Society requires people to work together to promote the common good. It should be obvious that we must rely upon each other, that we can’t do everything all by ourselves. We all have skills and expertise which we can and should use to contribute to the common good, even as we must rely upon the skills others have, some of which we might never be able to attain if we tried. There will be people who have expertise in areas which we do not, and we will have to rely upon them and what they have to say, especially if their expertise deals with matters which we have little to no means which allow us to judge them and their advice. Of course, if they have proven themselves unreliable in areas which we can judge, if they show utter contempt for the common good, we have the means to question them and to look for the advice from others. Otherwise, it is best for us to give some modicum of trust to experts in the fields of their expertise. We can see this, for example, with healthcare, and what medical experts say we should do during a pandemic. They will sometimes have to direct society, telling people what to do, and people should do it – they should obey the experts, even if the experts tell them to do things they would rather not do, when it is for the sake of the common good and there is no moral justification to reject their advice (such as when experts say there is the need for a temporary lockdown during a pandemic). On the other hand, such experts, and society in general, will need to balance this out, making sure that people are given their own agency, recognizing that they have an ability to learn and decide many things for themselves. That is, while there is the need for laws and regulations to be put in place and enforced, requiring, therefore, the obedience of the community involved, there must be some flexibility, some freedom, given to the people as well. We must accept that people can and will make mistakes they will make bad decisions, and they should be free to do so as long as the consequences are not grave for society, or what they do tends to do extraordinary harm to those who are vulnerable and need our protection. With such freedom, various norms can be challenged, and through such challenges, reformed, making things for the better; if there is no flexibility, if everything is strictly regulated and absolute obedience is expected, there will be no ability to make things better. There is, therefore, a need to make sure society does not follow after two extremes, either an authoritarian, rigid system which demands absolute obedience, nor a system without structure, rules, or laws, because in both situations, the common good is overridden.

What is true for society is also true for religion. In any given religion, people are not free to make whatever doctrines or dogmas they would like to make. To be a member of a particular religion requires adherence to its teachings, at least on some level (as, of course, there can be within the religion itself, a debate about how much adherence is necessary, and how much flexibility or interpretation is allowed). The best religions, the most successful ones, can be shown to recognize and promote, at least to some degree, the value of human dignity, and with it, some level of personal liberty. Religious specialists, whether they are scholars, theologians, priests, or some sort of monk or nun, have roles to play, but so do the non-specialists. There needs to be flexibility, but there also needs to be some sort of structure with expectations given to the people. Historically, we have seen times in which those who are in positions of religious power and authority use too much of that power to enforce their whims, and in such a way, ended up undermining the liberty which their religion needed to thrive; at other times, religions end up facing an existential crisis as its followers begin to question the doctrines, dogmas, and moral expectations that has been handed down to them. Obedience can be and sometimes should be employed in religion in order to make sure its most basic, fundamental principles, are preserved; but, on the other hand, how a religion does this is important. Again, the faithful should be given as much freedom as possible, the freedom to explore, to question, to reform, to develop, for without such freedom, legality will undermine the life of the religion and the religion will wither and die.

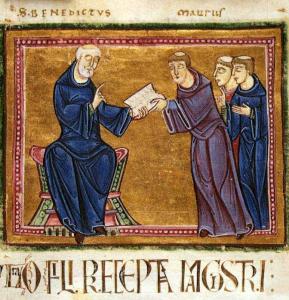

In various monastic traditions, the value of obedience is often highlighted, taught to all within a given community or monastery an important virtue which all those in the tradition must embrace. Those who were novices, those new to the community, especially are taught to consider obedience a virtue, as their community, and their spiritual director, will tell them things which they should do in order in order to properly fulfill their religious calling within that community. Monks often considered themselves to be spiritual athletes, and so it would be proper to compare the way they are mentored with the way a sports team is lead and directed by a coach. A team which will not listen to and follow its coach will not be too successful, and a community which does not know how to give proper adherence to the rules and expectations of the community, and the authorities in that community, will find that the purpose of that community will be thwarted. The point of obedience in a monastic community was not obedience itself, but rather, to make sure a person able to be helped and gain the experience they need (and hopefully, mature enough they will need little to no direction in the future).

Obedience, therefore, can and does have a role in society and in religion; but it can be and is often abused. Then, the potential good found in obedience turns into an evil, as the person who holds a position of power and authority ends up demanding absolute obedience, even on matters which are not good for the people involved, but for themselves. They often end up abusive to force people to do what they want, sometimes physically, sometimes mentally, but in all such situations they justify themselves by saying they are the one who has an authority which must not be questioned, that those who do question it, deserve what they have coming to them. In religion, those who abuse their authority, those who demand strict, absolute obedience without question, especially harm those who have low self-esteem, those who have not been given the tools they need to defend their own dignity and to grow in strength and agency as they should. Laura Swann, in her commentary on St. Benedict’s Rule, makes a good observation of the dangers behind obedience, especially in a religious setting. Often, people like the notion of holy obedience and give in to authoritarians because it serves as a crutch, making sure they do not have to make choices for themselves, choices they do not want to make because they have low self-esteem:

Immature obedience can be manipulative, passive-aggressive, complaining, and listless. It is motivated by fear of tyranny or low self-esteem. Obedience grounded in internalized self-hatred drains the family and community of energy and moves the focus away from the heart of the community. This false obedience dwells in a mentality of scarcity rather than the abundance of God.[1]

When dealing with obedience, therefore, it is important that those who are in positions of authority, either in society, or in religion, employ their authority for the good of all, making sure that their use of their authority does not undermine but rather promote human dignity and the common good. As there are bad actors in the world, those who are selfish and cruel, there will be times when authority must be used to protect the common good from them, but, on the other hand, we must make sure those who have authority are not the ones who are such bad actors. Indeed, just as an unjust law is no law and should not be obeyed, so immoral or abusive demands by authorities can be deemed to have no proper authority behind them. This is why, in a society ruled by a tyrant, society often has a duty to disobey the unjust demands of the tyrant; a facile notion of authority and obedience would say otherwise, which is what the tyrant hopes for, and why they focus on their authority, constantly explaining why they have it and must be obeyed.

[1] Laura Swan, Engaging Benedict: What the Rule Can Teach Us Today (Notre Dame, IN: Christian Classics, 2005), 54.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.