When we were growing up, our parents often told us all kinds of stories about God. In them, we were given all kinds of images and descriptions for God which helped us imagine what was taking place. They were very simple, very anthropomorphic, because it was easier for us to think about God in such a fashion. For those raised in Christian homes, these images often came from and were adapted from Scripture. Holy men and women acted with God in a form which resembled a human person, perhaps like an elderly father-figure: the great old man looking down upon the earth from the sky. We could hardly understand or appreciate an invisible God; we needed something we could comprehend with our senses, and if we could not, it would be as if he did not truly exist.

When we were growing up, our parents often told us all kinds of stories about God. In them, we were given all kinds of images and descriptions for God which helped us imagine what was taking place. They were very simple, very anthropomorphic, because it was easier for us to think about God in such a fashion. For those raised in Christian homes, these images often came from and were adapted from Scripture. Holy men and women acted with God in a form which resembled a human person, perhaps like an elderly father-figure: the great old man looking down upon the earth from the sky. We could hardly understand or appreciate an invisible God; we needed something we could comprehend with our senses, and if we could not, it would be as if he did not truly exist.

Hopefully we have come to realize the divine creator is not a simple being or a thing like anything else around us. Anthropomorphic representations of God allow God to seem very personable, indeed, approachable, and this is certainly why such metaphors were used in Scripture and why parents used similar imagery in the stories they told. They help us to relate to and understand God in a very human fashion. The problem, of course, is that we end up misunderstanding these images and we begin to take them in an overly literal fashion, ignoring their metaphoric intent, creating for ourselves a very humanized notion of God.

Feuerbach was right in suggesting that the history of religion often has the problem that we deify humanity and its qualities, considering them to be what best represents God. What people tend to understand and look up to the most is themselves. They transpose what they think is great in themselves and predicate it to God, creating a representation of God which is based upon themselves and their ideals, which clearly will end up being false.

Scripture, when read simply, only reinforces this befuddlement. With the loss of poetic diction in society, simplistic, positivistic readings of Scripture become the norm; when an image of God is challenged as being false because it tries to comprehend God in a form which God does not hold, those defending that image invokes Scripture as their witness and so cast aside proper philosophical and theological responses.

Atheism is the natural reaction to the way God is portrayed by many believers and in this respect, the atheist is right in rejecting what they believe is represented by the concept of God. In many instances, they might be said to be truer to God by denying such false perceptions than so-called believers, for they know the falsehood of the idolatrous form being presented while the believer holding to such an image as absolute has made an infinitely inferior image of God for themselves to worship. Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook noted this as he suggested atheism often liberates humanity from such idolatry:

The tendency of unrefined people to see the divine essence as embodied in the words and in the letters alone is a source of embarrassment to humanity, and atheism arises as a painted outcry to liberate man from this narrow and alien pit, to raise him from the darkness of focusing on letters and expressions, to the light of thought and feelings, and finally to place his primary focus on the realm of morals. Atheism has a temporary legitimacy, for it is needed to purge away the aberrations that attached themselves to religious faith because of a deficiency in perception and in the divine service. [1]

God transcends us. While the divine nature reveals itself to us, what we encounter of it is less than what God is for himself. We know God through his activity, not his supra-transcendent nature, and so we know only about God but never the fullness of God himself. To try to limit the divine nature and confine it to human forms of comprehension and logic is to deny the truth of God. The supra-essential God is beyond all things, and so must be said to be in some way not a thing – that is, nothing, but the nothing from which all things flow. In a rather unique fashion, the denial of this by trying to make God a thing alongside any other thing, to be something which can be comprehended, is the only true atheism for it is the ultimate rejection of God. Anything else, any atheism which tries to deal with and object to limited conceptions of God are engaging something which is not God and so cannot be said to be truly denying God, though of course, it could be and often is the intent.

We describe and engage God in accordance to how God engages us and reveals himself to us, but all these revelations are a condescension of his, coming to us in categories and representations which we can understand but which must always be seen in an analogous fashion, realizing the distinction between who he is in himself and how we understand him is an insurmountable gulf. Paradoxically, it is a gulf which he can and does fill for us by that very revelation. Sergius Bulgakov, therefore, pointed out that as we must acknowledge the absolute transcendence of God in his nature, we must also recognize that he comes to us in an immanent form so that we do not end up with nothing for our faith to hold on to:

God in his transcendence is endlessly remove from the human being, goes away from him into a mystery beyond limit, by leaving in religious consciousness only NOT, only ABOVE, only emptiness. But religious self-consciousness cannot live, breathe, or be nourished by this emptiness alone – divine communion, divine experience, divine being constitute its vital foundation. Religion is possibly only inasmuch as the transcendent Divinity, the ineffable and unthinkable mystery, is revealed to humankind, and the Absolute for humankind (for, according to the expression of Newton, Deus est vocation aequivoca, God is a concept correlative to the one for whom he is God). To say it differently, the Absolute transcendent sets Itself as God, and consequently, accepts into Itself the distinction between God and the world, which includes the human being. God is both the Who and the What for humankind. [2]

The incomprehensible nature of God must be acknowledged by Christians and other theists alike. He transcends us. When we try to engage him, we grasp after him with conventions that might represent him in a fashion but we must always have a “but not that” for all such conventions, realizing that they are imperfect analogies to one who is so far beyond us we cannot truly establish who he is in himself with our words. The mystery of the truth, despite being beyond our comprehension, fascinates us and directs us towards itself in and with love. The further we journey with it, the more we find ourselves continuing to say “but not this, but not that,” and if we do not, then we will find our journey will come to an idolatrous end which ends up saying, “but not this,” to the truth of God. We must always be ready to be led deeper and deeper into the transcendence of God, up the magic mountain of transfiguration which has no end.

While recognizing the silence which transcends our words must be kept ever before us, we will want to speak about and proclaim with joy what we have encountered. When we do so, we will find ourselves coming to terms with the transcendence of the truth and the problems of human conventions. What we say will be of many different truths which we have come to know which nonetheless, following the conventions of human logic, will appear to be self-contradictory. While invaluable, logic is a human tool, a blunt instrument, as Kant in his examination of antinomies long ago demonstrated. To overcome the way we might feel about this, we must always keep in mind that the logic of God transcends the words and conventions we use; everything we say about God, comes in and through words which constrict God and try to define the absolute in conventional form. As long as we focus on the conventions and argue about them through simple logical constructs, we will find all kinds of apparent contradictions; when we understand the conventions are mere pointers to what lies beyond them, then the logical problems will reveal themselves to be paradoxes and not absolute. Thus, we can discuss God with various terms and understand what is being pointed out by them if we remember they are truly pointers and not the thing itself which is being established by the terms. In this way, we find the truth of apophaticism once again established: we are denying what is said by human speech, not allowing ourselves to be confined by it, and yet we must be careful. As Henri de Lubac explained, not all denials are to be seen in the same way:

In the end we deny everything which, starting for the creature, we have affirmed of God. Nothing escapes that law. There is no conceivable exception to it. But we do not deny everything at the same stage of the dialectic, nor for the same reasons, nor in the same way.[3]

Notions about God which are constructed through pure human speculation will be denied in a way which differs from what is based upon the self-revelation of God. Likewise, denial of some absolute falsehood is based upon transcendent truth, while denial of what is established by the imperfection of human conventions allows for realization of engagement with truth being presented in those conventions and so the two forms of denials must not be seen as the same. To say a rabbit with horns does not exist is one form of denial, but this is not the kind of negation which is being implied when we discuss God. Sadly, many equivocate the two; this certainly is the problem we find coming from some forms of atheism: they are right to deny what is erroneously said about God but then they end going the wrong direction with their denial, with an empty nihilism instead of the transcendent Nothing which generates all things. Following Henri de Lubac with his adaptation of an idea from Origen, can call God in his transcendent Nothingness the life-generating abyss:

One must not say: God is not good. He is incomprehensible; but one does better to say: God is Goodness itself, and it is that Goodness which I cannot understand. One should not say: God is not the Father, he is the Abyss; one should say, “God is the paternal Abyss.”[4]

God is Nothing, the Nothing which transcends all things. To deny him as being a thing of and in the world of conventions is not to deny him but to deny him as being like any thing, any limited being. His Nothingness is the emptiness which is full, able to generate and establish all things though that emptiness. Thus, he is the paternal Abyss—he transcends al things, for all things come out of him; his emptiness generates all forms so all forms represent and can be seen to be derivative from his emptiness. And yet, because they come from him, he can be found and seen in all of them if only we empty ourselves of our limited way of God. We must deny and yet affirm. We must deny all the falsehood which gets associated with God so that we can affirm God. And in this fashion, atheism is a necessary stage for us to truly engage the truth of God itself, for its truth is the realization of the emptiness of our concepts of God.

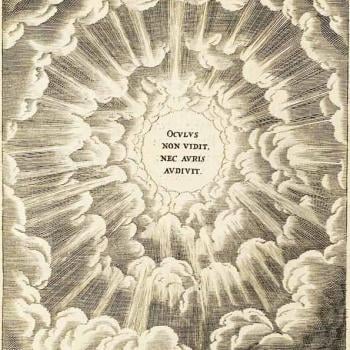

[IMG=Eye in the Sky”. Collage of iris and sky. By de:Benutzer:C.Löser [CC BY-SA 2.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Abraham Isaac Kook, “The Pangs of Cleansing” in Abraham Isaac Kook: The Lights of Penitence, Lights of Holiness, The Moral Principles, Essays, Letters and Poems. Trans. Ben Zion Bokser (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 265.

[2] Sergius Bulgakov, Unfading Light. Trans. Thomas Allan Smith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012), 109.

[3] Herni de Lubac, The Discovery of God. Trans. Alexander Dru (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1996), 124.

[4] Herni de Lubac, The Discovery of God, 136.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook