Dionysius, continuing with his apophatic denials, purifying us from the limitations which would be imposed upon him that come as a result of our conventions, presented a massive challenge to all philosophical and theological inquiry when he wrote that God is not truth. The means by which he established this is two-fold: first, he explained that we cannot touch God with our intellect, and so he reaffirmed the incomprehensible nature of God: neither is Its touch (ἐπαφή) intelligible (νοητὴ). Because we cannot grasp and touch God with our intellect, then knowledge of God as he is in himself is denied to us: neither is It science (ἐπιστήμη). Without any means of obtaining knowledge about God, then there is nothing which we can say about God which can be said to be absolutely true. In this fashion, when Dionysius explained nor [is God the] truth (ἀλήθειά), he denied whatever we assert to be true as comprehending what God actually is.

Dionysius, continuing with his apophatic denials, purifying us from the limitations which would be imposed upon him that come as a result of our conventions, presented a massive challenge to all philosophical and theological inquiry when he wrote that God is not truth. The means by which he established this is two-fold: first, he explained that we cannot touch God with our intellect, and so he reaffirmed the incomprehensible nature of God: neither is Its touch (ἐπαφή) intelligible (νοητὴ). Because we cannot grasp and touch God with our intellect, then knowledge of God as he is in himself is denied to us: neither is It science (ἐπιστήμη). Without any means of obtaining knowledge about God, then there is nothing which we can say about God which can be said to be absolutely true. In this fashion, when Dionysius explained nor [is God the] truth (ἀλήθειά), he denied whatever we assert to be true as comprehending what God actually is.

Dionysius, therefore, began his declaration with the assertion that our intellect cannot grasp God. God transcends all comprehension. He is not a physical substance, so he is incapable of being physically grasped, but he is also not an intellectual substance, so our mind is incapable of grasping after and holding him down. Our intellect cannot circumscribe God: he circumscribes us. He is not an intellectual object: he is the cause and formation of all possible intellectual objects; he establishes them, so that they can be grasped by intellects, while he transcends them as he transcends the intellects themselves.

The more our intellect perceives, the more intelligibles it receives, and the more it knows. As there is no grasping after God as he is in our mind, he transcends all sense of knowledge, for knowledge is found in the accumulation of intelligibles stored in our mind. God transcends our mind and what it can grasp, so he transcends our knowledge. This is why there can no science which can be developed that will let us come to know and comprehend God.

This, then, leads to the declaration that God is not truth. This is speaking in relation to the absolute truth, not the conventional truth of kataphatic theology. Whatever we say, whatever we teach, comes from what we apprehend with our mind, from the intelligibles which we grasp, which we then affirm to be true because we believe that they represent reality. Truth is differentiated from falsehood, indeed, opposed to it; what is wrongly believed is false; what correctly represents and points to the absolute truth we declare to be true. But it is easy to misconstrue what we say to be true to mean it is absolute and not a mere convention. This is the trouble with fundamentalism in theology. It does not understand the distinction between the means by which we talk about God and God himself. This, of course, is a trap which is all too easy for us to fall into, to believe our knowledge and opinions are absolutes. But the absolute is far different from what we can assert. In this way, we must even deny what we say is true as being what God is, because what we say to be true is always going to be on the level of conventional truth, while God is on the level of the absolute. God is not the truth because what we mean by the truth is our apprehension of the truth and whatever that apprehension is, is not God as he is in himself.

St. Albert the Great, explained, with ideas coming out of Augustine, his own way of understanding this difficult declaration in a way which complements what has been said, by saying:

As Augustine says, to touch God with one’s mind is great bliss, but there “touching” means merely reaching the edge of him. “Nor is there knowledge of him” (enabling us to form conclusions about him) or “truth” in the sense in which “truth” is contrasted with falsehood to the facts, truth being an “equivalence between reality and our understanding.”[1]

We can touch God in regards to the way he acts with us. He makes a way for us to touch him so that we be said to be “reaching the edge of him.” that is, in the external representation of himself which he establishes of himself for us. Thus, kataphatic theology represents the truth so long is it properly has the economic revelatory activity of God as its reference and understand that reference leaves out the absolute, transcendent truth which we cannot comprehend. We can establish conventional truths when we truly equate the reality of that experience with our understanding (as long as we do not misunderstand, and therefore, poorly analyze our experience).

It is, likewise, for this reason, there is no contradiction between the assertion that God is truth and God is not truth, even though they appear to be contradictory statements. The first statement is in relation to conventional truth and what we can ascertain of it; the greater our knowledge and understanding, the greater our grasp, and the more in depth our notion and understanding, the subtler such relative truth actually becomes, and with it, God. On the other hand, saying God is not truth is a denial of the convention as being absolute truth; whatever we apprehend to be truth is then not what God is. God is true because whatever we apprehend of the truth, we find God; God is not truth because whatever we apprehend is not God as he is in himself. God is the source and cause of the truth because he establishes the means by which we come to understand the truth and creates the intelligibles in and through his activity with us by which we grasp after the truth and come to some semblance of knowledge of him. Nonetheless, to be true to the truth, we must deny what we ascribe to be the truth as being God if we want to keep away from error and think we can comprehend the absolute in our own limited intellects which can only comprehend relative truth. Anastasius in his scholia, therefore, expounded:

One has said through the metaphor of affirmation that he is the founder and primordial cause of truth, by participation in which every truth whatsoever is true. Now the other has said that through the denial that is of excellence that he is more than truth. For this reason, both “God is truth” is true, since he is the cause of all true things, and “God is not truth” is true, because he overcomes all that is said and thought and is.[2]

What is being denied, then, is the human mind, and the intellectual notions it holds to of God as being absolutely true. Dionysus denied the relative, conventional truth is the same as the absolute, and therefore, that God as he is in his economic revelatory activity, though said to be the cause of the truths which we grasp and allow us to come to know relative truths about God, is less than but still not other than God as he truly is in his immanent nature. We have relative, conventional truth with God, but what we know of the truth will never be what God actually is in his absolute divine transcendent reality. This is true, not only for us, but for all created beings, including those with greater intellectual capability, as Ficino discussed: “For such notions are [merely] intelligible rather than divine and are conceived only in the degree to which they can be captured by our [human] understanding. And as to all the notions that the highest angels have naturally conceived and more sublimely so, they [too] are inferior to God.”[3]

Any created intellect, no matter how great it becomes, no matter how high it is raised, will never be able to comprehend the absolute truth. It will have its grasp of the truth which will be true in regards its relative capability of grasping after the absolute: those with more intellectual potential will be able to hold on and assert greater representations of the truth. But in the end whatever is established in our intellect to be true is not the truth, and so what God is, is not what we ascribe to the truth but something beyond it.

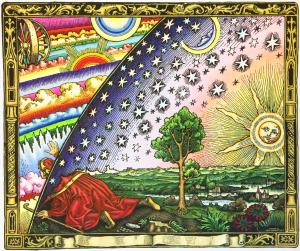

[IMG=Flammarion Engraving colored by Houston Physicist [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons]

[1] St. Albert the Great, “Commentary on Dionysius’ Mystical Theology” in Albert & Thomas, Selected Writings. Trans. Simon Tugwell, OP (New York: Paulist Press, 1988), 197.

[2] A Thirteenth-Century Textbook of Mystical Theology at the University of Paris. trans. L Michael Harrington (Paris: Peeters, 2004), 103-5.

[3] Marsilio Ficino, Mystical Theology in Marsilio Ficino: On Dionysius the Areopagite. Volume I: Mystical Theology and The Divine Names, Part I. trans. And ed. Michael J. B. Allen (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 81.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook