One of the preeminent names for God is “Goodness” or “The Good,” indicating by such an appellation the greatness of God’s providence. “Every good endowment and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change” (James 1:17 RSV). Everything which is good has as its root God’s creative activity behind it; indeed, insofar as they exist, all things are said to be good because they have been created by God. “For everything created by God is good” (1Tim. 4:4a RSV). By his actions, then, we know God is good, for he is the source and foundation of the good itself. “O give thanks to the LORD, for he is good; for his steadfast love endures for ever!” (Ps. 107:1 RSV).

One of the preeminent names for God is “Goodness” or “The Good,” indicating by such an appellation the greatness of God’s providence. “Every good endowment and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change” (James 1:17 RSV). Everything which is good has as its root God’s creative activity behind it; indeed, insofar as they exist, all things are said to be good because they have been created by God. “For everything created by God is good” (1Tim. 4:4a RSV). By his actions, then, we know God is good, for he is the source and foundation of the good itself. “O give thanks to the LORD, for he is good; for his steadfast love endures for ever!” (Ps. 107:1 RSV).

The goodness of creation is a relative goodness, reflecting upon the hierarchy of being itself. The greater the being, the greater the potential, the greater the glory, the greater the beauty, the greater, therefore, the goodness. It is good as a gift of God. It is good insofar as it exists. Insofar as thing fulfills its existence it is good. Nonetheless, this proper good of a contingent being is relative to the absolute good. The finite, contingent goodness of created being is as nothing in comparison to the absolute good, and that absolute good is nothing in relation to the God which established it. As the true source and foundation of the good, God is said to be good, and not only that, God is said to be the only one who properly is said to be good, for all that God does is good. This is, in part, what lays behind Jesus’s words when he said no one is good but God (cf. Mk 10:18).[1] In the absolute sense, God alone is justly said to be good, because God is the one who established the good: God is good according to his actions, and it is a title which properly displays his benevolence. Through the goodness of God’s actions, all things partake of the good. It is following this line of reasoning that Dionysius wrote in The Divine Names:

Be it so then. Let us come to the appellation “Good” already mentioned in our discourse, which the Theologians ascribe pre-eminently and exclusively to the super-Divine Deity, as I conjecture, by calling the supremely Divine Subsistence, Goodness; and because the Good, as essential Good, by Its being, extends Its Goodness to all things that be.[2]

And yet, Dionysius explained, just as we should understand the limitations of human language, so that we know that the name God falls short for the object of our discussion, so the Good, Good, is also to be put aside and negated. Thus, having said neither [is he] Deity, Dionysius in the Mystical Theology continued with his line of thought and said, nor Goodness (ἢ ἀγαθότης). In the Divine Names, Dionysius engaged this negation through transcendence:

The (Names) then, common to the whole Deity, as we have demonstrated from the Oracles, by many instances in the Theological Outlines, are the Super-Good, the Super-God, the Superessential, the Super-Living, the Super-Wise, and whatever else belongs to the superlative abstraction; with which also, all those denoting Cause, the Good, the Beautiful, the Being, the Life-producing, the Wise, and whatever Names are given to the Cause of all Good, from His goodly gifts. But the distinctive Names are the superessential name and property of Father, and Son and Spirit, since no interchange or community in these is in any way introduced. But there is a further distinction, viz., the complete and unaltered existence of Jesus amongst us, and all the mysteries of love towards man actually existing within it.[3]

By indicating God is “supra-Good,” Dionysius has stated that what is said to be good is actually less than what God is. Goodness has all kinds of connotations to it, connotations which when put to God, would imply some limits to who and what God is. Goodness is seen to have evil as an opposition, even if that opposition is from the deficit of the good. If there can be said to be something which opposes the good, even if by its deficiency, then the good can be limited and undermined. God, however, cannot be undermined; there is no possibility of such deficiency within God himself. What is possible with the good is not possible for God. For this reason, God surpasses what is thought of and considered under the category of the good. This was what Anastasius in his scholia meant when he said: “God is said to be ‘goodness,’ but properly, he is not goodness. For ‘wickedness’ is opposed to ‘goodness.’” [4]

Likewise, goodness can easily be misapplied in a substantial form, turning it into something which is then shared by all. For the same reason Dionysius rejected the term “divinity” as being absolutely applicable for God, so then “goodness,” an objective quality which can be predicated upon many and shared by all, cannot be said to be what God is because God is not able to be predicated and shared in such a manner.[5] That is, as Thomas Gallus indicated, Dionysius said “nor goodness, because he is not a quality that can be infused”[6] Goodness is a quality which emerges from God’s creative act; it is a quality which is shared by all who share in being itself. But God, as he is in himself, in his transcendent nature, transcends all that is able to be partaken and infused within us. As we receive his grace through his creative activity, we find ourselves joined to him in relation to grace, not nature; this is because he transcends all concept of nature in himself, so there is no nature for him to share with us. While we become good, thanks to grace, and so join in with what we normally conceive of as the divine nature and so become gods through grace, we must remember that God, the transcendent one, is beyond all we become, including goodness and divinity itself. God, being the source of goodness, transcends it and is not, in the absolute sense, good but beyond it, making him beyond good and evil as there is no opposition possible to him.

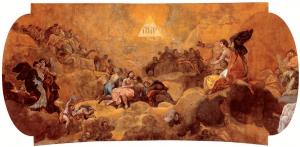

[IMG=Adoration of the Name of God By Francisco Goya [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] A man came to Jesus, calling Jesus good. Jesus responded, asking why the man called him good. Jesus did not deny the goodness, but the attempt of flattery which called Jesus good for the wrong reason.

[2] Dionysius, Divine Names. Trans. James Parker (London: James Parker and Co,, 1897), 32.

[3] Dionysius, Divine Names, 16.

[4] Anastasius in A Thirteenth-Century Textbook of Mystical Theology at the University of Paris. trans. L Michael Harrington (Paris: Peeters, 2004), 105.

[5] See Anastasius in A Thirteenth-Century Textbook of Mystical Theology at the University of Paris,, 105.

[6] Thomas Gallus “Exposicio” in Mystical Theology: The Glosses of Thomas Gallus and the Commentary of Robert Grosseteste on De Mystica Theologia. Trans. and ed. By James McEvoy (Parish: Peeters, 2003), 51.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook