While holiness, which includes moral and spiritual purity, is important, we must never assume the qualifications we make concerning moral and spiritual purity properly represents such holiness. We often get things wrong. One of the ways we do so is assume holiness is something individualistic, something which we achieve all by ourselves. While some might agree, this is wrong, because it tends towards the Pelagian heresy, they still tend to be individualistic, as they ignore the community aspect of holiness. To become holy, we need others, even as we need God and God’s grace. We cannot become holy if we completely detach ourselves from the rest of world. When we try, we fall for pride, the kind which is related to the fall of humanity, a pride which helps sin further cut up and divide humanity. Christ wants us to realize our unity, to understand we are interdependent with each other, that our humanity is communal, which is why one of the things Christ does is work to restore our lost unity by incorporating us into his body, making us one with each other through himself.

Even when we try to separate ourselves from everyone else, especially those we deem to be impure, we cannot do so; no matter how much we try, we still find ourselves connected to the world around us and the people in it. The unity which we lost is always there; what we create through our sin are walls of division, walls which can be and will be taken down.

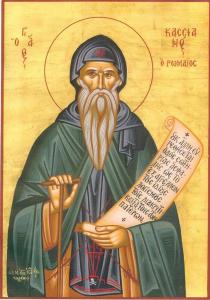

We are meant to love and respect the dignity of each other, even those who we find to be impure in some fashion or another. The pursuit of purity, when it comes out of a pursuit of a purity which we create through our own ideologies (such as racial purity), a purity which would like us to have no contact with anyone we deem impure so as not to be stained by such contact, is a temptation which we must constantly fight throughout our lives. This was something which St. John Cassian learned through his discussion with Abba Daniel, and as such, something he thought important to write down so his readers can likewise learn this same lesson:

That the pride attached to this purity is more pernicious than any other crime and shameful deed and that on its account we would acquire no reward for our chastity, however integral, those powers that we mentioned before are the witnesses. Since they are believed to have no fleshly tinglings of this kind, they were cast down into perpetual ruin from that sublime and heavenly position on account of a prideful heart alone. [1]

When we seek an individualized purity, we end of denigrating the people around us, always finding something about them which we deem unacceptable. Not only do we find ourselves led by the sin of pride, that pride makes us quite uncharitable, and, due to such uncharity, far from the holiness which we claim for ourselves. That is, the more we look down upon others, and view them as so impure contact with them will defile us, making us impure, the more we will treat them with contempt and malice, making us the one who is impure. We end up imitating the downfall of Satan, who in his pride, became malicious against the rest of creation, unable to recognize or accept its goodness.

If we look at Jesus, how shows us what true purity, true holiness, is like; the one who is holy, the one who is pure from such holiness, is full of love, loving everyone, including those who they might consider to be impure, seeking to help and liberate them from all oppression (physical and spiritual), including and especially their sins. Thus, such love would not have us ignore injustice, rather, such it will have us acknowledge when injustices are being done, and seek to overturn them, sometimes by undermining the causes of those injustices, and sometimes by bearing the burdens of such injustices upon ourselves.

Because, if we want to be holy, we will be loving, holiness will always prove to be communal, because we will need to have relationships with others that reflect such love. Similarly, holiness is a thing of grace, which is why we must have a relationship with God, through which, we find ourselves receiving God’s sanctifying grace. When we understand holiness is communal, and a thing of grace, we will better understand why we should not be judgmental, finding excuses to deny our connection not only with the rest of humanity (who we deem to be impure for one reason or another), but also with those who, like us, have found a place in the body of Christ (the church):

And there is a further turn to this. When I reluctantly continue to share the church’s communion with someone whose moral judgments I deeply disagree with, I do so in knowledge that for both of us part of the cost is that we have to sacrifice a straightforward confidence in our ‘purity,’ Being in the Body means that we are touched by another’s commitments and thus by one another’s failures. [2]

Being connected to others, finding ourselves tied with each other so that we share, in some way, with the faults of each other, does not mean we must accept those failures, letting them remain uncorrected. We must, with compassion, and prudence, do what we can to help people overcome their faults, even as, sometimes, we must accept, we will have to help them do so, bearing the blunt of their burdens on ourselves. We must also accept that that there might be people who we cannot help much, because they are not (and, during their temporal existence, might not ever be ready) to change. We should still love them, though if they are causing problems to us, or others, we might have to engage them with a just mercy, such as when those who threaten to harm others might need to be stopped and rendered harmless (such as through a kind of incarceration which still looks after and seeks to help them change for the better).

As Christ took on the whole of humanity, indeed, the whole of creation, and all the defilement and impurity found in it, Christians who find themselves becoming a part of his body should find themselves doing likewise. The more we find ourselves drawn to Christ, receptive of his grace, the more we will find ourselves becoming like him, sharing in his work on the cross. We will find ourselves bearing more and more of the burden of others. Christos Yannaras pointed out that this was something many monks and nuns came to realize in their own spiritual practice:

For the monks, this act of taking on another’s guilt, voluntarily and without protest, was not simply an opportunity to increase in humility. It was a practical manifestation of their conviction that sin is common to all, an obvious way of participating in the common cross of the Church, in the fall and failure of all mankind. The monk is “apart from all” but also “joined with all,” and sees the sins of others as his own, as sins common to the human nature in which we all partake.[3]

While monks and nuns are able to do this in a special way, those of us not called to the religious life should find our own way to incorporate Christ’s work on the cross into our own lives as well. We must learn to overcome our spiritual pride and the kind of judgment it would have us make against others. Now, again, this is not meant to say we should deny the need to promote reform, especially if and when we find grave abuses coming from within the church, but it points out, we should do so with grace, helping to root out, the best we can, the causes of such injustices, helping, likewise, those who we would otherwise judge impure become holy instead of casting them aside, waiting for them to be damned for eternity. For, by being joined to the body of Christ, by having the name of Christian put on us, we are to find ourselves becoming more and more like him, in whatever walk of life we are called to serve.

[1] John Cassian, The Conferences. Trans. Boniface Ramsey, OP (New York: Newman Press, 1997), 165. [Fourth Conference; Abba Daniel].

[2] Rowan Williams, “Making Moral Decisions” in The Cambridge Companion to Christian Ethics. Ed. Robin Gill (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 11.

[3] Christos Yannaras, The Freedom of Morality. Trans. Elizabeth Briere (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1984), 69.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.