The Mystical Theology first explores our growing awareness of the truth of God. Dionysius understood that we must start with some of the crudest, most simplistic understanding of God through the way we engage him and his presence in and through the things which exist in creation. God exists, and we know God exists, because we see his presence reflected in all that exists. Everything, in the way they partake of existence, informs us of God, and so through all things, we can establish symbols by which the basic truth of God’s existence can be found. Then we are to explore those things and discern among them which better represents God because of their superior qualities, slowly transforming our awareness of God by recognizing the superiority of God to his creation. Both of these examinations of God through the things of the world before us represent the first, and most basic, way in which we encounter God through positive theological reflection that meditates and contemplates upon the qualities of God in the way the things of the world expresses to us various truths about God. Likewise, as revelation works in and through words which come out of the created order, we do not have to rely upon pure reason to see which names and qualities best represent the character of God for us: rather, God provides that foundation for us so we do not get led astray.

The Mystical Theology first explores our growing awareness of the truth of God. Dionysius understood that we must start with some of the crudest, most simplistic understanding of God through the way we engage him and his presence in and through the things which exist in creation. God exists, and we know God exists, because we see his presence reflected in all that exists. Everything, in the way they partake of existence, informs us of God, and so through all things, we can establish symbols by which the basic truth of God’s existence can be found. Then we are to explore those things and discern among them which better represents God because of their superior qualities, slowly transforming our awareness of God by recognizing the superiority of God to his creation. Both of these examinations of God through the things of the world before us represent the first, and most basic, way in which we encounter God through positive theological reflection that meditates and contemplates upon the qualities of God in the way the things of the world expresses to us various truths about God. Likewise, as revelation works in and through words which come out of the created order, we do not have to rely upon pure reason to see which names and qualities best represent the character of God for us: rather, God provides that foundation for us so we do not get led astray.

Most theological exploration comes out of this type of engagement with God, using the things of the world, human reason, and revelation in order to establish conventions which point to the truth of God. This kataphatic or positive theology is useful, but because it does not represent the fullness of truth which is found in God himself; what is stated must not be confused with the absolute truth of God as it exists in God himself. Christians speak about God, but there is always the caveat that God cannot be confined by any speech, even by the greatest and smartest theologians in their theological expositions. Christians know God exists, they encounter God’s work in creation which allows them to know something about him, they use revelation from Scripture and tradition to refine their discussions of God, but in the end, they must always realize the relative value of such kataphatic theology.

Revelation must always hold a central position in our theological reflection because God is greater than our human comprehension, and so the truths of God cannot be fully discerned by our reason. We can think and contemplate about God, but eventually, we will find ourselves at a wall, where the truth of God is outside of our ability to understand, and therefore, reason will find itself having to recede if we are to receive the truth. In order to meet us where we are at, God reveals himself to us; revelation is in itself a form of God’s self-emptying; he encounters us in a form which might be beyond our reason to establish but in which we are able to learn and come to an understanding, so that we can then be moved towards him and seek after God not in the lowness of the human intellect, but in a transcendental way.

The second stage of our engagement with God is purgative. This is true, both in the personal sense, where we overcome our selfish, egotistical habits which keep us confined in ourselves through sin, because the contamination of sin veils the truth of God from us, but also in a theological sense, where we start countering and objecting to all expressions used to discuss God, denying them so that we can slowly refine our vision and understanding of God. All theological expressions, even those found in revelation, are denied because even the best of them ends up confining God, establishing an inferior presentation of God than who and what he is in himself. This is the stage of apophatic or negative theology, where we overthrow the kataphatic expressions of God. For us to do so properly, however, we must also overthrow all the taint of sin in our lives; indeed, we should be finding the purification of our personal character will find itself linked to the purification of our minds; when we are free from the taint of sin and conventional thoughts, we will find ourselves free to truly experience God.

Apophatic theology turns us away from our reason, from our intellect, away from our attempts to define or express God. It is founded upon the simple principle: God is greater, always greater, than any theological definition for God will allow him to be. Everything we say about him in positive theology, the first stage of our encounter with God, must be radically denied with a firm no. It is not God. It is not what God is. God is nothing which can be stated. Anything which is used to describe God must be denied, because God is not it. God transcends us; God cannot be and will not be captured by us in our thoughts, in our description of him. To truly grasp this, however, requires self-purification, so that we stop attaching ourselves to the world, that is, stop being tied to the things of the word, for as long as we continued with an attached engagement with the world, we will not be able to receive the indeterminate truth of God. That is, sin creates habitual bonds that fetter us to the world, keeping us turned away from God. To become detached, we must break those fetters, and the best way to break them is to examine the things of the world and see how and why we have falsified them in our thoughts; once we do that, we will have learned the means by which we can engage apophaticism.

The problem with the second stage of our engagement with God is that it is capable of being misunderstood and turned to a thoroughgoing nihilism. Negation of the world, and through it, all that we say about God is valid, but we must also negate that negation itself, lest we end up nihilists. By denying kataphatic theology, we are affirming the transcendence of the truth, especially the truth of God, realizing it is beyond all human speech, thought and philosophical construct. But this is true also in relation to our negations of God. We must deny our denials, because our denials themselves come in the form of human conventions; without such a denial, it is easy to see why nothingness itself is seen as the absolute instead a convention used to express the transcendence of the absolute. Through our denial, including our denial of our denials, we truly empty ourselves, so that all we have is what lies beyond ourselves: the truth unveiled.

God is encountered; the more we open ourselves to him, the more we find ourselves in union with him, until at last we have a union of love which puts us entirely within God, seeing and experience all things in the transcendence of God so that we go beyond all affirmation and all negation but to the silence, to the true mystical state, where God is all in all and we encounter and unite ourselves to God to experience God in an unknowing beyond thought and speech, as St. Edith Stein explained:

And something will appear in both theologies that turn any knowledge of God into the experience of God: the personal encounter with him. When this at last becomes the person’s own living experience and is no longer mediated by images and parables nor even by ideas – nor by anything that may be given a name – then and only then do we have “secret revelation” in the most proper sense, “mystical theology.” God’s self-revelation in stillness. This is the summit whither the degrees of knowledge lead.[2]

Negation is always with words; we must find a way to silence ourselves, including our thoughts, in order to engage God as God and not as a thought construct or as something which is confined to our intellectual capability. We are to transcend ourselves and what we think we know if we want to enter the bright darkness of God, the radiant light which shines so bright, we become blinded by it. Then we will come to know and realize God, not in theory, nor in a restricted theological form, but in the true light of God which is beyond our comprehension. What we receive in that experience, of course, will be able to be explored by our intellect, and described by us in words; we will understand their relative value and so not be stuck by them, just as we will then be able to modify them as needed according to those who we meet and where they are in their understanding of the truth of God. That is, though we have been enlightened by the deifying grace of God in our union with God, we will still be who we are, able to reflect upon and engage the truths of God in human form, engaging kataphatic and apophatic theology so that we can help point others to the noble theological path which leads to the truth of God.

Positive theology is important because through it we grow to love God by knowing things about God, even if what we know comes to us in a derivative manner. By engaging it, we can be seen to be like those strike a piece of flint or who rub two pieces of wood together, hoping to produce a spark that leads to a flame. The love for God is the flame which we want to ignite; the spark, though it is not the flame, is the means by which the flame emerges:

So what do learning’s disputations and meditations contribute to this? Like blows [of a hammer on flint] that together produce sparks, struck for the sake of the first Good itself, these eventually kindle love for the Good in the rational soul. By this love it is immediately transported and united; and in the soul thus inflamed, straightway the divine light blazes down from on high.[3]

We can strike and strike and strike all we want and produce no flame if we are not aware of the nature of the wood or the flint, handling what we have been given improperly; the same, then, with our teaching: we must be aware of the understanding and awareness of our audience and adapt ourselves to them and their needs, slowly directing them from simple truths to higher truths, taking what they know and understand and using it to their own advantage. We must, therefore, use words, using such words to point out the limit and frailty of such words and yet use them to point to the truth which transcends words, understanding our words are able to establish analogies which represent the truth of God.

God, therefore, is mysterious; we can come to know God, but we must not confuse our understanding of God as being who and what God is in himself. With regards to the absolute truth of God, we must learn to silence ourselves and let God be found in that silence, encountered in that silence, a silence which is not just the elimination of words, but a silencing of the mind which would otherwise put up a veil between ourselves and God, keeping God distant from us. God is revealed to us when our senses, our mind, our intellect becomes entirely silenced; then we can experience God in pure love without restriction. This is what the mystical theology entails, the theology, the expression of God beyond words, in the silence of love. But it does so affirming and recognizing the value of our thoughts and ideas, of our imagination, knowing that so long as the apophatic “no” to our words exists beyond our words, we can express and portray the truth in beauty as a way to enkindle in us and others a great love and devotion to God.

Theology, therefore, is always adaptive; the greater the theologian, the greater their encounter with God, the better they can represent that encounter in and through their words because they realize the relativity of those words. Some theologians will have limited to no such encounter with God. This is not to say there is no value in what they have to offer. So long as they take the best of the theological tradition, accept what it has to say, and properly reflect upon it, they can help themselves and others along the path which leads to God. Theological reflection is useful for it does enkindle a love for God. The best theologians will be of sharp mind and have received some mystical experience with God. They will understand the theological tradition the best because it is not just theoretical, but experiential. They will be able to affirm the truth of positive theology without being imprisoned by its limitations. Since the truth of God is truth, no relativism is involved; this means not every expression about God is equally valid; but yet, contained in all error are the seeds of truth which can be picked up and used by those who truly have that experience of God, using it to lead more people to the fullness of the truth itself. This is possible because the transcendent God is also immanent with us and the rest of creation thanks to the incarnation. The invisible, incomprehensible God reveals himself to us while still preserving the integrity of his divinity, and therefore, affirming the ultimate truth through and in conventional truth while not being limited by the conventional truth. The two are one and yet distinct, never to be confused.

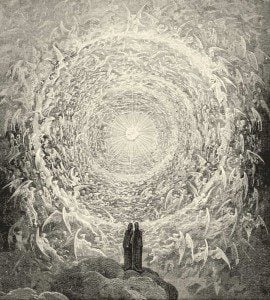

[Image= Dante and Beatrice gaze upon the highest Heaven by Gustave Doré [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Marsilio Ficino translated and wrote his commentary on The Mystical Theology before the Divine Names. Although the short nature of the work helped suggest itself as a good starting point for Ficino’s work with Dionysius, its content validated his decision, helping introduce to the renaissance his Platonically sensitive interpretation of a classic work.

[2] St. Edith Stein, “Ways to Know God” in Knowledge and Faith. Trans. Walter Redmond (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 2000), 116.

[3] Marsilio Ficino, Mystical Theology in Marsilio Ficino: On Dionysius the Areopagite. Volume I: Mystical Theology and The Divine Names, Part I. trans. And ed. Michael J. B. Allen (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 17.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook