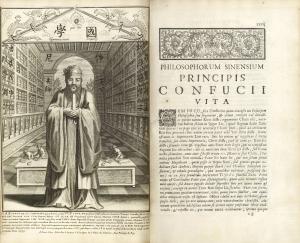

When the Jesuits began their mission to China, they had to find a way to engage the Chinese. Matteo (Matthew) Ricci came to the conclusion that he had to come to the Chinese embracing their cultural heritage, looking to and accepting what could be demonstrated as a natural theological truth. Initially, he and his fellow Jesuits entered China, shaved their heads, acting like Buddhist monks, but that did not bring much success; it was when they studied the classical Confucian tradition that they discerned a new way to engage Chinese thought, and so they promoted an engagement with Confucian thought, taking what they thought was acceptable within Confucianism and using it as a way to discuss and point to the Christian faith. This meant they had to be creative, looking broadly to what they thought was acceptable, allowing converts to continue to follow many Confucian traditions, such as ancestor veneration, so long as those traditions were given an orthodox understanding.

While Ricci’s Jesuit superiors, as well as many Chinese converts to Christianity, found Ricci’s accommodations to Confucian thought not only permissible, but successful, others criticized Ricci and the Jesuits, claiming they accepted superstitious, if not idolatrous, pagan traditions.[1] This was the theological heart of the “Chinese Rites Controversy,” as explained by D.E. Mungello:

The presentation of this accommodating interpretation of Confucianism became entangled with the previously discussed struggle among European Christians called the Chinese Rites Controversy. The most important rites involved were rituals performed in honor of ancestors and Confucius. Some missionaries claimed that these rites involved worship of Confucius and ancestral spirits as idols. While conceding that certain rites to ancestors were superstitious, the Jesuits argued that the rites to ancestors had an essential social and moral significance. They did not violate the monotheistic nature of the Christina God because, the Jesuits said – though other Christians disagreed – the Chinese were not praying to their ancestors for benefits form beyond the grave. [2]

Sadly, not just for the Jesuits but for Christians in China, Ricci’s position quickly became unfavorable in the Vatican, though in the 20th century, the Vatican would change its position and accept the framework which Ricci tried to establish:

The Chinese Rites Controversy involved many people and much bitterness. Eventually the Jesuits, who were the leading proponents of accommodation, lost this battle. As a result, the Jesuit interpretation of Confucianism was discredited, and accommodation was rejected by Catholic authorities in Rome in 1704, a rejection that was later confirmed by papal decrees of 1715 and 1742. (Much later, in 1939, this rejection was reversed by Rome on the grounds that similar Japanese Shinto rites were more civil and social than religious in nature). [3]

It is difficult to determine the full impact of this in-fighting. Chinese officials liked Ricci and his approach, accepting missionaries who followed it, while rejecting others who did not. While it might seem that Ricci’s approach was revolutionary, and that is why it took the Vatican centuries to recognize its value, this was not really the case. It followed traditional Catholic engagement with pagan philosophy, taking in and accepting what could be learned from it. The Catholic tradition had long accepted the notion that Christians can and should embrace the truth wherever it is to be found, and to use it in missionary endeavors. Thus, as Henri de Lubac wrote, “When Ricci treated Confucius as Ambrose treated Seneca or Cyril Plato, he was on the right path….”[4] Ricci and the Jesuits were on the right path; certainly, there were aspects of their thought which could be and should be modified and improved, not because their method was wrong, but because greater engagement with Chinese thought should create revisions as Chinese thought is better understood.

What was new with Ricci was the culture which he sought to engage. China, with its history, and sophisticated cultural heritage, brought many European assumptions to question. That challenge was something many Europeans did not like. But it cannot be stressed enough: what Ricci did was follow what Europe had learned during the renaissance. It is easy to see how Ricci continued a line of thought which can be found with great men like Marsilio Ficino, Cardinal Bessarion, and Agostino Steuco. Like them, he discerned the seeds of truth as it spread itself into the world. And, as already indicated, after centuries of reflection, the Vatican came to approve the strategy and accept what was promoted by Ricci, as can seen in the words of Pope Pius XII:

This is the reason why the Catholic Church has neither scorned nor rejected the pagan philosophies. Instead, after freeing them from error and all contamination she has perfected and completed them by Christian revelation. So likewise the Church has graciously made her own the native art and culture which in some countries is so highly developed. She has carefully encouraged them and has brought them to a point of aesthetic perfection that of themselves they probably would never have attained. By no means has she repressed native customs and traditions but has given them a certain religious significance; she has even transformed their feast days and made them serve to commemorate the martyrs and to celebrate mysteries of the faith.[5]

Sadly, this came too late for Christian missions in China. The damage had been done. But this understanding and strategy remains with the church as can be seen in the way the church is wanting to engage the needs of the peoples living around the Amazon. Thus, as Junno Esteves pointed out in Crux, Cardinal Perdo Barreto Jimeno of Huancayo sees the up-coming synod in the Amazon as trying to deal with and embrace the needs of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon region:

The objective of the upcoming Synod of Bishops for the Amazon is to highlight the need for religious, political and social leaders to come together and defend the dignity of indigenous men, women and children and an ecosystem that is crucial to the environment, said Peruvian Cardinal Pedro Barreto Jimeno of Huancayo.[6]

Many critics of the up-coming Synod, like those who reacted against the Jesuits during the Chinese Rites controversy, have tried to indicate that the synod will be promoting heresy because of its engagement with the indigenous peoples. The Editors at the National Catholic Register, ignoring the church’s tradition and teaching concerning inculturation, suggest there is something illicit in the approach, calling it a “distortion”:

And, with the formal release of the synod’s instrumentum laboris (working document), the issue of married priests was indeed present as a potential problem, alongside other areas of concern, such as the document’s treatment of ecological issues and its distortions of inculturation. [7]

Because the synod could alter the discipline and practices for those in the Amazon region, according to their needs, this has likewise been said to go contrary to Christ, who, the Editors at the National Catholic Register, strangely said the church can never allow for exceptions become a norm: “So, for the welfare of the Church and for the salvation of the souls that have been entrusted to its care by Jesus, exceptions can never become the rule, at the upcoming Pan-Amazon synod — or anywhere else.”[8] Can they not see that in the history of Christianity, let alone with Christ himself, exceptions often became the foundation for new norms? Christ consistently found himself criticized for the various “exceptions” he established to the Law of Moses (exceptions only in the sense that they ran contrary to a particular spirit and interpretation his opponents held). The development of the sacrament of confession demonstrates another example of an exception slowly became the norm, because originally, such confession was rare and for only serious sins, but the development of spiritual direction in monastic communities established the exception which began to promote more frequent confession, until it was seen as normative to have frequent confession. Likewise, the rise of the priesthood separate from the bishopric came out of extreme need, as bishops could not visit all the parishes within their jurisdiction, so the priests took over liturgical duties in those areas that the bishop could not frequent. More and more examples could easily be brought forward (such as issues of clerical celibacy to rules surrounding matrimony), but what is important is to realize that the church can and does develop its disciplines, often establishing exceptions which form the foundation for a new development, and this is not something contrary to the church but a part of how the Holy Spirit works with it. Thus, Sacrosanctum Concilium explains, the church does not want to impose artificial sterility through the imposition of “rigid uniformity in matters which do not implicate the faith”:

Even in the liturgy, the Church has no wish to impose a rigid uniformity in matters which do not implicate the faith or the good of the whole community; rather does she respect and foster the genius and talents of the various races and peoples. Anything in these peoples’ way of life which is not indissolubly bound up with superstition and error she studies with sympathy and, if possible, preserves intact. Sometimes in fact she admits such things into the liturgy itself, so long as they harmonize with its true and authentic spirit.

Provisions shall also be made, when revising the liturgical books, for legitimate variations and adaptations to different groups, regions, and peoples, especially in mission lands, provided that the substantial unity of the Roman rite is preserved; and this should be borne in mind when drawing up the rites and devising rubrics.[9]

Those who would challenge the synod because it seeks to adapt to the needs of the indigenous people challenge, if not outright reject, the church’s official teaching and missionary practice:

Religious institutes, working to plant the Church, and thoroughly Imbued with mystic treasures with which the Church’s religious tradition is adorned, should strive to give expression to them and to hand them on, according to the nature and the genius of each nation. Let them reflect attentively on how Christian religious life might be able to assimilate the ascetic and contemplative traditions, whose seeds were sometimes planted by God in ancient cultures already prior to the preaching of the Gospel.[10]

Matteo Ricci understood this; and the early success he had with the Chinese demonstrated what could have been a long and fruitful Chinese-Christian engagement if it were not subverted by his fellow Catholics. Those who attacked the Jesuits, suggesting they were accepting superstitious rites because they accepted positive natural theology where it could be found in accord with the Christian tradition, were shown to be wrong by the Vatican. Sadly, their heirs are with us, and they are the ones condemning the church’s desire to promote such an engagement with the indigenous peoples in the Amazon region as promoting a “neo-pagan agenda.” Just as the critics of Ricci were wrong, so they are wrong now:

The Catholic Church rejects nothing that is true and holy in these religions. She regards with sincere reverence those ways of conduct and of life, those precepts and teachings which, though differing in many aspects from the ones she holds and sets forth, nonetheless often reflect a ray of that Truth which enlightens all men.[11]

Likewise, the church, as St. John Paul II understood, accepts many levels of divine revelation in the world, with one being the “book of nature”:

This is to recognize as a first stage of divine Revelation the marvellous “book of nature”, which, when read with the proper tools of human reason, can lead to knowledge of the Creator. If human beings with their intelligence fail to recognize God as Creator of all, it is not because they lack the means to do so, but because their free will and their sinfulness place an impediment in the way.[12]

Allan of Lille, in the medieval era, like many of his contemporaries, said the same when he said, “Everything in the created universe is like a book for us, a picture, a mirror, a truthful sign of our life, our destiny, or condition, our death.”[13] The church is capable of recognizing natural revelation, and with it, natural theology: Ricci embraced this with his engagement with the Chinese, Augustine embraced it with his engagement with the Platonists and other philosophers, and Paul himself embraced it on Mars Hill. There should be no problem for Christians to look at the indigenous people and learn from them what they have received from their own engagement with the book of nature, to see how it can and does point to the fullness of the truth in Christ. This is not about the “deification of nature,” as some have suggested, even as it was not the deification of nature when other Christians, throughout the ages, have promoted similar understanding of how nature serves as a form of revelation to us.

Thus, far from representing an aberration, the Amazon Synod demonstrates the church engaging its own teachings, its own understanding of how Christians should engage the peoples and cultures of the world. Critics, trying to undermine the church in its mission, are the ones who have ignored tradition and threaten to subvert the church with their own ideologies. Hopefully, their criticism will be ignored and we will not see a repeat in the Amazon region what happened to China.

[1] Another, more credible, criticism was that Ricci only reached out to the elite in Chinese society. Confucianism might speak to scholars and those with political authority, but the ordinary people, the poor and downtrodden, often were left out from such considerations. While this was often raised by some Franciscan missionaries who engaged other parts of China than where Ricci and the Jesuits found themselves, it sadly did not go far enough and propose alternative forms of inculturation, because if it did, then they would have taken the best of Ricci’s ideas and brought to them a needful corrective.

[2] D. E. Mungello, The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500 – 1800. Second Edition. (New York: Lowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 83.

[3] D. E. Mungello, The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500 – 1800, 84.

[4] Henri de Lubac, Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man. Trans. Lancelot C. Sheppard and Elizabeth Englund, OCD (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1988), 290.

[5] Pope Pius XII, Evangelii praecones. Vatican translation. ¶58.

[6] Junno Arocho Esteves , “Synod Emphasizes Church’s Mission To Defend The Vulnerable, Cardinal Says,” in Crux (7-18-2019)

[7] The Editors, “Memo to the Pan-Amazon Synod: The Gospel of Christ Doesn’t Preach Exceptions” in National Catholic Register (6-28-2019).

[8] The Editors, “Memo to the Pan-Amazon Synod: The Gospel of Christ Doesn’t Preach Exceptions.”

[9] Sacrosanctum concilium. Vatican translation. ¶37-8.

[10] Vatican II. Ad Gentes. Vatican translation. ¶18.

[11] Nosta Aetate. Vatican translation. ¶2.

[12] St. John Paul II, Fide et Ratio. Vatican translation. ¶19.

[13] Allan of Lille, “The Book of Creation” in Literary Works. Trans. Winthrop Wetherbee (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013), 545.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!