God, in his love for humanity, desires all of us to be saved (cf. 1 Tim. 2:4; Titus 2:11; 2Ptr. 3:9). The incarnation reveals the depths of God’s love. When we were still sinners turning our backs on God, we caused our own pain and sorrow as we disconnected ourselves from the source of every good, God. Nonetheless, God desired to help us, to give us every opportunity to open ourselves back up to him and receive his deifying grace. He became one of us, revealing the fullness of his love as he emptied himself out to us, letting us do to him all that we would want to do with our sin. In this way, God showed us the infinite depths of his love while he also revealed to us the limits of sin, where it can and will come to an end.

God, in his love for humanity, desires all of us to be saved (cf. 1 Tim. 2:4; Titus 2:11; 2Ptr. 3:9). The incarnation reveals the depths of God’s love. When we were still sinners turning our backs on God, we caused our own pain and sorrow as we disconnected ourselves from the source of every good, God. Nonetheless, God desired to help us, to give us every opportunity to open ourselves back up to him and receive his deifying grace. He became one of us, revealing the fullness of his love as he emptied himself out to us, letting us do to him all that we would want to do with our sin. In this way, God showed us the infinite depths of his love while he also revealed to us the limits of sin, where it can and will come to an end.

God emptied himself so that we can be free; he would not renounce our freedom for the sake of his desire, but he would work with us and engage us in our freedom, helping us reform and come back into union with him. He opens himself up to him so that we can open up to him, and in that mutual-openness, we find we take on and partake of his own freedom, so in that grace, we find our freedom becomes greater than ever before.

We can choose sin, but once we sin, it begins to corrupt us, limit us, imprison us into our own private little hell; God comes to us, offers us the aid we need to overcome that self-made hell so that we can once again be free as we unite ourselves to him and participate in his own incomprehensible freedom. Yet, despite all the power and destruction which came out of sin, although it impedes our efforts, although it limits us, it does not entirely destroy our innate goodness. Thanks to that goodness which remains, we still have some level of freedom, though the more we use what little we have to embrace sin, the more we limit ourselves, destroying and removing our personal subjectivity until, at last, if we let it get so far, we become entirely objective entities without personal freedom. Whether or not this will ever happen to us, or to anyone, is a major debate; Hans Urs von Balthasar thought it possible, but hoped it would not happen, and suggested that this should be the default Christian position.

But, as many upon hearing this ask, does not Scripture suggest there will be some, if not many, who will be damned? The Apocalypse, for example, states about eternity: “and if any one’s name was not found written in the book of life, he was thrown into the lake of fire” (Rev. 20:15 RSV). In his preaching of the last judgment, Jesus said, “When the Son of man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on his glorious throne. Before him will be gathered all the nations, and he will separate them one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will place the sheep at his right hand, but the goats at the left” (Matt. 25:31-33 RSV). Many other texts can be, and are used to declare some will suffer eternal perdition. It seems obvious, then, to state, Jesus would be a liar, and Scripture would be shown false, if this did not happen.

However, such texts are being misread because the nature of the prophecy is misunderstood. They are not, as Scrooge would say, the shadows of things which will be, but only shadows of what may be. Freedom is not eliminated by Jesus in his warnings about the future, rather, his warnings are set up to prevent that end. He came to save, not to judge; he did all that he could to save; he desires that none shall perish, and that means, he came to make it possible for all to partake of eternal life. Prophetic declarations of judgment in Scripture always serve as warnings; that is the point. There would be no reason to preach if there was no chance for reform and halting the destruction. Jesus said the sign he came to give the world was the sign of Jonah (cf. Matt. 12:38-41). Jonah had indicated that Nineveh would be destroyed. He did not entirely understand why he was called to say that to Nineveh, indeed, he thought it possible his warnings would come to naught. He misunderstood prophecy and what it would take for him to be seen as a false prophet. Jesus did not. Jesus knew that predictions of judgment are to serve as warnings, of shadows of what might be; as such, they are one of many tools which he uses to help set us up for our salvation.

St. John Chrysostom understood this point:

My Master, your promises are as good as is your Kingdom, which is expected, because it urges on; the Gehenna with which you threaten is evil because it frightens. In other words, the Kingdom incites toward the good, and hell frightens usefully. For God threatens with hell, not to throw into hell, but rather to deliver from hell. If He wanted to punish, he would not have threatened beforehand in order for us to escape the things he threatens. He threatens with the punishment so we will escape the experiencing of punishment. He frights with words so He will not punish with deeds.[1]

It is why we turn to the story of Jonah; not only did Jesus point to it as the sign which represents his own life and mission, but it also served as the prime example of how God works in and through prophecy to help reform people. Nineveh, Jonah preach, was to be destroyed in three days. The people listened to him and repented, changing their ways, overriding the cause of their own destruction. While some might think this meant his prophecy was a failure, it was actually successful, because the actual desire God had for it was fulfilled. Chrysostom pointed out that Jonah knew God’s desire to save the people, and that if he preached, God’s benevolence would prevail and Jonah could be declared a false prophet, forfeiting his life. This, Chrysostom thought, is why Jonah fled; he sensed what he was told to preach would not come to pass. Yet, because of God’s plan, Jonah could not flee from his duty; he would eventually find himself at Nineveh:

However, when the ocean returned him to dry land, and he arrived at Nineveh, he preached, saying, ‘Three days more and Nineveh shall be destroyed.’ Jonah himself reveals this, so you may learn that he fled away, having this thought in mind, that God is a lover of mankind and He repents of the wickedness He spoke about them, and, in this manner, Jonah was considered a false prophet. After he preached in the midst of Nineveh, he went out of the city in order to observe if anything should happen. When he saw three days had passed and nothing had happened anywhere near what was threatened, he then put forward his first thought and said, ‘Are these not my words that I was saying, that God is merciful and long-suffering and repents for men’s evils?’ [2]

The sign of Jonah is the sign of the preacher who not only warned of death and destruction, but also the sign of change, the sign of salvation. Jesus offered himself as the sign of Jonah fulfilled. He preached doom. He offered salvation. He reconfigured the world from within so that the corruption which had found its place within could be removed and the union between heaven and earth could once again be experienced.

For some, the threats of God are needed to get them to reconsider themselves and repent. This is not that fear of hellfire is the best motivation to follow God (love for God is), but for many, this is the foundation by which they come to know the good before they are able to transcend the threats and follow God out of pure love. Once love for God is pure, then following God will not be out of out of fear of hell, nor even out of desire for heaven, but for God himself, doing good for the sake of the good alone. Good will be seen as its own reward and loved for its own sake. But as so many of us are so caught up in ourselves, we need prompting from God to be rightfully set upon the path to God. We need help to overcome ourselves, that is our selfish egotism, and the warnings of God serve as that foundation. Once we truly have found ourselves on the way, once we have truly cut ourselves off from all that leads us astray, we will no longer be mere hired hands, but friends of God who follow his example and share his love with all.

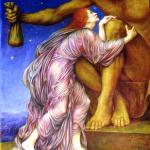

[Image= Jonah from Kennicott Bible S[Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] St. John Chrysostom, On Repentance and Almsgiving. Trans. Gus George Christu (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1998), 109.

[2] Ibid., 109 (See also pgs. 62-5 for more of his analysis on what is to be learned from the story of Jonah and Nineveh).

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook