Once the order was given at Scetis, ‘Fast this week.’ Now it happened that some brothers came from Egypt to visit Abba Moses and he cooked something for them. Seeing some smoke, the neighbours said to the ministers, ‘Look, Moses has broken the commandment and has cooked something in his cell.’ The ministers said, ‘When he comes, we will speak to him ourselves.’ When the Saturday came, since they knew Abba Moses’ remarkable way of life, the ministers said to him in front of everyone, ‘O Abba Moses, you did not keep the commandment of men, but it was so that you might keep the commandment of God.’[1]

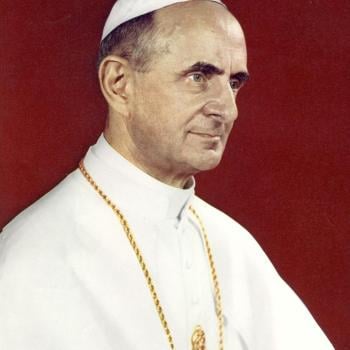

St. Moses the Ethiopian had a rather unusual life; once, he was an escaped slave who turned into a highly effective brigand. Eventually found himself called to the Christian faith and became a monk. Many of his past experiences and the desires which came from them haunted him as he begun his ascetic training; yet, because of the greatness of his spirit, he took the monastic life seriously, properly adorning himself with grace, and he became an extraordinary and important leader in the desert community. While he had once been violent and cruel as an angry brigand trying to survive as an escaped slave, he had become a man of peace, offering and promoting the peace of Christ to all because he had found it for himself.

Moses understood how the laws, rules, disciplines, and practices established, even with the greatest of intentions, can lead to great harm and difficulties for people when they are followed legalistically instead of prudentially. What is worse, many who come in power have no such intention with the rules which they make; what they establish is for their own benefit, helping them not only to keep in power but to attain all the joys which such power offers. After all, the law had designated him to be a slave, and he rebelled against that law, knowing it to be unjust. Once he escaped, he never felt any call to go back and be a slave again, even after he had become a Christian.

Yet, with his prudential wisdom, Moses was not anti-authoritarian. He knew there was a role for authority, for rules and regulations, when they are justly made and justly executed. Such rules should be made for the sake of all, and they should be enforced both for the sake of justice and with great mercy.

Legalism, which looks only to the letter of the law and not its spirit, will never understand the true purpose of the law and so will hurt many people as it enforces the inanest forms of engagement of the law. Legalism, in its desire to follow the letter of the law, will hinder the good being attempted by just laws as it expects and requires only what is said. No matter how skilled the legislator, no matter how well crafted a law is, there will always be a distinction between the letter and the spirit of the law, because the spirit of the law cannot be entirely brought down in words. There is a limit to what can be said; laws try to give general guidance for the sake of the common good, but when dealing with particular situations and needs, the general guidance can and will fail. If we follow the spirit rather than the letter, there will be no problem for us as we adapt to law to fit the circumstances we find ourselves in. Sadly, legalism does not know or allow for such adaptation, and those who are overly focused on the words of the law instead of the spirit behind it will often find themselves opposed to what is better because they demand the mere letter of the law, criticizing and attacking those who do not follow the law to the letter like they do.

We are not given an explanation as to why the monks were told to fast for a week. Likely, it was for the sake of discipline, however it might have been for other reasons, such as a kind of penance for some sin committed in the monastic community. The expectation was considered just. The monks were expected to fast. Moses himself did not oppose the call to fasting, and would have followed it if circumstances did not suggest a greater law, that of hospitality, was to be considered.

When Moses had guests come to his cell, instead of fasting, he cooked a meal for his visitors. Those who were legalistically minded complained that Moses had violated the law. They wanted him reprimanded for what he had done. Who did he think he was to disregard the fast?

Moses knew that the law of charity, the law of hospitality, overruled the call to the fast. If he had visitors, he would rather obey charity, and show his love to his guests, than to disregard them after they made their long and treacherous journey to visit him. Charity, after all, was what led Abraham to have a vision of God at Mamre. Charity and its expectations had to be met above and beyond the discipline being established in the monastic environment. The spirit of the law was to develop disciplines which established well-rounded monks; Moses, through his life and experiences, often with brutal acts of ascetic self-discipline at other times, had already developed the kind of spirit and personality which the fast was meant to achieve. He took the greater route of charity and hospitality over discipline, and the ministers promoted what he had done: the rule of men might be good, but the rule of God had to be followed. Charity overruled the requirements of the fast. It was not that Moses was trying to disengage himself from the monastery and its disciplines: he was living it out in full by obeying the expectations of Scripture and the Christian faith as it regarded hospitality. He met the expectations of being a bishop without being one: “hospitable, a lover of goodness, master of himself, upright, holy, and self-controlled” (Titus 1:8 RSV).

As there is a hierarchy of being, there is a hierarchy of the good, for the good and being are one. We might not be able to properly map out all the virtues, but we do know that the greatest of them is caritas, that is, charity or love. When we find ourselves conflicted with differing virtues or goods, and we cannot do both at the same time, we should heed the lesson of Moses and follow what is greater, even if it means violating some lesser virtue being established by a rightfully-established discipline.

Moses the Ethiopian died holding his peace. As Berbers came into his monastery, they slaughtered everyone who remained, including Moses himself. He did not resist them. He did not fight them. He accepted it as his burden as the consequences of the sins of his past. It was his final trial and temptation, of which he passed; he died confessing Christ, remembered as the big, strong, tall, dark man with a great heart and love for others:

Thou didst abandon the Egypt of passions and fervently ascend the mount of virtues, and didst take Christ’s Cross on thy shoulders.Thou wast glorified in thy works and wast a model for monks, O Moses summit of the Fathers. With them pray unceasingly that we may obtain great mercy (Troparian of the Feast of St. Moses the Ethiopian)

[IMG=St. Moses the Ethiopian by Egy writer [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1975), 139.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook