God is one, simple, transcendent, divine principle. We talk about God with many names, but all of them, even the name of God, indicates a concept which is less than what God is in himself. He is called “God of gods” (cf. Deut. 10:17) because the notion of Godhood is something which can be shared with and participated in all who unite themselves with him. He is the source and foundation of the divine energies which deifies creation. With such a plurality, the problem we find emerging is how we are to understand the relationship of God as one simple divine principle with the plurality which emerges from him which allows us to know him and represent him with a plurality of names. This problem is just another version of the paradox from which we began our exploration: how can we talk about God an incomprehensible God? We talk about him in and through his attributes or names which come out of his economic activity, an activity which can be seen to be without limit and so allowing for an infinite variety of names which can be predicated to God. The incomprehensible nature of God relates to the oneness of God, while the knowledge which we have of God represents the infinite variety and ways God reveals himself to us.

God is one, simple, transcendent, divine principle. We talk about God with many names, but all of them, even the name of God, indicates a concept which is less than what God is in himself. He is called “God of gods” (cf. Deut. 10:17) because the notion of Godhood is something which can be shared with and participated in all who unite themselves with him. He is the source and foundation of the divine energies which deifies creation. With such a plurality, the problem we find emerging is how we are to understand the relationship of God as one simple divine principle with the plurality which emerges from him which allows us to know him and represent him with a plurality of names. This problem is just another version of the paradox from which we began our exploration: how can we talk about God an incomprehensible God? We talk about him in and through his attributes or names which come out of his economic activity, an activity which can be seen to be without limit and so allowing for an infinite variety of names which can be predicated to God. The incomprehensible nature of God relates to the oneness of God, while the knowledge which we have of God represents the infinite variety and ways God reveals himself to us.

For Proclus, the problem is given a simple answer: the plurality is accepted as a plurality of gods which are differentiated from the transcendent One. He has no problem accepting a plurality of gods, while accepting the over-arching transcendent One which lies beyond them and beyond all being, making God truly imparticipable:

For in the first place it is clear that the One is imparticipable: were it participated, it would thereby become the unity of a particular and cease to be the cause both of existent things and of the principles prior to existence.[1]

It is the gods, the plurality which comes out of the One, which we experience and come to know, and why, for the Platonist, the gods are an important part of their cosmology even if there is the higher One which lies beyond them:

For in producing themselves the gods produced the existents, and without the gods nothing could come into being and attain to measure and order; since it is by the gods’ power that all things reach completeness, and it is from the gods that they receive order and measure. Thus even the last kinds in the realm of existence are consequent upon gods who regulate even these, who bestow even on these life and formative power and completeness of being, who convert even these upon their good; and so also in the intermediate and the primal kinds. All things are bound up in the god and deeply rooted in them;, and through this cause they are preserved in being; if anything fall away from the gods and become utterly isolated from them, it retreats into non-being and is obliterated, since it is wholly bereft of the principles which maintained its unity.[2]

For the monotheists of the Abrahamic tradition, the distinction between the one and the many is understood and accepted on a logical basis, at least in relation to the way God works and interacts with his creation. God’s infinite transcendence, the Eyn-Sof of the Kabbalah, the Essence and Reality of Al’Arabi, and the divine essence of Palamas, is the transcendent One of Proclus. Unlike Proclus, the monotheists posit that the One in its transcendence can manifest itself in and through plurality. They suggest, each in their own way, that the One must not be limited, and if the One could not manifest itself in and through plurality, it would be limited, contradicting what it means for the One to be transcendent.

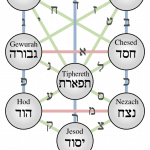

The plurality which comes out of the One, manifesting the One to contingent, limited beings (whether or not they are also infinite beings, as it is possible for something to be infinite and limited as mathematical equations can demonstrate) reveals the One transcending its transcendence in a kind of self-emptying which allows it truly to be transcendent and the One which is beyond our comprehension. God reveals himself in the Sefirot, or through the veils which he establishes to indicate his qualities, or through the divine energies, giving structure to our knowledge of him. That structure, then, forms the basis by which it is possible for us to say we comprehend something about God. What we comprehend is not God in himself, but God as he reveals himself to us. It is a revelation which is truly of God, and so is truly God, but it is God as established in positive theology. By giving us something which we can comprehend, moreover, we then are given a way by which we can be united with God. His self-revelation is the means by which we are deified, lifted up beyond ourselves as we find ourselves partakers of the divine reality.

There can be nothing outside of God. This means that all things are created by God. As they are created by him, they come out of his divine activity: God is revealed in and through all created realities. God is revealed in and through us as like in a mirror, with the quality of the mirror representing the quality of that image which is produced by us. The greater our being, the more we have opened ourselves to partake of God, the greater the reflection of God, and therefore, the greater representation of God which emerges. In a way, this is what we were made for: so that God can establish his reflection in us and so find himself seen as an other through us:

The Reality wanted to see the essences of His Most Beautiful Names or, to put it another way, to see His own Essence, in an all-inclusive object encompassing the whole [divine] Command, which qualified by existence, would reveal to Him His own mystery. [3]

Our spiritual relationship with God includes contemplation of God in and through the various ways he reveals himself. God transcends all which we can say of him, so we negate what we say, allowing the absolute to absolutely transcend all names which is given unto it; but that transcendence would be false if it is limited to mere abstraction which negates all things. We negate in order to engage and unite ourselves with what is revealed by God so that we can be defied in that revelation and become partakes of the divine:

Contemplation, then, is not simply abstraction and negation; it is a union and divinization which occurs mystically and ineffably by the grace of God, after the stripping away of everything from here below which imprints itself on the mind, or rather after the cessation of all intellectual activity; it is something which goes beyond abstraction (which is only the outward mark of the cessation).[4]

It is the grace of God, which is God, that allows us to be divinized; the more we experience of that self-revealing grace of God, the more we are deified, the more we can represent God by speaking about him through names and attributes which we know properly represent and express the divine in a conventional fashion. When we speak of God, when we express what we have received in our experience of God, we know through such experience we have only found ourselves at the tip of the iceberg and that there is a great unknown Reality which lies beyond what we know and experience. This unknown is the glorious mystery of the Eyn-Sof, the mystery of the great abyss which has no end, meaning there is going to be no end of revelation from God in our experience with him. He reveals himself showing himself to be like an onion, where every layer of self-revelation is as if he removes a veil only to show an unlimited number of veils which lie beyond:

For this reason the Ruler [God] is veiled, since the Reality has described Himself as being hidden in veils of darkness, which are the natural forms, and by veils of light, which are the subtle spirits.[5]

Every veil which encounter, we can uncover to reveal another, deeper, more mysterious veil. It is the light of grace which manifests itself in a form which we can experience; the light is the veil, and beyond it is a greater light which is so bright it would blind us if we see it, so that the Reality is hidden in veils of darkness, that is, ever greater, brighter lights of grace which we cannot see or comprehend until the grace we have has prepared us for further, more subtle depths of God’s glory. God reveals himself to us in the divine light of his grace, for he is the one who truly can take off the veil. If we try to get ahead of ourselves and uncover that veil for ourselves when we are not ready, we will suffer and burn in the experience of that transcendence, as the bright darkness will overwhelm us, which is far from what God wants for us as his beloved. This, then demonstrates how and why the names themselves, qualities which can be seen represented in the veils, are not all of the same kind: some are greater than others, some which we can know and understand now, and others which we will come to know if and when we are lifted up and ready for them. Not all names, not all qualities are equal to each other, and yet, in a mysterious way, as they all manifest God, they are one and the same, because there is but one God manifested in and through all things, making him truly all in all. It is this fashion which we can begin to see the relationship between God’s transcendence, simple and one, with his economic activity, which is infinite, because the foundation and base of all such activity is that some transcendence which in its transcendence can manifest itself not only in transcendence but in self-emptying revelation.

[IMG=Divine Finger Contact With God [CC0 Creative Commons] via pixabay]

[1] Proclus, The Elements of Theology. Trans. E.R. Dodds (Oxford: Clarendon Press,1963),103. [Prop 116]

[2] Proclus, The Elements of Theology, 127. [Prop. 144]

[3] Ibn Al’Arabi, The Bezels of Wisdom. Trans R.W.J. Austin (New York: Paulist Press,1980), 50.

[4] St. Gregory Palamas, The Triads. Trans. Nicholas Gendle (New York: Paulist Press, 1983), 34-5.

[5] Ibn Al’Arabi, The Bezels of Wisdom, 56.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook