A proper Christian spirituality has us embrace the need to be of service to others. Such service must be freely rendered: that is, it must not be something enforced, but rather, it should be done out of love. This is not to say we should ignore justice, saying that the enforcement of justice should be purely voluntary; grave injustices require action so that those who suffer them can find relief. Our loving service to others must, therefore, not be set in opposition to our obligations for justice, but rather, must be seen as something which complements and transcends such justice.

There are many ways which we can work for the benefit of others. Each of us is unique, and so each of us has our own unique gifts and talents; what is important is for us to discern how we can best put our talents to use. That is, we should not reduce Christian spirituality, and with it, loving service to others, into specific molds which we must conform to. We must engage others through our own personal qualities, what makes us unique, making sure we give a gift of ourselves to others in our service.

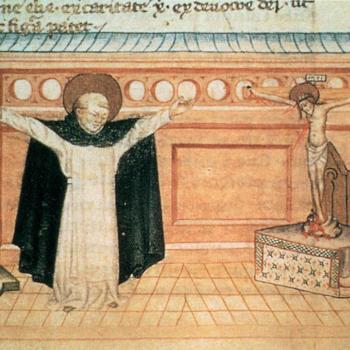

Christianity is personalistic, not individualistic, which is why our spirituality must take others into considerations. Our spiritual development requires us to move beyond individualistic piety, seeking to become holy all by ourselves, independent from everyone else. We must help each other in accordance to our ability to do so, in accord with our own personal charism. We certainly must not retreat from the world, ignoring our responsibility for others. No authentic Christian spirituality, even one which does include some element of retreat from the world, creates an absolute divide between the spiritual aspirant and everyone else. Monastic spirituality has always embraced this truth, which is why monks, even hermits, can be shown to move beyond their retreat and help those in need, or, if they are unable to do so, at least see their life of prayer as a life of priestly mediation, not just for themselves, but for the world. Similarly, those who are called to a more intellectual engagement of their faith must learn, through their studies, that they must act: they should not be pursuing knowledge for their own personal glory, or out of vain curiosity, but out of a love of truth, a love which will motivate them to act on what they learn.

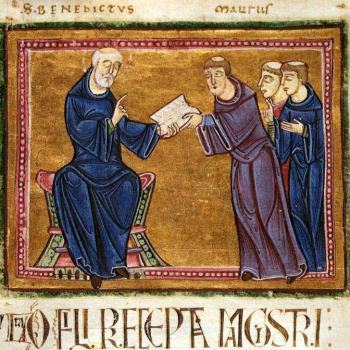

If we pursue knowledge for the sake of knowledge, for the sake of knowing more than others, without putting what we learn to good use, then, as St. Paul would say, we have gained nothing. This was understood and accepted by the greatest theologians of the church, such as its saintly Doctors; they did not pursue useless knowledge, indeed, they warned others against doing so: they asked and answered questions which they felt had value, not just for themselves, but for everyone. Knowledge can and should help us understand how we should act in the world, how to deal with the problems which lie before us, which is why its pursuit does not have to be in vain. We can see this in monastic spirituality, where, it is clear, monastic communities embraced the value of knowledge, seeking to preserve what it learned for the sake of the common good, so that such knowledge is not lost. This is exactly what we saw happening with the Benedictine tradition, a tradition which certainly remembered the need not only to pursue knowledge and to preserve it, but to act on it, as Joan Chittister explains:

The spiritual life is about more than piety or regular adherence to religious practices. To be truly spiritual we must, as Benedict of Nursia counsels in his ancient monastic Rule, give ourselves over to the ‘school of the Lord’s service.’ We need to bring knowledge to virtue so that our spiritually does not become a bad theology. A commitment to knowledge is what provides us with the tools we need to make judgments that are true and kind, compassionate and just. The knowledge of God makes us free of the kind of guilt and scrupulosity, compulsion and righteousness that tempt us to put more effort into maintaining institutions than plumbing God’s mysteries in our own lives.[1]

We are all called, each in our own way, to embrace the “school of the Lord’s service.” And while good monastic spirituality embraces this, with monks and nuns throughout history, doing what they can to help people in need, we can find many who become a monk or a nun with a desire to completely cut themselves off from the world, to ignore their responsibility to others, an in doing so, undermine the value of their retreat. Even those who were called to be hermits were told they should not do so out of hatred towards their fellow humanity, and that they should find a way to engage the common good in their solitude. St. Antony the Great, despite his love for solitude, knew he had to direct and guide those who followed him into the desert, but also, it is said, in and through his prayers and service to the community, he helped serve as a mediator for the world, sharing the grace which he had received the world at large. Similarly, when he heard that Christians were being imprisoned and martyred, he wanted to be with them, to suffer with them; while he was not taken in by the authorities, he helped minister to those who were in prison, giving them as much comfort and aid as he could. Likewise, when he heard about the conflict going on in Alexandria concerning the teachings of Arius, he made his way to the city to denounce Arianism.

We, therefore, must always understand we should not pursue our own spiritual advancement for the sake of vainglory; we should not seek after grace in order to jealously guard what we receive, trying to hold onto it as if it is ours alone; rather, we must follow after Jesus, embracing others with love, helping those who are in need:

By our involving service, especially to comfort the poor and set free the oppressed, we help in union with the risen Lord, who has received all power from His Father, to re-create this world and bring it into completion according to the plan of God is conceiving out of innumerable possibilities. God waits for our cooperative consent to work synergistically with Him.[2]

There are many ways this can be done. Those who have great amounts of money, food, shelter, clothing, or other similar material resources, should share them, especially with the poor and needy. Those who have political clout should use it to promote the common good, working to create a more just society, one which does not neglect those in dire need. Those who are more intellectually inclined must use their knowledge and wisdom to help teach and develop society so that society will not only know why the common good is important, it will have notions how best to promote it. Marsilio Ficino, therefore, was fulfilling this role, as an academic intellectual, when he exhorted his audience to follow the way of love: : “Therefore, most humane man, persevere in the service of humanity. Nothing is dearer to God than love. There is no surer sign of madness or of future misery than cruelty.” [3]

We must constantly examine ourselves, making sure we are doing what we can, not only for our own individual growth, but for the common good. Are we using our unique gifts only for our own sake, for our own pleasure and glory? It is imperative that we discern the gifts which we have been given and find the best way to use them, not just for ourselves, but for everyone. We certainly must not become so attached to those gifts that we end up thinking ourselves to be superior to others, for then, because of our pride, we risk end up thinking others do not deserve what we have to offer, finding ways to exclude them from the gifts which we are meant to share with them. If we think and act in such a way, we would be following Satan in his pride, and we will find, however great we think we might have become, that our pride will always take us down (as it is said to have taken Satan down).

[1] Joan Chittister, OSB, Life Ablaze: A Woman’s Novena (Franklin, WI: Sheed & Ward, 2000), 20-21.

[2] George Maloney, SJ, God’s Exploding Love (New York: Alba House. 1987), 14.

[3] Marsilio Ficino, The Letters of Marsilio Ficino. Volume 1. trans. by members of the Language Department of the School of Economic Science, London (London: Shepheard-Walwyn, 1975; repr. 1988), 101 [Letter 55 to Tommaso Minerbetti].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.