“Be angry,” Paul says, “but do not sin; do not let the sun go down on your anger, and give no opportunity to the devil.” (Eph. 4:26-7 RSV). Be angry but do not sin. How can Paul say this if anger is a sin, indeed, one of the deadly sins? How can Jesus cleanse the temple, showing his anger at sin, and not be guilty of sin?

Not all anger is a sin, but the reaction to anger, and specific forms of anger can be sins. Indeed, we must realize this fact: there are many forms of anger. Some are natural, seeking to follow nature and bring things to their proper end, but another is “unnatural,” as it seeks to destroy what is just and right. “Brother, there is anger that is natural, and anger that is against nature.”[1]

That which turns us against the natural good, and that natural good is the source and foundation of justice, leads us to sin. That is anger, when it disrupts our faith, hope and love, leads us away from the charity and justice which we are to have for others. When we act in our anger without regard to justice, we fall into sin. When we act in anger, because of some justice has been overturned, but we overreact, so that we no longer seek for the restoration of justice but vengeance, then anger is a sin. When we are angry about injustice, but preserve charity in our actions, so that we seek after justice mixed with mercy, seeking the restoration of justice without creating new injustices, we find we can be angry but without sin. This is especially true when we think of our own sins, that is, our own acts of injustice. We should be angry at what we have done, seeking to restore the injustice which we displaced before the sun shines on us and reveals our injustices to others.

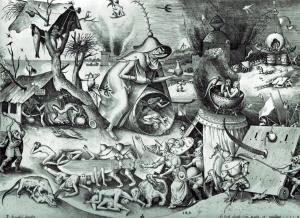

Anger at injustice follows after the pathos of God; but like the pathos of God, that anger must always be slow to reaction, seeking justice mixed with mercy instead of destructive acts of rage. Anger can be said to be one of the deadly sins because it can take our desire for justice and turn it against itself, leading us to act unjustly, becoming the same as those who angered us in the first place. It tempts us to seek a response to injustice which is itself not just, using the excuse of the injustices of others as a way to excuse ourselves.

Anger is a part of the human condition, but we must balance out our anger with charity and justice, using the anger to motivate us, while using our reason to discern the best response to those injustices which have caused us to be angry. Moreover, anger itself can be found at the start of our process for change, but it must be put away, so that we truly let justice take its course. For when we hold on to anger longer than we should, we find ourselves taken over by rage, acting irrationally, and therefore without the wisdom needed to act for the best outcome.

Anger left unchecked turns into malice, and the heart filled with malice will not have the love which is necessary for union with God. This is why, when we can, we should defuse our anger as we seek for justice. Therefore, in a work attributed to St. Antony the Great, we read:

We should not become angry with those who sin, even if what they do Is criminal and deserves punishment. On the contrary, for the sake of justice we ought to correct and, if need be, punish them ourselves or get others to do so. But we should not become angry or excited; for anger acts only in accordance with passion, and not in accordance with good judgment and justice. [2]

We want forgiveness for what we do. Thankfully, God is not malicious with us, but rather, shows his justice mixed with mercy. Therefore, we too should follow God and treat others likewise: “Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you, with all malice, and be kind to one another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ forgave you” (Eph. 4:31-2 RSV). If we want to be forgiven, we must be ready to forgive. What we offer must not be cheap mercy which requires no metanoia, no change, but rather, it is the mercy which allows for such change, and so allows for justice to be done. “Hatred stirs up strife, but love covers all offenses” (Prov. 10:12 RSV). Love is able to heal what has been harmed, but hatred and malice only knows how to destroy. “Curb the impulses of desire by means of self-control, and those of anger with spiritual love. “[3]

The worst form of this malice comes from the pretense of holiness. When malice and anger are mixed with false piety, justice is not only neglected, but becomes itself a victim of the rage. Those who want to be honored as holy, those who want others to fawn upon them for what they say and do, and do not get it, will show forth the shallow nature of their religiosity as they then strike against those who offend them the most. It was concerning this Richard of St. Victor explained:

But even though all malignity is evil, the worst form of this evil is the one that administers its torments under the form of holiness. Often when a person rages against a neighbor because of the vice of anger or venom of envy, an idea forms in his head that he does this because of his zeal for justice. Anyone who has been injured by his neighbor cannot yet easily look at him with an innocent eye. He is displeased with whatever offense he thinks was done by his neighbor. At nearly every moment he accuses him in his private thoughts. Every day innumerable causes flood his mind that prove his neighbor’s guilt, and many reasons come to mind that convinces him that the guilty party must be punished. And often this evil grows in him to the point that he believes that he will be guilty before God unless he corrects his neighbor very severely and reproves his neighbor for his perversity. [4]

This is a problem especially prevalent in today’s society, as we find ourselves more interested in looking at how to correct someone else rather than making sure we act in justice ourselves. Jesus warned us against this when he told us to take away the plank from our own eye, to be angry over our own sins, and not look for and find reasons to be angry at our neighbor. If we look for gossip, if we look for reasons why we think we must judge our neighbor, we have turned away from justice, deceiving ourselves as to the cause and reason for it: we blame our neighbor, when it is our own unsatisfactory life which leads us to act with such irrational furry towards others. Indeed, when we let anger take over, St. Hildegard explains, we no longer even excuse it as being for the sake of justice, but rather because we feel like it is the only way to deal with the hurt which we feel:

[Words of Anger]: I will cast down and trample underfoot anything that hurts me. Why should I be injured? Do whatever you want to do, but do not make me angry. And do not do anything against me. For I will wound you with my sword and I will beat you with my clubs whenever you injure me. [5]

In such rage, without letting any reason control our actions, anger turns us away from God as we center ourselves upon that anger instead of God. It could be justifiable anger, but if we let it lead us without restraint, we will not think upon and contemplate what God would have us do, as our sight will be diverted away from God and towards the object of our wrath.[6] When we have turned away from justice, even when we do so with the pretense of justice, we find ourselves far from salvation, and the more we ignore the injustice established by our rage, the more we will suffer the consequences of injustice ourselves. The more we suffer, the more we will with rage, unless, of course, we put a stop of the cycle and turn it around, seeking to pacify our rage and heal the damage which has been done, not only by others, but by ourselves:

So put away all malice and all guile and insincerity and envy and all slander. Like newborn babes, long for the pure spiritual milk, that by it you may grow up to salvation; for you have tasted the kindness of the Lord. (1Ptr. 2:1-3 RSV).

In our lives, we will find ourselves getting angry. The question we must ask ourselves, what kind of anger do we have, and what do we think we should do with it. That there can be a just anger, and just use of anger, makes its dark twin that much more deadly. This is why many spiritual masters tell us that it is important to learn how to control our anger, even when it is just, so we do not let it take control of us and make us inadvertent practitioners of injustice. It is because anger can lead to such injustice, to the further destruction of justice, under the pretense of justice itself, that it is one of the deadliest sins possible, but only, of course, when it truly is a sin.

[1] Barsanuphius and John, Letters, Volume I. trans. John Chryssavgis (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2006), 251 [ Letter 245].

[2] Attributed to St. Antony the Great, “On the Character of Men and the Virtuous Life,” in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume One. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1983), 340.

[3] St. Thalassios, “On Love, Self-Control and Life in Accordance with the Intellect,” in in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume Two. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1990),310.

[4] Richard of St Victor, “Tractates on Certain Psalms” in Victorine Texts in Translation: Writings on the Spiritual Life. Trans. Christopher B. Evans (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 2014), 164.

[5] St. Hildegard of Bingen, The Book of the Rewards of Life. Trans. Bruce W. Hozeski (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 16.

[6] See St. John Cassian, “On the Eight Vices,” in in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume One. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1983), 83.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook