God’s potential is fully active and realized in his one simple eternal action. While we can logically understand what this means in abstraction, we cannot truly comprehend it. We live and exist in temporal fashion. We do not know our potential. Slowly, if we strive for it, we hope to realize it. [1]

God’s potential is fully active and realized in his one simple eternal action. While we can logically understand what this means in abstraction, we cannot truly comprehend it. We live and exist in temporal fashion. We do not know our potential. Slowly, if we strive for it, we hope to realize it. [1]

We exist in time, we act in time, and so we find our activities are constantly changing from moment to moment. We do not realize our potential in one unchanging act. We do not realize or understand how it is to be transcendent to time. Likewise, our experience with eternity is temporal; time finds itself circumscribed, and therefore within the domain which eternity rules. We reach out to that which is eternal and get, as it were, a slice of eternity. Each slice comes at eternity from a different angle and so gives us a different result. This is how we experience God’s eternal activity in a temporal fashion, making it seem as if it were a part of time itself. It is not outside of time, because time exists within eternity; this is why we can experience it in time even if the action transcends time itself.

Thus, what exists as one God in God is manifested to us in plurality. We receive it as an unbound infinity, that is, an unbound plurality. Scripture, in talking about God’s actions towards humanity shows how that plurality seems to indicate change. There is no change in the one act of God, but there is a change in our relationship and experience of it. Our temporal experience changes. Our angle of interaction with God changes. It is not God who changes but the direction from which we encounter God is what changes. In this fashion, the one act of God is manifested in time and experienced as a plurality of actions, a plurality of works or energies. The divine energies of Palamas are indeed uncreated as the one eternal act of God is uncreated. They are nonetheless experienced by us in a variety of ways: some temporally, some in their eternity. Grace is uncreated and yet experienced in creation as “created.”

Because God’s potential and actuality are one with his action, it is possible to say God’s action is who he is and not something other than who he is: there is no real distinction between his essence and his existence. This is what allows kataphatic theology to be said to be true, even if what is said in and through it is a conventional truth and not the absolute truth as it is in itself. Likewise, following the conventions where they lead, realizing of course the apophatic restraint which needs to be had over any naming for God, we can say that whatever aspects of God’s eternal activity we experience of God is truly God and not other than God.

Apophaticism reminds us that what we logically divide and establish as qualities are conventions, and not absolutes, and kataphatic theology would remind us this as well as it tells us that all these qualities exist as one in God even as we logically divide them from each other in our theological analysis. In this way, the various energies of God are united together in the one act which is God. They are in reality not other than each other, though for us, they are experienced separately and distinctly because of our inability to comprehend God in his vast infinity as he truly is. We apprehend God in various ways, each way leading to an encounter with God’s eternal act which appears to us in a limited form, one of his energies, allowing us to know something more of God through the qualities we can attribute to those energies. We must be careful, of course; while our experience of God changes, and so it can seem as if God is changing, what is changing is what we apprehend from God based upon the new direction which we use to engage him. God’s eternal act remains always as it is. When it appears God moves from anger and wrath to mercy and forgiveness, the anger, wrath, mercy and forgiveness are all united as one in God’s eternal act with us, but for us, we experience them in relation to our movement towards God.

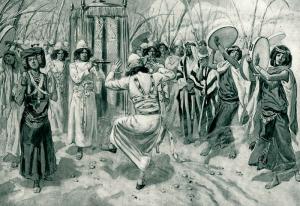

This analysis not only helps us understand better the qualifications implied in our talk about God, but also, our relationship with God realized in theosis. St. Athanasius famously said that: “God became man so that man can become God.” To interpret this correctly, many saintly theologians explained that we become God by grace and not by nature. God gives us the gift of himself to us (and, as the Trinity teaches, this gift of self is Trinitarian and not unitarian, allowing for it to be a gift founded in love). God deifies his creation by his grace. This deification does not turn created being into uncreated being, and so does not make what is not God by nature into what God is by nature. No created thing can simply become one with the uncreated pure act of God: there is no merger or confusion between the uncreated pure act of God and the act of conditioned being. However, conditioned being, by its limited nature, is able to be lifted up and transformed by God, to be deified, to be taken outside of itself, beyond its foundations, as it engages and experiences God. Whatever it apprehends of God, it can take into itself and make one with itself. What it experiences is the energies or actions of God, which truly are God; indeed, which are one the simple act of God. And yet what is able to be apprehended by us is not the fullness of God as he is in himself but God as he economically reveals himself to us and economically engages us mysteriously in his pure eternal act. What we encounter, what we apprehend, we can either cast aside or embrace; when we embrace it, we can make it a part of us. When we do so, it helps us grow. Our being, and with it, our activities, become more like God every time we engage and take into ourselves God’s grace revealed to us in and through his divine energies.[2] We become partakers of the divine nature in this fashion. What we take in and unite with us is not the fullness of the divine nature but something derivative of it which, nonetheless, is not other than the divine nature itself. Grace, mercy, justice, fortitude, knowledge, wisdom, and so many other divine energies join in with us, making us grow in them, becoming godlike in the process, forever sharing in the divine nature in its derived form. Thus, to say we become gods by grace and not by nature, what we mean is that we never merge with the fullness of who and what God is in himself, but yet we partake of God in the derived form of his energies, uniting with them as through reaction with them, as if we are in a continuous, never-ending dance with God.

[IMG=David Dancing by James Tissot (1836-1902), French painter (http://www.gci.org/files/images/jt/TissDanc.jpg) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] Of course, with theosis, we can transcend ourselves, and the potential given to us at our creation. But first, before we transcend it in our union with God, we must achieve the potential already given to us.

[2] As God’s energies are all one and not other from each other, all of them come to us with grace, and can be and must be said to be grace, even as we identify them in and through various other names to indicate the kind of character which is revealed by them.