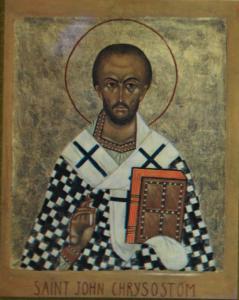

On the feast of St. John Chrysostom, it is important to remember the reasons why he was recognized as a saint, but also to keep in mind the things which he did wrong and not ignore them. He was, like many in his time, struggling to understand the implications of his faith as it is put in practice; he could, and often would, speak on social justice issues, criticize the powers that be. Many times, he preached to comfort Christians who were struggling with their faith. He was not liked by many who sought power for themselves, as he was seen as getting in their way, and so they had to find a way to orchestrate his own downfall (leading to his banishment, and excommunication). But, he also was a man of his times, and he embraced many of the prejudices and biases of his time, giving them support, indeed, justifying them, making them worse for centuries to come, as can be seen in his treatment of the Jews. While it can be argued that the Jews were not his real target in many of his sermons where he brings them up, but Christians who engaged Jewish practices which Chrysostom thought they should not, his strategy was to make the Jews and their traditions look terrible, and in doing so, he ended up creating many black legends about the Jews, legends which would be used by Christians to not only further engage anti-Semitic rhetoric, but the outright discrimination, abuse, and killing of the Jews. We should look back with horror when we see such rhetoric, and the actions which followed, and when we do so, we are right to criticize Chrysostom’s contributions, but in doing so, it is also imperative we understand why he was viewed as holy, to see the good which he not only promoted, but did, and to see how, sometimes, the good which he promoted could be and should be used to criticize him and the bad which he did. He was, like so many of us, a complicated, indeed, conflicted man, and like many of us, he could be and would be saved despite the wrong he said and did; we should not sanitize our saints, even the great ones, because when we see the good with the bad, we get a better understanding why grace is necessary, why we can’t, by ourselves, work out our salvation. When we whitewash the saints, we undermine one of the many lessons we can and should learn from them – we should learn from their mistakes, and what they did wrong, so we don’t repeat the mistakes of the past, even as we should look to the good which they did, discern why it is good, and work to engage a similar good in our lives as well.

For Chrysostom, perhaps one of the best messages we get, beyond notions of social justice, is that Christianity should truly be the religion of mercy, looking for and giving mercy to everyone who seeks it out (we can only wish that he acted this out in his relationships with the Jews and Gentiles). His Paschal homily demonstrates the best of his spirit, the best of his promotion of mercy, and so, the best message which we can get from him: Christ’s resurrection from the dead is for the good of all, no matter who anyone is and what they have done in their lives. It is this spirt which seems to be behind his social justice message. Everyone needs Christ’s help, and no one, no sin, is outside of the domain of grace. Father George Maloney gives us a good glimpse of what this meant for Chrysostom:

St. John Chrysostom rebelled against rigorism and the teaching that the three capital sins – apostasy, homicide and adultery – could be forgiven only once after baptism. In his voluminous writings, Chrysostom rejected the graded system of penance and insisted that the value of penance had to be judged by the inner dispositions of the penitent. For the ordinary good Christian there were other ways of receiving God’s reconciliation, such as confession, contrition, humility, almsgiving, prayer, and the forgiveness of others. With Chrysostom, no capital sin lies outside the present mercy of the Lord, and no limit is assigned to how often a sinner might be reconciled.[1]

Chrysostom knew that what Christ did for his love for humanity, his love for creation, showed us his strength, when he emptied himself of all his power and glory in the incarnation in order to accommodate himself for us. The more he lowered himself for our sake, the weaker he appeared to be, in reality, the greater he proved himself to be:

He knew full well that condescension and accommodation in no way could lessen his glory. For his glory was not alien to him or brought in from outside himself; it was not given to him by robbery; it was not another’s glory which did not belong to him. Christ’s glory was truly and genuinely his by nature.[2]

Chrysostom pointed out Christ knew us and our weakness, that is, Christ knew how difficult his teaching could be for us, which is why he was willing to engage us, not in accordance to his divine authority, imposing himself upon us, but engaging us where we were at, in ways which best helped us understand what he wanted as well as offering us the aid we need to follow him:

If he were not willing and ready to accommodate himself, it would be useless to teach sublime doctrines to those who would not listen or turn their attention to them. As it is, even if it were of no benefit to them, yet it did instruct us, it did prepare us to have a suitable conception of him, and it did persuade us that he changed to a more lowly mode of discourse because these people could not yet accept the lofty and sublime things he was saying. Therefore, when you see that he is saying lowly and humble things, do not think this is a mark of any meanness in his essence. See it is an accommodation and condescension on his part because the understanding of his hearers was weak.[3]

Christ’s great mercy, Christ’s great love for us, Christ’s accommodation for us, is best represented by his death. There, in Christ’s kenosis, his accommodation was complete. Christ’s kenosis is shown to be one with his glory, demonstrated to us through his resurrection from the dead. Having accommodated himself to us through such self-emptying love, Christ has let loose a great bounty of grace into the world, a grace which can and will help heal the world from the ravages of sin. Having gone to the limit of creation in his self-kenosis, nothing is outside of domain of Christ’s saving grace. Christ welcomed sinners, he dined with them, he showed them his love, contrary to what the rigorists of his day expected or desired from the messiah. He even used the criticism some gave of him as a way to engage everyone, as an opportunity to show how great the heart of God is:

Now the tax collectors and sinners were all drawing near to hear him. And the Pharisees and the scribes murmured, saying, “This man receives sinners and eats with them.”

So he told them this parable: “What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the wilderness, and go after the one which is lost, until he finds it? And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing. And when he comes home, he calls together his friends and his neighbors, saying to them, `Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep which was lost.’ Just so, I tell you, there will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance (Lk. 15:1-10 RSV).

At his best, Chrysostom followed this spirit, welcoming those who were being criticized and questioned, even to the point of finding himself attacked and criticized for doing so (as can be seen in his conflict with Theophilus of Alexandria, when he showed hospitality and helped the “Tall Brothers” when they came to him, monks Theophilus accused of committing many crimes, as well as being heretics for their support of Origen; this was what eventually led to Chrysostom’s downfall, that is, to his judgment and condemnation at the Synod of the Oak). At his worst, he exemplified the same judgmental spirit which condemned Jesus, which we see in his speeches against the Jews. He was not perfect, far from it, but at his best, he contributed much to the Christian message, much which has been lost over time, while the worst of what he said and did, sadly, was what was picked up by Christendom and used to further harm the Jews. We can and should honor and praise him for the good, helping to promote the best spirit of his writings, without denying the evil he said and done, working to correct him and those who followed him in such bad actions.

[1] George A. Maloney, SJ, Your Sins Are Forgiven: Rediscovering the Sacrament of Reconciliation (New York: Alba House, 1994), 58-9.

[2] St. John Chrysostom, On the Incomprehensible Nature of God. Trans. Paul W. Harkins (Washington, DC: CUA Press, 1982), 265 [Homily 10].

[3] St. John Chrysostom, On the Incomprehensible Nature of God. 196 [Homily 7].

Stay in touch! Like A Little Bit of Nothing on Facebook.

If you liked what you read, please consider sharing it with your friends and family!

N.B.: While I read comments to moderate them, I rarely respond to them. If I don’t respond to your comment directly, don’t assume I am unthankful for it. I appreciate it. But I want readers to feel free to ask questions, and hopefully, dialogue with each other. I have shared what I wanted to say, though some responses will get a brief reply by me, or, if I find it interesting and something I can engage fully, as the foundation for another post. I have had many posts inspired or improved upon thanks to my readers.