ οἶνον [elaion kai oinon]: Thanks to the essential oils people, I couldn’t track down reliable information about what olive oil is likely to do to wounds (though I imagine it’d make bandages a little comfier, if nothing else). Wine, on the other hand, was invaluable as a disinfectant, since the alcohol it contains kills microbes.

Courtyard of the Funduq al-Najjarin,

a traditional inn in Morocco. Photo by

Joseph Renalias, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

h. inn/hostel | πανδοχεῖον [pandocheion]: To our minds, the word inn conjures an image of a house-like structure (but much larger), with a common room featuring a large hearth, and a dinner of bread and stew from the kitchen (perhaps a perpetual stew). This isn’t quite the idea of the hostel being referred to—not least because the inn, with its northwestern European associations, is sturdily built to keep out cold winds, snow, and rain.

A closer but unfamiliar equivalent to the πανδοχεῖον would have been “caravanserai.” These are travelers’ lodgings, usually quite cheap, that have existed for millennia in North Africa, the Near East, and Central Asia; rather than thick walls and a great hearth to keep the icy winter out, they have open, pillared courtyards and covered verandahs that catch cool breezes without stifling them, to siphon off the heat and sweat. They were generally built either in cities, or several miles apart from one another along major travel routes (the idea being that—unless you were in a tearing rush, which is not recommended in deserts—you could go from caravanserai to caravanserai, resting at one each night). Many, like the Moroccan inn pictured above, were splendidly built, even luxurious, while some were little more than pavilions that offered a place to cluster your belongings, a trough for the animals, and a meager supper—kind of a “hotel/motel” range of possibilities. They weren’t hospitals, to which there was no exact equivalent in the ancient world,11 and not all of them were equally secure (petty theft might be rampant at a particularly bad caravanserai, as it might be at a poorly-maintained hostel today), but even an average caravanserai would certainly be the best option in the circumstances of the parable.

i. two denarii | δύο δηνάρια [düo dēnaria]: This was two days’ wages for a laborer. Unfortunately, because of how differently prices relate to each other now than they did in the ancient world, the value of a denarius doesn’t map neatly onto modern money; you’ll get estimates of anything from $4 to $50 if you try to look it up directly. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to dig anything up about the typical price of a night’s stay at a πανδοχεῖον, so I can’t clearly estimate how long a stay the Samaritan has purchased exactly (though I can tell you that it was far less than a whole denarius per night).

Eight Roman dēnāriī, ranging from the second c.

BC to the third CE. Photo by Wikimedia contri-

butor M123, used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license

(source).

However, one thing that strikes me here is how trusting the Samaritan is being. Keepers of caravanserais did not have a great reputation in this day and age, any more than the owner of a Motel 6. The Samaritan isn’t being naïve; he has the good sense to (1) make it clear he’s coming back and (2) not say when, so he’ll notice if the guy who got mugged is un-cared for or has “mysteriously” disappeared. But, despite this whole errand being a result of a quite vivid and practical example of the lesson Sometimes strangers will hurt you, he still enlists someone he’s presumably never met in caring for this stranger, on the strength of mere need’s appeal to our common humanity.

j. do you think/seems to you | δοκεῖ [dokei]: The verb δοκέω [dokeō] basically means “to appear, seem.” It developed in two semantic directions. One was “to seem (but falsely); to deceive,” and in this sense δοκέω became the root of the term docetist, meaning those heretical sects that claimed Jesus’ apparent body was only a phantom. The other was “to seem (genuinely); to be obvious, be manifest.” It is from this that we get δόξα [doxa], originally meaning “opinion” (your personal “it seems to me”), which in turn bifurcated. Opinion can be fortified into belief: thus, orthodoxy. Alternatively, it can be extended along a different dimension, into a reputation, fame, and finally glory: thence, doxology.

k. showed … do/acted … act | ποιήσας … ποίει [poiēsas … poiei]: The verb ποιέω [poieō] in Greek most often means “to make”; however, it often occurs in places where English would use the word “do,” and has a number of other extended and related meanings accordingly (much like its Latin counterpart, faciō). In isolation, “took pity” would be a smoother translation of the first phrase, but “acted with pity” better exhibits the immediate, emphatic parallel of Jesus’ words here.

The Foreigner’s Faith

An allegorizing illumination of the parable

from the Rossano Gospels (6th c.), created in

Italy. Note the reddish-purple dye of the

parchment; it was also lettered in silver ink.

Judging from his words elsewhere, both to and about Samaritans in the concrete, Jesus isn’t saying that theology doesn’t matter. (He isn’t primarily discussing theology in the first place, after all.) However, speaking as one who, by temperament and upbringing, was very much primed to consider People will think theology doesn’t matter to be the great danger of this text: It isn’t.

The great danger of this text is the danger of hearing it and continuing to ignore the well-being of your neighbor. That, after all, is what prompted the Torah scholar here to try and wriggle out of the blunt, uncomplicated idea of “one’s neighbor” in favor of something more attractive. The choice of a Samaritan for the hero12 drives this point home, especially if everyone present, including Jesus, agreed that the Samaritans were objectively wrong about their theology (where it differed from Pharisaic theology, anyway). All of the focus for imitation in that case has to fall upon what the Samaritan does, not who he is or what he thinks.

And take note that Jesus never agrees to, and doesn’t, answer the question that this scribe actually asked. He reframes the problem completely and poses a new question of his own, one focused on what we ought to do and not on what we can get out of doing. We are proud, lazy creatures who don’t want to hear that; we would much rather righteousness were arranged to suit our convenience—we’re good at theology, perhaps, or we take sincere pleasure and pride in our distinguished ancestry. Which is fine. But if these are advanced as if they were any sort of reason we might be excused, just this once, from love of neighbor? the Bible’s only reply is, “Tough.”

It did say what it was on the tin.

Footnotes

1There is at least one other passing mention of Samaritans in John, namely in 8:48, but there it is merely a term of abuse.

2I tried to check this so I could offer more than a guess, but all I could find were page after page of advertisements for some hiking trail in Michigan (which apparently also has a “Jordan River”).

3Working out the precise chronology of Ancient Near Eastern history is notoriously difficult, and most accounts are controversial. The estimate I have given is based on that of Dr. Gershon Galil of the University of Haifa. Other approximations of Hezekiah’s reign place him a decade or so later, taking the throne in 716 or 715, and dying close to 687.

4In Semitic languages, a radical is a series of consonants (usually three, sometimes two) that carries some meaning or complex of meanings. Words are formed from radicals by inserting vowels in various patterns, attaching prefixes or suffixes, etc. For example, in Hebrew, the radical q-d-sh carries the meaning “holiness”: with one set of modifications, this becomes part of the term beyt ha-miqdash, literally “the holy house,” i.e. the Temple; with another, it becomes l’qadash, the infinitive verb “to hallow, consecrate”; with a third, it becomes qodesh, a non-specialized word for “holy.” Much of the wordplay in Hebrew comes from words that sound or look similar though belonging to different radicals, or derive from a single radical but have different vowel insertions.

5It’s from about this point that we can speak more usefully of Judea and Judeans than Judah and Judahites; the Persian province of Yehud Medinata, the Ptolemaic and Seleucid province of Ioudaia, the Hasmonean kingdom of Yehud, and the Roman province of Iudæa form a continuous political entity, albeit not usually an independent one.

6Ezra-Nehemiah is especially concerned with the Torah’s ritual purity code. The Torah is strict about certain groups being barred from entering the formal assembly of the people in worship: namely, certain ethnicities, eunuchs, and children born out of wedlock. No one with any known Ammonite or Moabite ancestry was allowed, and no one who was more than a quarter Edomite or Egyptian was either. The general opinion about Samaria among Jews was that Gentiles settled there by the Assyrians had blended with the local Samarian Jewish populace, making their admissibility to the Temple’s precincts unclear—and possibly introducing illegitimacy into their ancestry as well, if these foreigners’ marital customs did not satisfy Judaic requirements. If this was the Judean concern, nothing short of wholesale conversion to mainstream Judaism could have made the Samarians eligible even in principle to aid in building the Temple; and every prospective worker would then have had to have their lineage examined for illegitimacy (by Judaic, not Samarian, standards), any Ammonite or Moabite ancestry, and Edomite or Egyptian parentage—any of which, it appears, would be disqualifying even with conversion. Note that the foes of the Second Temple in Nehemiah are described as Sanballat the Horonite, Tobiah the Ammonite, and Geshem the Arabian, the ethnic designations most likely indicating their paternal ancestry; Horon may have been a village near Mount Gerizim, and the Ammonites were singled out for particular exclusion in the Torah, while the Arabians were Semitic Gentiles who habitually traded (and presumably intermarried) with Egypt. It is also easy to see why the Samarians didn’t take refusal on such grounds well.

7“… The king sent an Athenian senator to compel the Jews to forsake the laws of the their fathers …, and also to pollute the temple in Jerusalem and call it the temple of Olympian Zeus, and to call the one in Gerizim the temple of Zeus the Friend of Strangers, as did the people who dwelt in that place” (II Macc. 6:1-2, RSV-CE, emphasis mine). Note that the text here asserts that the Samaritans went along with the Hellenizing syncretism of the Seleucids; note, too, the distinction between the titles of the temple on Gerizim and the one on Zion—the former is associated with Zeus’ epithet Ξένιος [Xenios], denoting his special patronage of guests, foreigners, pilgrims, etc., while the latter is Zeus in his principal, implicitly noblest aspect.

8The Hasmonean dynasty were descended from the Maccabees. Despite being Levite by descent, they ruled as kings and queens from about 140 until the ascendancy of Herod the Great, who assumed the throne in 37 or 36.

9“Aristotle taught that the brain exists merely to cool the blood and is not involved in the process of thinking. This is true only of certain persons.” —Will Cuppy, The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody

10In more archaic English, when the adjectival ending -(e)n was more productive, this would have been called the Silvern Rule. I wish we’d kept this form, as I find “silvern” a disproportionately attractive word.

11There were a few partial equivalents to hospitals. The nearest—in the sense of being a place sick members of the public could resort to merely because they were sick—were Ἀσκληπιεῖα [Asklēpieia], temples to Asclepius, the demigod of healing (whose daughters included Ὑγιεία [Hügieia] and Πανάκεια [Panakeia], the roots of the terms hygiene and panacea): Standard procedure was for visitors to undergo a phase of purification for a few days (e.g., frequently bathing and eating a carefully regulated diet), and then spend a night sleeping in the temple itself, where Asclepius or one of his daughters would visit the patient in a dream; on rising, the Asclepion’s priest would interpret the dream and base his treatment upon it. Oh, did I mention that Asclepeia were full of dogs and snakes, which were animals sacred to Asclepius? Because they were full of dogs and snakes. (Of course not venomous snakes! That would be weird.) If for some reason you didn’t want to base your health care on a pagan priest’s interpretation of whatever dream you happened to have after spending the night in a shrine full of, and I can’t stress this enough, dogs and snakes, well, you’d better either a. be rich enough that your family built a private hospital or at least keeps a doctor on retainer, or b. be in the Roman army, since then you can go to to the camp’s valētūdinārium (infirmary). That term helpfully incorporates the verb valē, literally meaning “be strong” or “thrive,” but also used in Latin as a farewell (as in “valedictorian”)—which I’m sure soldiers never indulged in any extremely dark humor about. Hopefully they won’t need to use the bone lever! (If you’re wondering “What’s the bone lever?”, stop wondering that. What possible answer to that question could make you happier after knowing it than you were before?)

12Hero, not protagonist. The victim of the thieves is the protagonist.