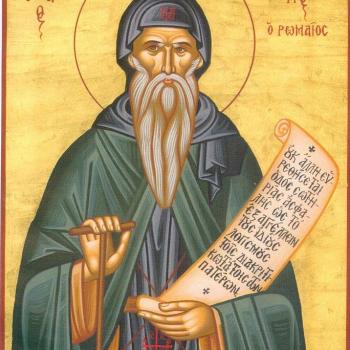

While the value of authentic religious sentiments raises people up so that they are caring people who better others as they better themselves, others like to appear good and holy because of the power and authority they think they gain from such appearances. Many of them become religious zealots, not because they truly believe, but for what they think they can gain; such people try to impose upon God their own expectations, revealing a blasphemous intent to control God instead of listening to him and discerning the greater mystery of love which he would like to reveal to them. Century after century, there are those who appear very religious, very proper, but this is all for show. They try to justify themselves with others by making up rules and ideologies which place them and their own desires into the center of all things. In doing so, they end up shaming true, faithful followers of God. We can see this in the friends of Job who tied to find some reason to shame Job, but we can also see this in the way the parents of the Theotokos, Mary, suffered humiliation from their peers, because until Mary was born, their marriage was a childless marriage.

The way God works with the world in history often serves to reveal and overcome the pretenses of those who claim to speak on his behalf. The people of Israel believed children were a blessing, and a couple who were childless was cursed by God. Barren women were often treated with scorn. And yet, God lifted up a good and faithful couple, Sts. Joachim and Anne, by giving them the greatest gift possible in their older age: Mary, who represented in herself the perfection of Israel, and with it, the height of humanity in relation to God. Through lowly, indeed, disgraced parents (in the eyes of the so-called faithful), God did what he normally did: overturned the presumptions of the arrogant and proud and established his glory in the midst of those who others considered to be the least and most unworthy in the eyes of humanity. God’s preferential option for the poor is not just a preferential option for the materially poor (but he stands by and promotes them), but also for those who are unjustly outcast and derided by society.

Sts. Joachim and Anne could never have expected what was to come about through their holy union; their humility and holy love opened up the pathways for the birth of the Theotokos, and through the Theotokos, for the incarnation of God. God had been preparing humanity through the people of Israel so that he could establish his place on earth, to walk among us, to be one of us. The grief they had experienced turned to joy when they were granted such a holy child; this, St. Gregory Palamas explained, allowed them to represent the way God was about to overcome the grief which humanity suffered as a result of its sin through the coming of Christ:

Why did she come from a barren womb? In order to put an end to her parents’ sorrow, transform their disgrace, and prefigure the deliverance from the grief and curse of the forefathers of the human race, which was to come about through her.[1]

Barren humanity was to be barren no more: the time was close at hand, as Mary, the Mother of God, was born. The grace which God gave to St. Anne, the grace which allowed her to give birth to Mary, sanctified Mary in the womb. “We believe that she was sanctified from her mother’s womb. If Jeremiah and John were sanctified before they were born, why not Mary?[2]’ In Anne, God finished his preparatory work among humanity: Mary was conceived full of grace, with a perfection that had been lost until that time, so that in and through her, he would have the proper place for his own birth among humanity.

No one has ascended into heaven but he who descended from heaven, the Son of man. And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life. For God sent the Son into the world, not to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved through him (Jn. 3:13-17 RSV).

God’s work with humanity has always been to draw humanity back to him, to raise it up so that it can be saved. God descended, that is, became incarnate and become man, but as he descended from heaven, he helped lift up humanity, so that it would be fitting for him to be the God-man. The birth of the Mother of God, the Birth of Mary, was like the beginning of a new day, the dawn in which the sun of righteousness could then rise up and shine across the world. Nonetheless, we must keep in mind that her glory was a human glory; she was raised to human perfection, even as she was filled with the Holy Spirit, so that she could properly fulfill her role in the drama of salvation. Sergius Bulgakov, reflecting upon this, wrote:

The extraordinary outpouring of the gifts of the Holy Spirit, unique in its type, at the moment of the Most Holy Virgin’s conception, in her conception and in her birth, was a divine supplying for human infirmity. It was, first of all, because of the obvious righteousness and holiness of “the ancestors of God” Joachim and Anne, and of the whole God-pleasing series of their forbears; the holiness of birth corresponds to the holiness of the parents. Secondly, it was because of the holiness of the Most Pure Virgin herself, shown even before her earthly birth in her pre-temporal and pre-worldly self-determination. And however much it is possible to speak about “the immaculate conception” and nativity of the Most Pure and Unblemished One, even here grace does not automatically or mechanically select for itself an object that remains passive in this election; rather it responds to the counter-movement of human nature itself. The Mother of God acquires freedom from personal sinfulness, preserving it in her nature the whole power of natural sin and its infirmity. [3]

The grace which was given to Mary, given to her at her conception when she was filled with the Holy Spirit, was something she cooperated with throughout her life, so that it grew as she grew. She could have closed herself off from it. She still had her freedom. But in that freedom, she had the opportunity to grow in grace, and that is what she did, showing to us the growth which is possible for us. Grace must never be as something which forces itself upon us, turning us into mere objects which it controls, rather it frees us, and so Mary with the greatest grace had the greatest freedom.

Sts. Joachim and Anne, the great and holy parents of Mary, had a great and loving married life. They longed to have children, but they continued to follow God and live a holy life despite the way others thought of them. They were to represent, more than those who had a great number of children, the beauty and grace possible with the married life (and not the sham so many put forward because they try to live out a lie by having many children to overcome sorrows and grief they experience in a rather unhappy married state). They had only one child, but in that one child, the glory of true love is revealed, the bounty of marriage is shown, as “… the Mother of God, this newly established world higher than the world, appeared today as the fruit of married life.”[4] Marriage is more than just having children, and those who have no children can have as graced a marriage as those with many; the fruit of marriage is found in the grace God gives to the couple, grace which must be cooperated with through acts of love for it to grow. Sts. Joachim and Anne were already holy, with a great marriage, even before the birth of Mary, but with her birth, God lifted them up and showed to the world his way was different than those who often spoke in his name. Those who often seem unwanted, those who are outcast, those who zealots often ignore, are the ones God works with; he lifts up the lowly to overcome the spiritual deceit of the proud.

[1] St. Gregory Palamas, “On the Birth of the Mother of God” in Saint Gregory Palamas: The Homilies. trans. Christopher Veniamin and the Monastery of St. John the Baptist Essex, England (Waymart, PA: Mount Thabor Publishing, 2009), 335-6.

[2] Achard of Saint Victor, “The Nativity of Blessed Mary” in Achard of Saint Victor: Works. Trans. Hugh Feiss, OSB (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 2001), 184.

[3] Sergius Bulgakov, The Burning Bush. Trans. Thomas Allan Smith (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2009), 63.

[4] St. Gregory Palamas, “On the Birth of the Mother of God” in Saint Gregory Palamas: The Homilies. trans. Christopher Veniamin and the Monastery of St. John the Baptist Essex, England (Waymart, PA: Mount Thabor Publishing, 2009), 337.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!