Since the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church has once again made its way into the news, Catholics have felt great shame because of what they have heard has happened within the church. This is a natural reaction of those who desire and seek for what is good. When it is shown that those who should be working for good have been doing evil, there will be grief. There will be confusion. What are we do to about it? It should not be surprising that many will take advantage of our grief and try to exploit the crisis for their own illegitimate ends, such as Bannon’s desire to create his own “independent” tribunals to respond to the crisis: it should be obvious his intention is anything but for the benefit of the church and the support of its historical teachings. [1]

Since the sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church has once again made its way into the news, Catholics have felt great shame because of what they have heard has happened within the church. This is a natural reaction of those who desire and seek for what is good. When it is shown that those who should be working for good have been doing evil, there will be grief. There will be confusion. What are we do to about it? It should not be surprising that many will take advantage of our grief and try to exploit the crisis for their own illegitimate ends, such as Bannon’s desire to create his own “independent” tribunals to respond to the crisis: it should be obvious his intention is anything but for the benefit of the church and the support of its historical teachings. [1]

We have yet to hear the full extent of the crisis. We know how some priests and bishops have either personally abused others, or else, helped cover up and perpetuate the abuse. Not much has been said about the role that others, such as lay workers and even nuns, have had in the crisis. Clearly, the focus is on the clergy for a good reason: those who are in a position of authority have more responsibility, and so more guilt as a response to that responsibility. Nonetheless, we must not neglect the role others have played in the abuse crisis, lest we do not root out all of the problem and the cancer of sexual abuse continues to fester in the church. The whole system needs reform. In a way, Sister Ilio Delio, OSF is right in saying, “The dawning of a new Church is upon us and what form this Church will take in the future depends on the depth of our inner freedom to act in new ways.”[2]

But we must be careful. We must work for structural reforms. As we try to determine what we should do, we must examine how others have dealt with similar crisis, learning from them, both in what good they have done but also in their mistakes, so we can establish reforms which really work. We must be prudent, and not be too quick to execute plans without examining their possible ramifications, determining if they really can help or if they would end up causing more harm than good. That is, we must not employ quick fixes which might seem to help in the short term, but will do little to nothing good (and possibly make the situation worse) in the future. We must especially avoid scapegoating the problem, looking for ways to prop up our ideological desires as the solution to the crisis, because more likely than not, our ideology will be able to change nothing in regards abuse itself. This is true for all sides of the ideological equation. We must not confuse philosophical, political, or theological differences as being the root cause of the abuse crisis, because then we will be fighting an ideological war rather than dealing with the problem at hand. And if we want to confirm thus, all we need to do is examine the world around us, examine people from all walks of the ideological divide, and discern such abuse can be found.

Thus, we must understand the central issue at hand is not gays,[3] nor Vatican II, nor body-soul dualism, but power and its mishandling. Without transparency and independent sources of investigation able to see the abuse, reveal it to the people and civil authorities, abusers will be able to infiltrate the system and use it to their own advantage.[4] This is why those who try to argue their own favored philosophical or theological viewpoint as a cure-all for the sexual abuse crisis have yet to deal with the crisis itself and have rather turned it into a thing of self-promotion. Theological and philosophical concerns must not be ignored, but care must be had and not assume one’s preferred theological tradition is the answer to the crisis and that other systems or beliefs are, in part, to blame for it, as Sister Ilia Delio has done by blaming classical theological notions which she would otherwise like to reject: “In this respect, academic theology is as much to blame for the abuse crisis as the hierarchy itself, insofar as the academy of Catholic theology perpetuates a substance ontology and remains essentially entrenched in ancient philosophies and cosmologies.”[5] Whether or not “substance ontology” and with it “body-soul” dualism is true or false, and whether or not one thinks they should be abandoned for philosophical and theological reasons, suggesting that we must reject them because they are a cause of the abuse crisis is dangerous, because people, if they accept such a conclusion, will set themselves up for another crisis in the future as the scapegoat is slain and nothing substantial has been done to actually reform the church and its institution.

This is not to say theological debates concerning those positions are unimportant, but they should be taken within their own context, instead of using the abuse crisis in order to superimpose a particular ideology as “the solution” scapegoating rival positions as the cause of the crisis. Interesting ideas, such as establishing women cardinals, can be and should be examined in their own right, but we should not think such a change would be a cure-all for the crisis (history shows how women in power can and often are fully capable of abusing the power for their own ends as well). Rejecting the link between the sexual abuse crisis with particular theological visions does not mean such theological questions are meaningless; rather, it is to suggest that they must be kept within their proper domain, engaged with proper discipline, and not over-extended.

Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley is right, then, to say, a clear response is needed by the church. Not only does the church need to listen to the victim of abuse and try to work with them to help them heal from the harm they have suffered, but the church must work to prevent such abuse from happening again using practical means. Praxis is needed more than theoria (theological reflection and contemplation): theoria can be used for all kinds of conflicting practices, which is why focusing on theological questions will not solve the crisis but only overshadow it and allow the crisis to continue. Certainly, we can and should continue to engage the theological enterprise, for we can do more than one thing at a time, and the theological enterprise will help give us the spiritual insight and strength needed to continue to work for reform, but we must not use such theological discussion to subvert us and lead us from doing the work needed for practical reform in the church. The church needs better. It needs people to stop their theological infighting and come together to actually work for reform

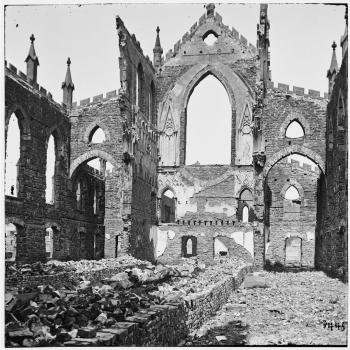

[IMG=nside the former parish church of St Peter, Low Toynton byDave Hitchborne [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Thomas Cromwell used a similar crisis to loot and sack the church under Henry VIII.

[2][2] Ilia Delio, OSF, “Schism or Evolution.” The Omega Center (9-7-2018).

[3] Women have suffered great harm from sexual abuse from clergy within the church, showing how it is not a homosexual problem. Likewise, when clergy have abused young boys and other men, just like in prisons, the reason often is not due to sexual orientation but availability. The desert fathers found that young boys were often a problem within monastic communities, and so established age requirements for the community. Were most monks homosexual? There was no notion of such sexual orientations in the past; what happened is that men, in a confined space, without learning how to deal properly with sexual desires, repressed them instead of working them out and overcoming them; when young boys entered the monastic community and took their place, their homes, in cells with these monks, the urges got the best of the men and they abused the boys who they were expected to guide and protect in the community. If the boys were young girls, the same would have happened, which is why so many stories exist of monks abusing nuns or other young girls have continued to be told and retold through the centuries as a way to shame the whole monastic enterprise.

[4] This is not to say such transparency alone is the solution. But it must be a part of it; for when the darkness of abuse is kept hidden, abusers are able to use the darkness to continue their evil ways.

[5] Ilia Delio, OSF, “Is new life ahead in the church?” Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus (9-6-2018).

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook