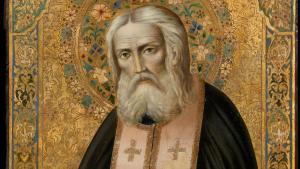

One of the most beloved Russian saints of modern times is St. Seraphim of Sarov. St. John Paul II, in Crossing the Threshold of Hope, connected his holiness to his life of prayer and the state he found himself after his prayer:

Man achieves the fullness of prayer not when he expresses himself, but he lets God be most fully present in prayer. The history of mystical prayer in the East and West attests to this: Saint Francis, Saint Teresa of Avila, Saint John of the Cross, Saint Ignatius of Loyola and , in the East, Saint Serafim of Sarov and many others.” [1]

It might surprise some Catholics and Orthodox that Orthodox saints are often recognized as saints, not just by individual Catholics, but by the Catholic Church as a whole. This is in part because of the agreements made between Rome and various Eastern Catholic churches when they reentered communion with Rome. Those agreements made it clear that Eastern Catholics can continue to promote the saints from their traditions, even if the saints come from a time when they were in schism with Rome.[2] But even without such agreements, this should not be surprising. For, as history shows, many Western saints were divided from the Pope of Rome during the Western schism. While schism is not good, and it hurts all involved, the grace of God is able to transcend the fractures of the church created by humanity and elevate holy men and women despite ecclesial politics.

There is much to love about St. Seraphim of Sarov. He always showed himself to be a man of great joy, even when he faced and experienced events which would have turned many people bitter (once he was terribly beaten up by thieves; his body never fully recovered from that event, and so he is often shown in icons with a crooked back holding the staff which helped him stand up). That joy was seen by those who came to meet him, especially after he opened himself to the public, after the time he lived alone as a hermit, communing with God and engaging the animals he met as his personal friends and companions in his hermitage.

Yet, as a man of ascetic discipline and prayer, St. Seraphim understood ascetic struggles were not the point of the Christian life. To him, the Christian life was simply about the acquisition of the Holy Spirit:

Prayer, fasting, vigil, and all other Christian practices, however good they may be in themselves, do not constitute the aim of our Christian life, although they serve as the indispensable means of reaching this end. The true aim of our Christian life consists in the acquisition of the HOLY SPIRIT OF GOD. As for fasts, and vigils, and prayer, and almsgiving, and every good deed done for Christ’s sake, they are only means of our acquiring the Holy Spirit of God. [3]

What does it mean to acquire the Holy Spirit? Do we not have it when we are baptized and chrismated? We do, but in the same way we experience the eschaton as already there with us and not yet realized in time. We have the Holy Spirit with us thanks to baptism and chrismation. The Holy Spirit provides us grace. It is the gift of God which is given to us from the Father and through the Son. It is the gift of the Kingdom of God. When we are full in the Spirit, that is, when we have fully realized the potential of the gift of the Spirit, we find ourselves experiencing tbeatitude, a never-ending joy which cannot be taken away from us. This is what St. Seraphim was able to come to experience and share with others. Likewise, this is what he meant when he told us that the Christian life is about the acquisition of the Holy Spirit, that is, it is about realizing the gift given to us, turning it from an unconscious grace to a perfectly conscious reality in which all things are experienced and realized through it.

We acquire the Holy Spirit by slowly opening ourselves, through various actions and techniques, to the prompting of the Holy Spirit in our lives. Those techniques help refine us as we slowly change our own internal disposition, a change which affects how we see and experience existence itself. We will come to experience the glory of God, at first temporarily and in part, and eventually continuously and without limits, Prayer is an important part of the process of our realization of the Holy Spirit in our lives because when we pray, we speak about ourselves, our own needs and wants, as well as what little we realize about God, bringing it all to mind and opening ourselves up to the response God gives us. The more we do so with a pure heart full of love, the more we open ourselves to the prompting of the Spirit and find ourselves acquiring the Spirit, realizing it in our lives. Eventually, there will come a time in which such prayer must cease, when we must become silent, so that we can then be lifted up beyond ourselves and truly find ourselves not only embraced by the Spirit, but lifted up beyond ourselves so we become Enlightened by it. Thus, St. Seraphim explained:

But I will tell you in the name of God that not only is it necessary to be dead to them at prayer, but when by the omnipotent power of faith and prayer our Lord God the Holy Spirit condescends to visit us, and comes to us in the plentitude of His unutterable goodness, we must be dead to prayer, too.[4]

Of course, it is possible to consider this next state to also be a kind of prayer, indeed, to be true prayer, if we understand prayer to be communion with God. Thus, when Seraphim talks about prayer, he is only talking about what people conventionally think is prayer, the words and thoughts which are handed over to God. With that in mind, he is telling us that we must overcome that simple understanding of prayer and to do that we must slowly have come to the end of all our thoughts and desires and truly come to the point we are ready and open for the presence of God. But there is more than this. Being dead to prayer is being dead to all thoughts, but also, becoming truly dead to ourselves, so that we find nothing will stand between us from God: union with God will overcome the I-thou duality which we create between us and God as all that we hold to and think of as that “I” will be cast aside and crucified with Christ. This is not to be confused with the death or destruction of our personal existence, but only the elimination of the imputation which we put over that personal existence. Only those who have experienced this, only those who truly have transcended the I-thou duality, can understand this, because the words which we use to describe it come from the duality which is overcome.

To get to this stage, however, requires a pure, loving faith. St. Seraphim understood this, which is why much of his wisdom and advice is for those of us who are beginning our journey toward God, telling us that we must have a living faith which is demonstrated by deeds:

Faith without works is dead ( James 2:26), and the works of faith are: love, peace, long-suffering, mercy, humility, rest from all works (as God Himself rested from His works), bearing of the cross, and life in the Spirit. Only such faith can be considered true. True faith cannot be without works; one who truly believes will unfailing have works as well. [5]

True faith is manifested in love, a love which overcome all sense of dualistic judgments in the world. It is not easy. Love overcomes faults. Love overcomes divisions. The more we acquire the disposition of love, the more we act out on that love, the more we will slowly experience the glory of the kingdom of God, for in the kingdom, that love will be universal:

In the Kingdom of God – the world of men, women and children as planned in the mind and intention of God – people will be so alive, so filled with the eternal life of heaven and the powers of the age to come, that the spirit of friendship, creative energy and joy will be such that it will be difficult for us at present to even imagine it.[6]

This, then, ties to what Jesus told us about rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s:

So they watched him, and sent spies, who pretended to be sincere, that they might take hold of what he said, so as to deliver him up to the authority and jurisdiction of the governor. They asked him, “Teacher, we know that you speak and teach rightly, and show no partiality, but truly teach the way of God. Is it lawful for us to give tribute to Caesar, or not?” But he perceived their craftiness, and said to them, “Show me a coin. Whose likeness and inscription has it?” They said, “Caesar’s.” He said to them, “Then render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” And they were not able in the presence of the people to catch him by what he said; but marveling at his answer they were silent (Lk. 20:20-26 RSV).

Many interpret Jesus’ word dualistically, saying we must split ourselves between earthly glory and the kingdom of God. And, when we are just beginning our spiritual quest, there is some truth to this, insofar as the basic expectations of earthly life, manifested in the dictates of justice, are to be followed, and that is what could be understood as rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s, with Caesar see to represent the dictates of earthly justice. But, once we begin to explore Jesus’ meaning further, we come to understand that there is more depth to his words than this; they tell us to transcend Caesar by giving all that we owe in regards justice to the world. Once we have done this, we will find that what we have left can then be properly given to God. Or, as St. Ambrose told us, we must renounce the world, not by destroying it or negating it, but by fulfilling all our obligations to it so then we can give our whole selves over to God:

And if ye would not be beholden to Caesar, do not possess what belongs to the world. But ye have wealth; ye are beholden to Caesar. If you would owe nothing to an earthly king, leave all that ye have and follow Christ [cf. Saint Mark 20:12; Saint Luke 5:11, 28].And He fittingly decreed first what must be rendered to Caesar [cf. Saint Luke 20:25], for none can belong to the Lord unless he has first renounced the world. But we all renounce in words, we do not renounce in emotion; for when we receive the Sacraments, we renounce the world. [7]

God, Origen pointed out, needs nothing from us. All things, even the things of Caesar, already belong to God. Rather, when we render things to God, it is all about our salvation, that is, about our realization of the kingdom of God. “So, God seeks from us and entreats us, not because he needs something that we have to give to him, but, after we have given it to him, he will credit that very thing to us, for our salvation.”[8] The more we render all things over to God, the more we receive them back, not in the way which we knew them before our experience of God, but as they truly are in God. To render what is God’s to God is to recognize the truth about God and his relationship to the world, to recognize the world and all within it is his. It is for this reason that the best way to render all things to God is to engage love, to act in and out of love, and not just any simple kind of love, nor only a love which goes only to God, but a love which is given out to all in and through our love for God.

This is what the ascetic life is about. This is what St. Seraphim’s hermitage allowed him to experience. We are to realize and experience all things in and through God, and that is because we are to realize and truly experience God in the Holy Spirit. This, then, is what the acquisition of the Holy Spirit is all about: the realization of the kingdom of God. We can experience it in part, and when we do, we should be silent and take in that experience and be enlightened by it, so that we can then apply it and live it out in our lives. But we should seek to acquire the Spirit so it is realized completely, in a never-ending glory, and in that glory, all things will be realized in and through God so that all things will manifest God’s glory. Then, we will find ourselves experiencing a new way of being. This is what St. Seraphim of Sarov wanted us to realize. Let us also follow him and acquire the Spirit, realizing the kingdom of God which is already within us.

[1] St. John Paul II, Crossing the Threshold of Hope. Trans. Jenny McPhee and Martha McPhee (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 18.

[2] Some important Orthodox (Eastern) saints have been officially recognized because of this, including, but not limited to, St. Photius the Great, St. Gregory Palamas, and St. Sergius of Radonezh. Recently, St. Gregory of Narek, an Armenian, was not only recognized by Rome as a saint, but he was elevated to being a Doctor of the Church.

[3] S. Nilus, “The Acquisition of the Holy Spirit” in Little Russian Philokalia. Volume I: St. Seraphim. Ed. and Trans. Seraphim Rose (New Valaam Monastery, Alaska: St. Herman’s Press, 1991), 86. (This is from his famous “Conversation with N.A. Motovilov”).

[4] S. Nilus, “The Acquisition of the Holy Spirit,” 93.

[5] L. Denisov, “The Spiritual Instructions to Laymen and Monks of our Father Among the Saints Saint Seraphim of Sarov,” in Little Russian Philokalia. Volume I: St. Seraphim. Ed. and Trans. Seraphim Rose (New Valaam Monastery, Alaska: St. Herman’s Press, 1991), 27.

[6] Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, St. Seraphim of Sarov: A Spiritual Biography (Blanco, Texas: New Sarov Press, 1994), 493.

[7] St. Ambrose, Exposition of the Holy Gospel According to Saint Luke. Trans. Theodosia Tomkinson (Etna, CA: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 2003), 387.

[8] Origen, Homilies on Luke. Trans. Joseph T. Lienhard, SJ (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1996), 162.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!