In the Byzantine Catholic calendar, the Great Fast, Lent, starts with right after Forgiveness Vespers on the evening of Cheesefare Sunday. It is called Cheesefare Sunday because traditionally it would be the last day the faithful would eat dairy or egg products until Easter (they had already given up meat on the previous Sunday). The focus is not on the fast (though it is a part of what is being contemplated), but the spirit of humility and mercy which is necessary for an authentic Christian life. That is, the central message deals with forgiveness and the spirit of charity which should prevail. We need to realize our own failings and ask forgiveness for all the harm which we have done to others, intentional or not, even as we are to forgive others and show them mercy, so that we can come together in a communion of love.

The Great Fast is about removing all the barriers which stand in between us and God. One of those barriers is our inability to love everyone, including those we believe to be our enemies. It is not that we need to be naive. We should act with prudence. Forgiving someone for the harm that they have done to us, wishing them well, does not mean we have to be with them and work with them and open ourselves to further abuse from them. We must move on. The point is that we must detach bitterness from our hearts, for so long as we hold onto it, the more it will affect us and make us unable to find peace.

Likewise, bringing mercy to the world does not mean we ignore injustice. What we should avoid is a judgmental spirit. That is, we must not use any and all offenses we feel we have received from others, especially minor ones, as excuses for hostility towards them. We must avoid condemning others as a way of making ourselves look great. We should not say things like: “Look at that person over there; look at what they are doing! See how terrible they are! Don’t be like them. Be like me.”

There are many ways the spirit of judgmentalism can manifest itself, among which, those who judge others for what they wear (or do not wear), those who judge others for what they read (or do not read), those who judge others for what they eat (or do not eat), and those who judge others for what liturgical preferences they hold (or do not hold). Paul told us not to be like this; rather, we are to lift each other up, realizing that different people have different needs and different ways of following God:

As for the man who is weak in faith, welcome him, but not for disputes over opinions. One believes he may eat anything, while the weak man eats only vegetables. Let not him who eats despise him who abstains, and let not him who abstains pass judgment on him who eats; for God has welcomed him. Who are you to pass judgment on the servant of another? It is before his own master that he stands or falls. And he will be upheld, for the Master is able to make him stand (Rom. 14:1-4 RSV).

Origen, commenting upon this passage, indicates many ways Christians end up unjustly judging others. Sometimes, he points out, it can be those who are either ignorant or slothful will judge others as scapegoats. Sometimes, those new to the faith and have come to a little knowledge of it will end up thinking they are superior to all and judge others, promoting themselves and their still relatively unformed views with great arrogance:

For, by a perverse arrangement, those who are inexperienced make it their habit to judge those who are experienced, and the lazy judge those who are zealous. But sometimes even those who have received certain initial stages of knowledge become puffed up and exalted over against those who seem to be less capable.[1]

Christianity is a way of life; study of its doctrines, by itself, will not help us. We need to live out the faith, treating others in the way we would like to be treated. We know that we make mistakes every day. We are imperfect. We would not like it if people judged and condemned us for all our minor faults. So why do put others down for theirs? We must reject judgmentalism, we must avoid the desire to condemn others, and rather, find a way to mediate Christ’s grace by showing his merciful forgiveness to all.

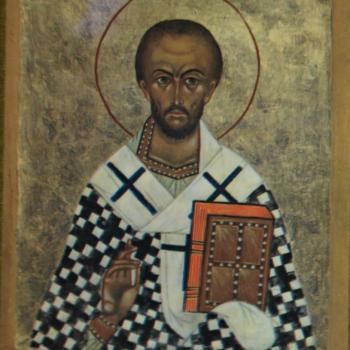

Thus, before the Great Fast, we are told to focus on the spirit of mercy. We are reminded of our own failings in the past year. We are encouraged to forgive others as we ask everyone around us to forgive us for what we have done. We want forgiveness for ourselves. If we are unwilling to show it to others, we risk cutting ourselves off from grace and not receiving the forgiveness and mercy which we long for. Jesus made it clear, “For if you forgive men their trespasses, your heavenly Father also will forgive you; but if you do not forgive men their trespasses, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses” (Matt. 6:14-15 RSV). St. John Chrysostom, explaining this, warns us that if we do not live with a spirit of mercy but rather hold onto a judgmental spirit, we establish the foundations by which we will be judged:

So that the beginning is of us, and we ourselves have control over the judgment that is to be passed upon us. For in order that no one, even of the senseless, might have any complaint to make, either great or small, when brought to judgment; on you, who art to give account, He causes the sentence to depend; and “in whatever way you have judged for yourself, in the same,” says He, “do I also judge you.” And if you forgive your fellow servant, you shall obtain the same favor from me; though indeed the one be not equal to the other. For you forgive in your need, but God, having need of none: thou, your fellow slave; God, His slave: thou liable to unnumbered charges; God, being without sin. But yet even thus does He show forth His lovingkindness towards man.[2]

What judgment we render unto others will be rendered back to us. When we are judgmental, when we are not merciful but condemnatory, we create our own condemnation. The judgment which we receive will come in part from the way we treat others. Whatever hate we hold onto will come back at us. It is our hate, it is our lack of mercy, which we will face in that judgment. God is merciful and all-loving; he is willing to forgive us and elevate us with his grace. But we hold back such mercy and grace from ourselves if we hold onto unlove and the judgment which it renders against others. Then, without such mercy, all we will have is the judgment to come when we face Jesus.

Judgmentalism is a work of darkness. It is bitter, unjustly cynical, and seeks to destroy. The works of darkness turn us away from charity and grace, and the more we hold onto them, the further we find ourselves from God. Likewise, the more we hold onto them, the further we cut ourselves from others and the common good. And the further we are from the common good, the further we will be from the good itself, the good which we need for beatitude. In this way, it can be said we make our own punishment. The time of the eschatological judgment is the time in which we come face to face with ourselves and what we have made for ourselves. Those who have not cast off the works of darkness will face the darkness they have established:

Besides this you know what hour it is, how it is full time now for you to wake from sleep. For salvation is nearer to us now than when we first believed; the night is far gone, the day is at hand. Let us then cast off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; let us conduct ourselves becomingly as in the day, not in reveling and drunkenness, not in debauchery and licentiousness, not in quarreling and jealousy. But put on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make no provision for the flesh, to gratify its desires (Rom. 13:11-14 RSV)

In the Great Fast, we should not just be concerned about what we eat or do not eat, but rather, about what is in our heart. We must fast from the darkness and put on Christ. And what does Christ show us when we turn toward him? That the way forward is the way of mercy and grace, the way of love. We should not put on a show, making ourselves look better than others by emphasizing what we are doing; rather, we should focus on doing what is right and good without care or concern of what others know or do not know of what we do:

And when you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces that their fasting may be seen by men. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward. But when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, that your fasting may not be seen by men but by your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you (Matt. 16:16-18 RSV).

What is important is not the external appearance, nor the fast itself, but the goal of the fast, which is to let ourselves be transformed, to become more Christ-like. We should strive to come out of the Great Fast as better persons than we were before it began. Whatever form of fasting we follow should help us overcome a self-centered, selfish way of life (which is at the forefront of all judgmentalism); it should open us up to receive the presence of God wherever we are so that we can be nourished by the Word of the Lord, the Word of Truth, the Word of Love. Fasting for the sake of fasting will just leave us hungry; fasting to show off to others our apparent superiority over them will only leave us with ephemeral accolades. And so, St. Hilary of Poitiers points out, we must seek to be adorned with beautiful works:

He teaches us that the benefit of fasting is gained without the outward display of a weakened body, and that we should not curry the favor of the pagans by a display of deprivation. Instead, every instance of fasting should have the beauty of a holy exercise. For oil is the fruit of mercy according to the heavenly and prophetic word. Our head, that is, the rational part of our life, should be adorned with beautiful works because all understanding is in the head. [3]

During the Great Fast, then, we must remember the point of our fasting. It is not the fasting itself. It is about acquiring treasures in heaven. But this must be understood, not gnostically, but eschatologically, recognizing that heaven and earth come together and are one in Christ. We are to look for the realization of heaven in our lives, to receive and participate in the eschatological kingdom not merely after we die, but now. We truly can receive the blessings of God, the treasures of heaven; we can be transformed by grace and see the beginnings of our deification in our present lives. This is true only if we seek after grace and follow the path Christ established to receive them, the path of mercy and grace, the path of love. Fasting helps us overcome inordinate passions and desires which reinforce selfish egotism. And it is this selfish egotism which we must eliminate. This is why it is good to start out the Fast with an engagement of humility and love. We need to admit our failings to others. We need to forgive everyone around us, showing them our love. The two practices go together.

Judgmentalism reinforces the egotistical self as it seeks to use others as scapegoats, hoping that by their suffering and condemnation, it can avoid its own demise. But we cannot let it gain such control over us. To truly experience the kingdom of God, to experience the eschatological union of heaven and earth, the false self which we have developed must die; all the barriers we put between ourselves and God (and others) must come down. The Great Fast helps us take it all down, but only if we let it.

[1] Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans. Books 6 -10. Trans. Thomas P. Scheck (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2002), 236.

[2] St. John Chrysostom, “Homilies on the Gospel of St. Matthew” in NPNF1(10): 136. [Homily XIX]

[3] St. Hilary of Poitiers, Commentary on St. Matthew. Trans. D.H. Williams (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 2012), 75.

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!