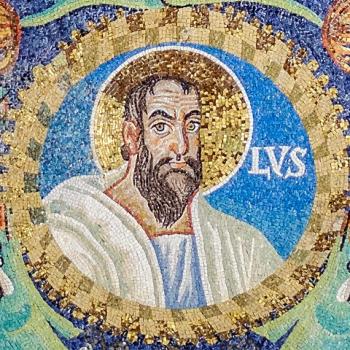

Since the missionary work of St. Paul, Christianity has had a rather ambiguous relationship with paganism. Paul was universal in his thought and application, willing to work with and engage pagan a variety of traditions because he understood they contained elements of truth in them. This was one of the reasons why Paul believed that Christianity could and should transcend first century Jewish cultural expectations. Paul’s endeavors allowed people to find their way to God following and adapting their own particular cultural traditions, turning Christianity into a universal religion instead of a mere universalization of a particular culture (first century Judaism), however invaluable that cultural heritage was to the foundation of the Christian faith. Nonetheless, Paul still held great respect and love for his own Jewish background, and he would never have wanted the universalization of the Christian faith to be used as an excuse for any kind of anti-Semitic hostility. Such anti-Semitism, being contrary to the basic teachings of Christ, finds itself far away from the universal approach Paul used to promote the Christian faith.

Perhaps the greatest representation of Paul’s catholic approach to the faith can be found at Mars Hill, where he pointed to the “Unknown God” being worshiped by the Greeks and said it was the same God as the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the God revealed in Jesus Christ. By stating this, Paul affirmed an important point: pagans (Gentiles) and Jews alike had their own particular relationships with God. Of course, Paul understood that there was something special with the people of Israel that God gave them revelation in a way that many others did not possess. Nonetheless, it is important for us to realize that Paul did not think that those outside of the people of Israel were left without providential guidance from God.

Following Paul, the Christian faith opened itself up to and engaged not only Jewish history and theology, but whatever wisdom Christians found in any of the cultures and peoples they engaged throughout the world. It accepted that as Jesus was the expectation of the nations (cf. Gen 49:10). This meant that the wisdom of the various nations could be, and often was, inspired by God. Philosophy, it was said, was given to the Greeks, just as prophecy was given to the Jews. This meant that the various pagan traditions and beliefs should not be viewed merely as some sort of Satanic distraction which must be summarily dismissed. Rather, as God, as the Holy Spirit, was at work throughout the world, various great insights and truths were seeded throughout the world, providing ample fruit for Christians to pick up and take back within the church itself. Thus, the greatest insights and wisdom of the pagan traditions found a home in the church despite their origins.

Nonetheless, it was not easy for Christian to engage pagan wisdom; oftentimes, the results of such engagements were ambiguous in nature. Did they pervert the Christian faith and make it more pagan or did they enhance the faith? This was the risk Christians would have to take, even if many would later question the results of those Christians who did such work. Do we see the work of people who were authentically Christian, or were they pagans adapting themselves to the new Christian milieu? Perhaps the most representative of this incorporation of pagan wisdom into the Christian faith, and subsequent questioning of whether or not the author was authentically Christian, can be found with the person known as Pseudo-Dionysius. Who he is, what he did, and how he influenced Christian theology after him has caused many scholars to suggest different things about him. Some think that he was a Christian who was too enthusiastic for Platonic thought, corrupting Christian theology by adapting Proclus (and other Neoplatonic sources) for his theological presentation. Others have suggested he was actually a pagan who tried to influence the development of the Christian faith when he realized the Christian faith would survive and overcome his favorite pagan tradition. Others, of course, find him to be an authentic Christian witness, who engaged the mysteries of the Christian faith with what he believed was the best philosophical and theological resources he had on hand, resources which likely came from his own pedagogical background. The fact that each of these representations of Dionysius can be made concerning him shows us how ambiguous Dionysius was in his writings.

One of the reasons for the ambiguity comes from the way Dionysius himself wrote. He loved to deal with symbols and analogies and philosophical quandaries. He expected much from his audience, including the knowledge of how to engage his writings. Without that knowledge, without that key, it is easy to create a hermeneutic lens for any kind of reading one wants from him. Another reason for the ambiguity is that Dionysius clearly was influenced from paganism. He could easily be said to be a disciple of Proclus, but he took the pagan element and transferred it into a Christian context. Does the context itself tell us he truly was Christian, or was it merely a cover for his true purpose?

It is clear that some do not want to admit how such an important theologian was so greatly influenced from pagan philosophy (and theology!). Those who want to entirely distance Christian theology from anything pagan have to come face to face with Dionysius. Did Dionysius corrupt the Christian faith? Or did he help reinforce it? That is the question his readers have to discern for themselves. What should not be done is what Tuomo Lankila sees some Christian scholars doing, that is, try to minimize the pagan influence on Dionysius altogether by emphasizing a radical break between Dionysius and his Platonic sources:

We still encounter in scholarship tenacious efforts to minimize the Neoplatonic element in Dionysius. Sometimes the very same doctrines which were earlier thought to depict a radical difference between Dionysius and Proclus are now seen to share common traits, for example, their theories of love.[1]

Thus, we can see some scholars, like William Riordan, recognizing that there is some Platonic influence upon Dionysius, nonetheless emphasize the distinction between Dionysius and his Platonic background.[2] Better scholars, such as Andrew Louth accept the great influence of Proclus and the Neoplatonic tradition on Dionysius. “On the one hand, it is undeniable that many of his concepts are derived from Neoplatonism.” [3] If we are honest with the text, it becomes clear that many of Dionysius’s words and concepts come not from Scripture, but from Platonic dialogues or various pagan oracles. “He is very fond of words from Platonic dialogues or the Chaldean Oracles that one would never expect to find in a Christian, but would regard as commonplace in a pagan philosopher.”[4] We can see this, for example, in the way Dionysius examines the various hierarchies which he believes exists (celestial, ecclesiastical, etc.). W.R. Inge is right in associating this with Proclus:

In the writings of Dionysius we find great prominence given to the notion of a “hierarchy,” a system of grades or ranks in the ladder of being, each of which ministers to the rank below, and aspires to the rank above. This conception is taken from Proclus, not from Plotinus, and is in sympathy with that belief in the agency of angels and demons which characterizes the later Neoplatonism. [5]

Dionysius, employing a Proclean understanding of the universe (with the relationship between the One and the many), establishes a plurality of hierarchies flowing from and participating in the One God. His engagement with the angelic hierarchies come out of this. What Dionysius does is place the angelic orders within the hierarchy of being Proclus established to explain the difference between the One and the various pagan gods, with the difference being the discussion is now about angels rather than gods. This, then, is indicative of the way Dionysius took pagan thought and made it acceptable, indeed, normative, for the Christian faith

To entirely dismiss pagan wisdom would be to dismiss the various truths, the rays of light, found throughout creation, and would then lead Christianity away from rationality and into pure fideism. This is not what Christianity is meant to be. Christianity understands Christ as the cornerstone, as the Truth from which all derivative truths flow. Because he is the cornerstone which holds all such truths up, the Christian faith has a place for them within the church.

But here we find the kind of ambiguity some Christians deride. How will we know what is true or not true, and so what can be incorporated into the Christian faith and what cannot be? In part, the answer of Paul is the one which we need to follow: cultural wisdom can be the foundation for an engagement of the Christian faith. Christian Jews can follow their Jewish traditions and still be Christian, while pagan converts can continue with their own cultural traditions and also be good, orthodox Christians. Paul affirmed both and said the Christian faith in its universality could and should accept diverse cultural traditions by saying he would be all things for all people, a Jew with the Jews, a Gentile with the Gentiles (cf. 1 Cor. 9:20-23). Thus, the writer of the Dionysian corpus represents a Christian engaging his own cultural heritage, which Andrew Louth explains, gives him much in common with other important Christians like Boethius:

What is one to make of this mixture of Christianity and Neoplatonism? Is the Christianity simply a cover for his real conviction which is pagan Neoplatonism? Is he perhaps trying to find within Christianity a place where a now-outlawed Platonism can continue to survive? The long answer to that – for my part – is the rest of this book, which hopes to show that when Deny expounds in his writings is recognizably Christian. The immediate answer, or the beginnings of such, is to not that by the end of the fifth century educated Greek Christians and pagan philosophers had much in common, because they shared a culture. Even in the West in the fifth and sixth centuries, they were educated men whose Christianity was expressed in the clothing of a pagan culture to such an extent that one wonders what their real allegiance was: one things of Sidonius Apollinaris or of Boethius.[6]

To reject an enculturated Christianity is to reject many of the great theologians and philosophers of the Christian tradition. Paul, and therefore Scripture, does not tell us to reject the various cultural heritages found throughout the world, but to embrace them, finding the wisdom they have been given and engage it with our Christian faith. Different people from different cultural backgrounds will offer different forms of engagement with the Christian faith. Those looking from outside those cultures might suggest (as some do with Dionysius), that they see an anti-Christian pagan influence trying to corrupt the Christian faith. This, however, is not an acceptable response. It is a response which the Apostles came to reject as they defended the rights of pagan converts. It was not easy for the Apostles to realize this: it took Paul valiantly standing up for the rights of the converts to have the Council of Jerusalem convened, but once he did, it affirmed the cultural universality of the Christian faith.

The Christian faith is not a legalistic system which expects only one way of engaging the teachings of Christ, but rather, it is a way of life which engages wisdom and finds a way to spread that wisdom throughout the world, incarnating itself in many cultural forms. The Christian faith realizes the nations of the world all seek the truth and all have come to various terms with the truth in their cultural heritages. To those who would think that this is too ambiguous, because it allows for a rich variety of Christian practices which differ from culture to culture, Paul would say they risk the danger of legalism which denounces the spirit and cuts people off from the grace of God.

The Christian faith is a great mystery which goes beyond human wisdom, and so by trying to reduce its proclamation and presentation to one cultural form or another undermines the depth of the mystery itself. Being overly-critical of differing cultural appropriations only demonstrates someone who has yet to truly embrace the mystery of the faith. They show themselves to be stuck in the externals of the faith itself. And is this not a part of the wisdom Dionysius himself wanted us to learn? “However, this divine ray can enlighten us only by being upliftingly concealed in a variety of sacred veils which the Providence of the Father adapts to our nature as human beings.”[7] Thus, Dionysius talks about the sacred veils, the various way providence adapts itself to us according to our humanity, those veils being the symbols which develop in various cultural traditions as a means of pointing to the divine reality itself. These symbols, these veils, remain valid insofar as we find the way to interpret them, seeing how they point to the transcendent truth of the Divine: “We use whatever appropriate symbols we can for the things of God. With these analogies we are raised upward toward the truth of the mind’s vision, a truth which is simple and one. We leave behind us all our notions of the divine. “[8] In this way, God is revealed through the wisdom of humanity but is not tied down or stuck to it. Rather, such human wisdom becomes the initial means by which we slowly elevate ourselves beyond ourselves, until we come directly to the Cause of all, the One who is capable of being expressed in an infinite variety of names and yet no one name at all: “And so it is as the Cause of all and as transcending all, he is rightly nameless and yet has the names of everything that is.”[9] This is true, not only of the way we discuss God in theology, but in the way we engage him in our cultures. He can be engaged in and through all of them – and yet he transcends them and the way we engage him. We can accept the positive value given by them so long as we try not to limit him to any (or all) such expressions; but once we try to limit him in that way, our reification of God ends up creating a false conception of God which can easily lead to idolatry. And this insight is amazingly enough one which tie Platonism with Israel, for both of them agree of the transcendence of the One beyond the expressions and presentations made of the One throughout the ages. “Mind beyond mind, word beyond speech, it is gathered up by no discourse, by no intuition, by no name. It is and it is as no other being is. Cause of all existence, and therefore itself transcending existence, it alone could given an authoritative account of what it really is.”[10] And thus, following Iamblichus, Jews and Christians alike recognize that the only proper representation of God comes from God himself, either through some particular revelation (like the Torah) or some experience of God which helps us know something about him by the way he acts in relation to creation:

For Iamblichus, however, to deny the value of the god’s audible expressions would dismiss the energia of the god, and in principle it would deny the value of the entire sensible cosmos as the energia of the Demiurge. The name of the gods were individual theophanies in the same way that the cosmos was the universal theophany, and since both preceded man’s conceptual understanding Iamblichus says that they should not be changed according to conceptual criteria (DM 259, 1-5) Out of the same respect that Iamblichus had for the cosmos as the sensible expression of the Demiurge, he honored the audible manifestations of the gods.[11]

But if that is the case, once again, this certifies the general notion of Paul in his writing: God is known throughout all the peoples of the world, because each people experience something of the work of God in their history. To reject any particular culture outright would be a way to deny God himself. This is why Christians, when confronting people of other cultures, must engage those cultures instead of dismiss them in their entirety, no matter how ambiguous such an engagement might seem. For in this way, God is truly honored.

[1] Tuomo Lankila, “The Corpus Areopagiticum as a Crypto-Pagan Project,” in: Journal for Late Antique Religion and Culture 5 (2011): 20.

[2] See William Riordan, Divine Light: The Theology of Deny the Areopagite (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2008).

[3] Andrew Louth, Deny the Areopagite (Wilton, CT: Geoffrey Chapman, 1989), 21.

[4] Andrew Louth, Deny the Areopagite,21.

[5] W. R. Inge, “The Permanent Influence of Neoplatonism upon Christianity,” in The American Journal of Theology, Vol. 4, No. 2 (1900):340.

[6] Andrew Louth, Deny the Areopagite, 23.

[7] Pseudo-Dionysius, “The Celestial Hierarchy” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. Trans Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 146.

[8] Pseudo-Dionysius, “The Divine Names” in Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works. Trans Colm Luibheid (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 53.

[9] Pseudo-Dionysius, “The Divine Name,” 56.

[10] Pseudo-Dionysius, “The Divine Names,” 50.

[11] Gregory Shaw, Theurgy and the Soul: The Neoplatonism of Iamblichus. Second Edition (Kettering, OH: Angelico Press, 2014), 204.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!