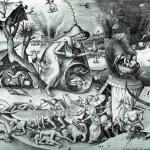

Sin divides and destroys what is good, including and especially the existence of that which is contaminated by sin. It is, as St. Augustine explained, related to death because it seeks for the end of all things, slowly eliminating and destroying them until they are gone:

The highest essence imparts existence to all that exists. That is why it is called essence. Death imparts no actual existence to anything which has died. If it is really dead it has indubitably been reduced to nothingness. For things die only in so far as they have a decreasing part in existence. That can be more briefly put in this way: things die according as they become less. [1]

God is the source of all that is good. He shares that goodness with all things; everything, according to their nature, is good. Creation is good. All things, as they are good, in accordance to that good, should be preserved. What hollows out creation, what defaces it, and turns it against itself, is what must be resisted.

In this way, all things have their foundation in God. So long as we preserve that foundation, our union with God, we can be said to be virtuous. We must not needlessly divide being. Being itself comes from God. It exists from God. It comes from God in its own unity which imitates God. Though creation is not simple like God is simple, its unity mirrors the unity found in God. This unity is meant to be preserved. Sin destroys it. Insofar as sin leads us away from God, it turns us against ourselves, and the very nature of creaturely being. It divides us from God, and as a result, being loses its reflection of the simplicity of God. What was one has become divided into parts, parts which can be and are further divided into more parts, on and on, ad. Infinitum, with each of these parts losing their connection to each other. Being is cut up, and each part of being becomes less and less, as it is further divided more and more as a result of its holistic unity being lost, until each part is infinitely small and next to nothingness itself.[2]

As humanity lost its relationship with God, it lost its relationship with itself. People should come together in a common bond. That bond exists because of the communion human nature had with God. Once communion with God is lost, the bond people have with each other is quickly lost as well. Instead of seeing the whole of humanity as one, we see it is divided into many individuals seeking their own particular desires, warring against each other in order to assert their own individualistic desires. While we might think that we are making ourselves better by self-assertion, we are only setting ourselves up for our own self-destruction. We find the breakdown of being continues within. Our body and soul war with each other; our personality itself slowly finds itself splintered, with our actions holding little to no unifying telos behind them.

It is for this reason that the Desert Father, Isidore of Pelusia, explained the destructive nature of vice as being that which divides humanity from God and from each other, and that virtue confronts vice by returning us to act with a wise simplicity:

He [Isidore of Pelusia] also said, ‘Vices take man away from God and separate them from one another. So we must turn from it quickly and pursue virtue, which leads to God and unites us with another. Now the definition of virtue and philosophy is: simplicity with prudence.’[3]

Divine simplicity does not mean God is comprehensible, but rather, that he is especially one; likewise, humanity, in reflecting the nature of God in themselves, being made in the image and likeness of God, therefore is meant to mirror that simplicity with its own unity. It is one in essence. Sadly, that unity is what was lost to us due to sin. Virtue seeks to restore the simplicity of our nature; it requires, of course, communion with God so that his graces can heal us of the harm done by sin. By reuniting with God, we will find ourselves to restore our proper place, our proper bond, with the rest of humanity.

How, then, are we to live our lives reflecting such communion with God and each other? In prudence: that is, true virtue is not legalistic, but rather, established in and through wisdom. We should act according to the needs of the situation. The spirit shall lead, not the letter of the law. What is needed in one situation, such as a hungry person needing food, will not be the same in another, because a well-fed glutton will not immediately need more food. What is good should be followed. Thus, to act in virtue is to seek after our simple human nature, and then to act according to the natural dictates of that nature according to the particular situations we find ourselves in. This is also why it can be said, without objection, the gravity of sin differs according to the circumstances. St. Basil the Great affirmed this in his preaching:

But, I believe that all who have received this earthly body will not be judged in the same manner by the just Judge since outside influences, which are far different for each of us, causes the judgment in the case of each to vary. For the combination of circumstances not in our power, but involuntary, either makes our sins more grievous, or even lightens them. [4]

We know that the challenges against virtue are many, as the division of being into rival parts can be without end. Nonetheless, the response must always the same: heal what has been damaged, unite what has needlessly be divided, through the best, wisest means possible. We cannot do it all by ourselves, because the greatest divide is the division between God and his fallen creation; it is restored in Christ Jesus as he reconciles all things by uniting heaven and earth in himself. Through that which he has achieved, we can find ourselves united once again with God, and through God, with one another. But if we fight against this, if we try to lift ourselves up to be independent from each other, we risk cutting ourselves once again from God, and then where shall we be?

We must do what we can. Isidore of Pelusia gave us the answer which we need to hear. We must seek unity. “Behold, how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell in unity!” (Ps. 133:1 RSV). This “brotherhood,” this “sisterhood,” this bond of unity is meant to make all of us brothers and sisters as we form one humanity. The true indication of virtue is when we seek this (and not some selfish, individualistic glorification of the self apart from our common humanity). This is what Jesus prayed for before the crucifixion (cf. Jn. 17:22-23). This is what Christ will give to the Father, as all things come together as one when the final enemy, death, the destruction of being itself, is overcome. As long as we seek something other than this, we have a far way to go.

[1] St. Augustine, “Of True Religion,” in Augustine: Earlier Writings. trans. John H. S. Burleigh (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1958). 236.

[2] See St. Augustine, “Of True Religion,” 235.

[3] Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Trans. Benedicta Ward (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1984),98. [Saying 4]

[4] St. Basil the Great, “Homily 11: On Psalm 7” in Saint Basil: Exegetical Homilies. Trans. Agnes Clare Way, CDP (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1963), 172.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook