Dionysius, continuing with his presentation of the transcendence of God, explained neither is It [God] any of non-existing nor of existing things.

Dionysius, continuing with his presentation of the transcendence of God, explained neither is It [God] any of non-existing nor of existing things.

God, in his supreme simplicity, cannot have anything outside of himself predicated to him. Existence is a quality which can be predicated, or not, to those things which have the potential to exist. When existence is predicated to some potential being it becomes an actuality instead of a mere potentiality. This predication is not applicable to God because with God, there is no such possibility of existence or non-existence. St. Albert the Great, interpreting these words, suggested that “’Nor is he anything non-existent’: [means that he is not -HK] anything merely potential.”[1] There is no possibility of mere potentiality without actuality in God. He is above the possibility of non-existence, even as he is above the possibility of existence. Existence comes from it and not something other than him For this reason he is said to be beyond all those things which do not exist but could exist as well as all those things which exist but have the potential not to exist. He is the one who is the source of existence for any given thing. In granting existence, he turns the potential to exist into an actuality. In this way, to be said to be among those whose existence is predicated to them is to be among those who have the potential to have that predication removed from them and so not be. As God grants existence, so, in a way, he can take it away. What is real is, as Anastasius suggested in the scholia, is determined by God: “It – that is, the cause of all things. As it is – just as it is. As realities are – that is, from the fact that they are, but from itself, in a manner over being.”[2]

Existence itself is a quality of being, a realization of a potentiality; what exists has the potential not to be. What is not, but could be, needs existence for it to be. We could, of course, imagine fanciful beings which have self-contradicting characteristics attributed to them which would make their existence impossible given by those self-contradictory characteristics; they are also non-existent, but without the possibility of even being in accordance to those qualities attributed to them. God, likewise, must not be viewed among such impossibilities, but rather, he transcends all possibility, all mere potentiality, all predication of existence as being the source of existence; this is what is meant by kataphatic theology when it calls God a necessary being, with the realization that all his potential is one with his actuality for eternity. He transcends all categories of being, all categories of existence. The order which Dionysius expressed his point in this passage suggests this transcendence: first Dionysius denied God as being among “non-existent things” before denying him as being among those which are existent. If Dionysius first denied existence to God, we could be led to think of him as being inferior to existing things and follow through with a nihilistic assertion that God is among those things which are impossible to be. Such nihilism is always a risk with apophatic theology, which is why care has to be had in discerning the direction of the argument is being made. Apophaticism in theology is about pointing to the transcendence of God, showing how he transcends the categories in question, and so by denying him as being among those who are non-existent, we are led to think he is among those beings with the potential to exist which also exist. But then Dionysius denied this by saying God is not among them, either. God establishes existence, and so transcends it, though we can, in kataphatic theology, say God exists, and this existence is one with his nature, to demonstrate that there is no predication of existence to God.

As God is above all existence, above the realm of being with its many potential gradations, those who find themselves in the realm of being cannot ever comprehend him. This, once again, is asserted by Dionysius in the Mystical Theology when he wrote: nor do things existing know It, as It is. Dionysius is clear in suggesting what is not known is God as he is in himself, that is, God in his absolute transcendent being. Nothing comprehends God; nothing knows the fullness of God. Thus, Dionysius does not deny that we can know God, but he denies the comprehensibility of our knowledge of God. God reveals himself to us, and through such revelation, we come to know God, but God, knowing we cannot comprehend him as he is, reveals himself to us according to our ability to know and understand him. Such revelation is dispensed skillfully by God so that we do not end up ignorant of him; the more revelation we receive, the greater our ability to grasp after the truth, the more we will realize how God transcends anything which we can conceive him to be. He is not an existing thing like the rest of us: he is not capable of being known by us like any other existing thing is. When we observe how difficult it is for us to know and understand the order of being, of which we are apart, and how many within the order of being transcend our ability to comprehend them, we should be able to discern that as the immanent nature of God, God as he is in himself, infinitely transcends that order of being God is infinitely more incomprehensible to us than anything within the order of being. What we see and understand is what God reveals to us; but what lies beyond that revelation is the transcendent light which is so bright, we cannot perceive what lies within it. This is true not only for us, but for all existing things. How can anyone within the order of being, anything which is contingent in being and granted their existence by God, comprehend what lies beyond contingent being? All they can ascertain is through extrapolation. We will never know him as he is but only in an abstract form which only serves as analogy representing the transcendent truth itself. No matter how great the intellect, any created thing will remain limited in relation to the transcendent truth and so will never know it as it is. Or, as St. Albert explained, no existing thing will have a “clearly defined knowledge” of “’what’ it is.’”[3]

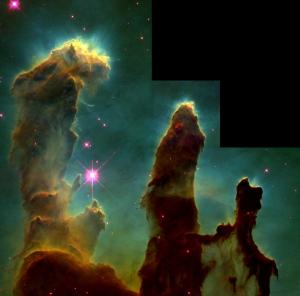

[IMG= Pillars of Creation in the Eagle Nebula by: NASA, Jeff Hester, and Paul Scowen (Arizona State University) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

[1] St. Albert the Great, “Commentary on Dionysius’ Mystical Theology” in Albert & Thomas, Selected Writings. Trans. Simon Tugwell, OP (New York: Paulist Press, 1988), 197.

[2] Anastasius in A Thirteenth-Century Textbook of Mystical Theology at the University of Paris. trans. L Michael Harrington (Paris: Peeters, 2004), 107.

[3] St. Albert the Great, “Commentary on Dionysius’ Mystical Theology” in Albert & Thomas, Selected Writings. Trans. Simon Tugwell, OP (New York: Paulist Press, 1988), 197.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook