Plato taught that philosophy serves as preparation for death. Life is impermanent. What comes next relies, in part, on what we have done in life, and philosophy, with its love for wisdom, gives us the guidance which we need in order to have a good death. That is, philosophy prepares us not only to die well, but to be well in our death. Coming to terms with death will help us accept not only death but the process of dying itself. Indeed, it will help us realize that death is always before us and with us. We cannot escape it. The more we try to hide ourselves from it, the worse the process of death and death itself can be for us.

While Plato’s understanding of the afterlife differed radically from Christian eschatology, because Plato accepted a notion of reincarnation, Christians agreed with him in saying that we need to prepare for death. In many ways, Christians saw death and preparing for death to be more important for all of humanity than Plato because Christianity teaches us that death is something which we undergo only once. We have life, and then we shall die. Life is temporal. Death takes us into eternity. But, Christians explained, life and death are intricately connected: what happens in death relates to what we do in life: life is not superfluous, and what we do and achieve in life is integral in the establishment of who we will be in eternity.

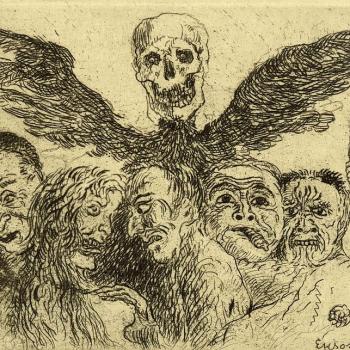

As death takes us away from the good of life, humanity has long seen death as the enemy of life itself. For many, this remains their primary way of understanding death. Even those of us who understand there is potentially something greater which awaits us after death still seek to preserve life as long as we can because life is good. And yet, Christianity tells us that even if death originally served as a curse, brought about as a result of sin, the nature of death has been transformed by Christ. Jesus took on death, the death of all of us, so that he can make it into something good. While death originally led us further away from God, to spiritual death, through Christ it now has the potential of taking us away from the suffering and horrors of temporal existence contaminated by sin. Through death, we can now enter and experience the glory of the kingdom of God. Through Christ’s transformation of death – by death, he conquered the defilement of death from within — we can now be moved to contemplate death and to see the potential good which it can now bring to us once we come to our time to die.

We must not absolutize the good of temporal existence and our current form of physical life: it is good, but it is only a temporary good. It is a part of who and what we are. As we live out our life, we are able to establish ourselves and who we are in eternity. That is what life is for, and why it is good. The error which we must avoid is vitalism, an error which looks at and absolutizes temporal existence, suggesting that we should never allow it end, no matter how torturous prolonging it can cause. Such vitalism keeps us away from our full potential, from the realization of our eternal being. Once we come to understand and accept death, that our temporal mode of existence will come to an end, we can then accept the good which God has established through death itself. Thus, Hans Urs von Balthasar reminded us, vitalism, by having us ignore death, does not allow us to act and be ourselves. Instead of seeking to establish ourselves and to be ourselves, we seek rather to prolong life, ignoring what life is for:

Physical and vital health are not absolutes or ends in themselves. Their value is largely a function of the capacity to accomplish one’s life work as a member of the human community. A person’s central concern, then, should be the best possible performance of his allotted task – even when his physical energies abate, or perhaps largely fail, and he finds it difficult to maintain his vital equilibrium. [1]

In this fashion, Christians are called, even in their lives, to put themselves to the cross, that is, to embrace death, to die to the self and to the world, in order to properly embrace life and live it without delusion. The more we embrace vitalism, the more our existence will become a living hell; the more we embrace the transitory nature of temporal existence, the pilgrimage of life, the more we find ourselves free because the relative goods of temporal existence will not have the power to delude us. We will be able to enjoy them without attachment, understanding and appreciating both their goodness but also their limitations. Then, as Bede Griffiths explained with his wisdom, we can have a good life:

But what happens when we have died to the world, the flesh and the self, when we have seen through the illusion and faced reality? Why then we begin to live to the real world, the real flesh and the real self. This is the paradox which it is so difficult to understand. It is only when you have renounced the world that you can really enjoy the world; it is only when you have renounced the flesh that you can take a pure delight in the flesh; it is only when you have renounced yourself that you can discover your real being. [2]

By accepting death, we can properly live life. By accepting death, we do not reject the good of life, the value of our worldly existence, but rather we understand their limits, allowing us to properly appreciate the good of life itself. By preparing for death, we renounce the world in order to live in it, to accept it for what it is and not attempt to make it for what it is not. We must not gnostically reject temporal existence as if it is valueless. To embrace death, to live life with the acceptance of death, must not be used to disregard our duty to live our life and to live in it well, but rather, it must be used to understand and accept how we act in the world, what we do in the world, will be a part of us and with us in eternity. Death is a change in our state of being, but it is still the same being. The doctrine of the resurrection of the dead teaches us that while we will have the same body in eternity, it will be changed and transformed in its state of being: it will be “spiritualized” instead of merely material in nature. This spiritualized body will transcend the limitations of mere physical existence, and yet it will remain in touch with that which exists within the material realm. The teaching of church about the communion of saints is, in part, a demonstration of this. The saints, though experiencing the glory of heaven, remain in contact with and concerned with those in temporal existence. Henri de Lubac, therefore, showed how Christianity, from its earliest stages, understood this connection, where death was able to be seen as a good allowing us to have far “wider prospects” while remaining in fellowship those living in temporal existence:

The early Christians had a very lively sense of this single fellowship of all individuals, and of the different ages in the course toward the one same salvation. If St. Paul was so filled with joy at the approaching dissolution of his fleshly body that would soon allow him to be united to Christ, it was because this personal feeling of his sprang from a faith that had made it possible by throwing open far wider prospects. [3]

We, too, should look to death, no longer seeing it as a thing of fear, but as something to embrace, as a joy. Obviously, we should not ignore the potential good which we can and should fulfill while we are still alive. For this reason, we should not artificially shorten temporal existence for anyone, including ourselves, but on the other hand, we must not artificially prolong earthly existence, when that potential has been achieved. Though we have long put death to the side, so we do not like to think about it, prepare for it, nor see in it any good, explaining why so many fall for the errors of vitalism, when we realize the pain and suffering which happens when we artificially prolong a life which is ready to be transitioned to the new state of being, we can then accept death and the good which it can bring to the world. It is a delicate balance, to be sure, required for us so that we do not artificially shorten or prolong life, but that balance is entirely lost when we lose sight that death is something to be embraced and accepted because Christ transformed the nature of death. Cardinal Christoph Schönborn, realizing the way Christianity has embraced death as a transition, indeed, as an exodus following Christ into eternity, said that we should no longer treat death with silence, as a kind of taboo which is to be left ignored:

Dying loses its speechlessness when it is not reduced to a biological misfortune but is celebrated as a human event. There is no more eloquent proof of the failure of materialism than its panicked helplessness in the face of death. If death is merely the irreparable final stasis of the machine that is the body, then it is only logical that dying is swept aside into the anonymity of a clinic. [4]

This is not to say there is no horror to death; because, of course, especially for those who of us who have not properly prepared ourselves to face and embrace death, it will come to us all too sudden, when we are not ready. Likewise, it will be terrible for many of us because it will be apocalyptic in nature: when we die, we find who we are and what we have made of ourselves revealed to us (a realization established in and through the particular judgment). “The dangers of the transition are the same as the dangers of life. Life is revealed in dying, and this is why the ars bene moriendi consists in the ars bene vivdendi.” [5] If we have not embraced death in life, and so lived life in the face of death, we will have to face that which we have ignored, and that can be horrifying. But even that horror can and will come to an end; the revelation will be great and shocking, but it is never the end: it is only the beginning. Accordingly, Sergius Bulgakov wrote, we will move beyond that shock and into what comes after, the resurrection of the dead:

The face of earthly life is turned toward death. Death is an object of horror, about which people try to forget; terrible is the hour of death and the “preliminary judgment.” But despite this and above this, death is a joyous hour of initiation or new revelation, of the fulfillment of the “desire to be delivered and to be with Christ,” of communion with the spiritual world. In practical terms, death, as what awaits us on the immediate horizon, blocks for us what is more distant: the resurrection to come, which seems abstract compared with the immediate concreteness of death. But in the afterlife, all this has changed, for the prospect of death and its revelation no longer menaces us: Death has come and its revelation has been accomplished. The place of death is taken by universal resurrection, which naturally becomes an object of fear and trembling for some and joyous hope for others, while for many, if not the majority, it becomes an object of fear and hope at the same time.[6]

We prepare for death by preparing for what comes after death. We live well in order to die well. Life and death are intricately connected; if we do not live well, we cannot die well. But to live well, we must embrace that life itself has a beginning and an end, and during the time in-between, we can and should develop ourselves, our personal character, so that we can die well. It is because of death we find that life and what we do during it has value. It is because of death we cannot, indeed, must not ignore life and what we can do in it. With a Christian understanding of death, we find ourselves rejecting any gnostic treatment of the world which says the world and all that happens within it is meaningless, while we also reject any notion of existence which reverses such a gnostic error by thinking there is nothing to be gained in the transition of death. Death is not our end; it is only the end of the beginning.

[1] Hans Urs von Balthasar, “Health Between Science and Wisdom” in Explorations in Theology V: Man Is Created. Trans. Adrian Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2014), 111.

[2] Bede Griffiths, Return to the Center (Springfield, IL: Templegate, 1977), 91-2.

[3] Henri de Lubac, Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man. Trans. Lancelot Sheppard and Elizabeth Englund, OCD (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 119-20.

[4] Christoph Schönborn, From Death to Life. Trans. Brian McNeil, CRV (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1995), 180.

[5] Christoph Schönborn, From Death to Life, 185.

[6] Sergius Bulgakov, Bride of the Lamb. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 375.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!